Skin Cancer Rates Have Australians Running for Cover

Under a blazing afternoon sun, Simon Roebuck cuts an elegant figure as he gracefully rides his board down a foaming wave to the crowded sandy beach. Other surfers wait for their own perfect waves.

It is a picture-postcard scene of tropical Queensland, Australia’s fast-growing “Sunshine State,” in a popular beach set between the “Sunshine City” of Cairns and the “Sunshine Coast” north of Brisbane.

Except for one thing: Many on the beach are fully clothed, with long pants, floppy sleeves and broad hats. Nor is Roebuck an Aussie image of a sun-bronzed surfer. He is pale. Pink, in fact.

“Skin cancer, mate,” the 21-year-old printer explains as he smears high-test sunscreen on his face. “Everybody’s worried about it now.”

A startling shift in attitude and behavior is under way Down Under, and for good reason. Medical experts say two out of three Australians will get skin cancer, including potentially fatal melanomas. Here in northern Queensland, doctors say four out of five residents will develop skin cancer. And the melanoma rate is the highest in the world.

“We’re the skin cancer capital of the world,” said Sue Devine of the Queensland Cancer Fund.

She added: “One thousand Australians will die this year from skin cancer. It’s really tragic. Because they’re not just dying of skin cancer. They’re dying of ignorance as well.”

But Australia’s response may present a useful lesson as summer starts for millions of Americans. One in six Americans will suffer from skin cancer, and the rate is increasing nearly 4% a year, according to the National Cancer Institute. Nearly 7,000 Americans will die from melanomas, the most serious form of the disease.

Because of the growing threat, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has asked sunscreen manufacturers to mark lotions with warnings of overexposure to the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays. Here, the warnings are far more urgent and obvious.

With more than 300 cloudless days a year, Queensland TV and radio stations issue “burn time” warnings, including when the sun is most dangerous--usually from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.--as a key part of daily weather reports.

A barrage of broadcast ads and billboards hammer home a campaign to “Slip! Slop! Slap!” As a character called Sid the Sea Gull invariably explains, that means slip on a shirt, slop on some sunscreen and slap on a hat.

The most common sunscreen is SPF 15, which provides 15 times the protection of bare skin. It’s available in family-sized half-gallon jugs in many shops, along with tightly knit cotton shirts, umbrellas and French Legionnaire-style hats with neck flaps and broad visors. Surprisingly, much of the beach clothing is dark.

“We try to promote not wearing white,” explained Anna Voloschenko, education director of the Queensland Cancer Fund in Brisbane, the state capital. “Because white reflects the ultraviolet rays right onto your face.”

Since the worst skin damage happens to those under 18 years of age, cancer fund officials visit schools, starting in kindergarten, to warn children about playing in the sun without protection.

As a result, some schools now enforce a “no hat, no play” policy that requires children to wear hats on the playground. At least one school requires sunglasses as well.

“I’d like to see swimming competitions and sports played at night,” said Ann Burnell, the deputy mayor of Townsville.

The city recently drew more than 200 entries from around Australia for a contest to design “sun-safe” clothing. The winning entry included sleeves that extend down over the hands. The designer makes no apologies.

“It’s like Russian roulette if you ignore the sun,” said Janet Catchpole, 37, who lives on the Sunshine Coast. “I had skin cancers removed from my face because I was so exposed to sun when I was in school. People in their mid-30s should not have bits of their face removed.”

Less severe “sun-safe” clothes are worn at Townsville’s Cranbrook Primary School. Until two years ago, the 900 students wore traditional V-necked shirts and skimpy shorts called “bumhuggers.” Now, many wear long sleeves, dark shirts, long shorts and knee socks.

“The attitude has changed a great deal,” said Mary Barry, a mother of six who designed the new uniform. “Initially there was quite a lot of skepticism and even antagonism. It’s a very entrenched lifestyle here. Like California. For sun worshipers, the browner the skin, the healthier the person.”

Not anymore. The reported incidence of melanomas in Queensland has more than doubled among men and gone up by 50% among women over the last seven years, according to Dr. Bob MacLennan, an epidemiologist at the Queensland Institute of Medical Research.

“We think it reflects sun exposure of 20 to 30 years ago,” he said.

As in America, only one in 20 skin cancers are malignant melanomas, which spread quickly and can be fatal. Far more common are basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas. They are less lethal but still dangerous if not treated in time.

Basal cell cancers usually appear as small, fleshy bumps, while squamous cell cancers appear as red, scaly patches. Surgery is usually minor but can be disfiguring.

Doctors say several factors appear to account for skin cancer rates here. Just north of the Tropic of Capricorn, northern Queensland is one of the world’s few tropical regions heavily populated by Caucasians. It is on the same latitude as Zimbabwe and Haiti.

A high percentage of residents are of British or Celtic descent, and thus light-skinned and sensitive to the sun’s harmful rays. Many work outside on cane farms or fishing boats. And over the last few decades, many have basked on beaches in ever tinier bathing suits.

“In Mexico, they have a siesta in the middle of the day,” said Devine, the cancer fund official. “In the Middle East, they wear long robes. Here we go to the beach and put on tanning oil to turn brown.”

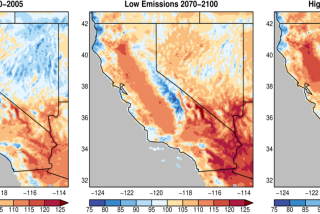

No one knows the effect, if any, of depletion of the ozone layer, which blocks much of the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. Scientists believe a “hole” in the ozone over Antarctica has led to increased exposure of ultraviolet radiation in parts of the Southern Hemisphere, including Australia.

For now, the changes are slow but steady. A recent survey found Australian fashion magazines using fewer tanned models. Cosmopolitan Sydney now boasts an upscale “Anti-Skin Cancer Shoppe.” But as with AIDS and smoking, people don’t necessarily change behavior just because it’s risky.

Ask Simon Roebuck. The perpetually pale surfer says his older sister still basks on the beach each weekend.

“She wants a tan,” he said with a shrug. “I keep telling her she’ll be sorry.”

More to Read

More to Read

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.