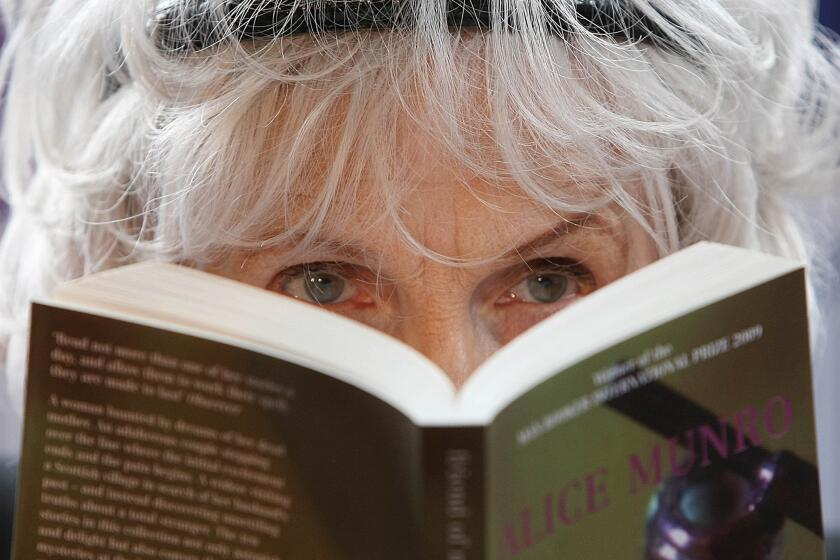

The Bible of Middle America : THEIRS WAS THE KINGDOM: The Uncondensed Story of the Reader’s Digest and its Founders, DeWitt and Lila Acheson Wallace, <i> By John Heidenry (W. W. Norton: $29.95; 640 pp.)</i>

The recent announcement that Reader’s Digest was laying off 10% of its U.S. work force was well-timed--though this was certainly not the company’s intent--to buttress the accuracy of John Heidenry’s massively detailed history of the magazine, which argues in its final chapters that after the deaths in 1981 and ’84 of DeWitt and Lila Acheson Wallace the current management “wasted no time in turning the RDA (Readers’s Digest Assn.) into the exact opposite of what its founder wanted it to be--into a company that put profit firmly first.”

DeWitt Wallace, who created the Digest in 1922 from his handwritten condensation of magazine articles he found in the New York Public Library’s periodicals room, would have been horrified by chairman George Grune’s explanation that the layoffs were necessary “to be certain we will meet our growth targets for fiscal 1994 and beyond.”

Wally, as everyone at the Digest’s Pleasantville, N.Y., headquarters called him, was always more interested in using the magazine to promote the American way of life than in generating profit; in later years he and his wife Lila (who is a colorful but decidedly secondary character in this account) made large donations to nonprofit organizations ranging from the Metropolitan Museum to Outward Bound. The childless couple bequeathed their billion-dollar baby to 11 charities.

A job at Reader’s Digest in its heyday was considered a cushy sinecure by publishing insiders. Editors were paid high salaries to perform not terribly arduous duties; condensing a single article could take days. To be sure, Wally’s paternalism had its creepy aspects--ask any RDA wife or female employee browbeaten into modeling their outfits in humiliating mock fashion shows during parties at the Wallaces’ High Winds estate--and he fired quite a few executives over the years. But the wholesale layoff of employees for financial reasons ran completely counter to his vision of the RDA as one big happy family. When a 1973 lawsuit charged the Digest with sex discrimination, he responded in bewilderment, “But we love our girls!”

That kind of willed blindness was typical of Reader’s Digest from the beginning. Although he is scathingly critical of current RDA management, Heidenry, co-founder of the “St. Louis Review,” does not fall into the trap of romanticizing those who carefully nurtured the blend of inspirational self-improvement articles, earthy humor and right-wing political diatribes that made the magazine a spokesman--definitely not a spokesperson--for America’s socially and culturally conservative lower-middle class. “Hypocrisy,” Heidenry comments, “was a factor in the Digest’s’ editorial mix from the very start.”

While the magazine preached the sanctity of marriage, refused to accept cigarette advertising and fulminated against the evils of alcohol, Wally himself was a flagrant womanizer, heavy smoker and ardent lover of cocktails. His top staff followed suit: “So many editors and executives shed their first wives, soon after going to work for the company,” Heidenry notes, “that having an affair with a secretary or colleague was jokingly referred to as a precondition for advancement.”

This duality had its roots in magazine’s launch during the tumultuous 1920s, when a flood of non-Protestant immigrants were remaking the nation’s ethnic composition and its Jazz Age children were flouting its moral standards. Born in 1889, the son of a professor at a small Presbyterian college in Minnesota and the grandson of a Presbyterian minister, Wally shared his readers’ nostalgia for the allegedly simpler and better America of their small-town childhoods. That didn’t mean he had any intention of denying himself the worldly pleasures to which the Digest’s success increasingly gave him access.

What a success it was! Launched in 1922 with a press run of 5,000, it was selling 220,000 copies a month by 1929. That year, Wally enlisted the services of promotional genius Albert Cole, who by 1939 moved more than 900,000 copies through newsstands alone. Total circulation reached 10 million in 1955, 12 million in 1960, 17 million in 1970.

The Digest’s editorial stance was as conservative as its business practices were innovative. Heidenry wittily captures the magazine’s essential personality with thumbnail descriptions of the uplifting pieces that made it the Bible of Middle America, from lurid medical articles promising miracle cures to relentlessly cheerful bromides for self-help, capping this with the apocryphal headline staffers jokingly suggested would be the ultimate Digest article: “New Hope for the Dead.”

His coverage of the ways in which the magazine advanced Wally’s political agenda is less satisfactory, although conscientious. He traces the process by which the Digest, which began as an excerpter of other periodicals’ material, gradually began assigning original articles but, by “preprinting” them in complaisant journals, maintained the fiction that it was selecting work “of enduring value and interest” rather than promulgating its own point of view.

He examines accusations made by journalists that the magazine, in its international editions in particular, often printed articles planted by CIA operatives and explores the possibility that the Wallaces were involved in the messy financial shenanigans surrounding the Watergate scandal. But he never comes to any definite conclusions about these controversial matters.

This reluctance to offer his own opinions is one of two major problems with Heidenry’s worthwhile but flawed book. Drawing on extensive interviews with former Digest staffers, the author vividly re-creates the provincial atmosphere in Pleasantville, which might have been 400 rather than 40 miles from Manhattan for all the interest its residents took in the activities of other publishers.

But, perhaps for legal reasons, he couches all his analysis in terms of other people’s opinions about goings-on at the higher levels of the RDA, from Wally’s affair with Lila’s niece to the trustees’ 1984 decision to unseat editor Ed Thompson, who made the mistake of running a few articles critical of the Reagan Administration and an insufficient number of positive stories about ordinary folks’ triumphs over adversity.

The second problem is related to the first. Lacking the organizing framework that a point of view would have provided, Heidenry has failed to winnow down his admirably thorough research into a manageably sized work with a coherent narrative flow. The subtitle’s description of this as “the uncondensed story” is all too apt; it would have greatly benefited from the ministrations of one of the Digest’s expert excerpters, who were never afraid to shape material to make a point. An abundance of juicy information about one of America’s most secretive corporations makes this a must-read for anyone interested in the history of American publishing. A more cogently written book, however, would have appealed to a much larger audience.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.