Exxon Valdez Stays as Symbol of Tanker Risks : Its name has changed but it still carries oil in a fragile single hull. Little has been done, critics say, to implement landmark 1990 protection law.

When a 987-foot tanker once known as the Exxon Valdez slipped into a harbor in the Bahamas a month ago, it was sporting a rebuilt hull, a new coat of paint and a new name--the SeaRiver Mediterranean.

Much about the ship had changed since it struck Bligh Reef five years ago and spilled 11 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound. But to the Greenpeace activists who met the ship with noisy protest in the Bahamas, little was different. It was the same old single-hulled ship carrying the same old cargo of oil, bearing the same old risks of environmental disaster.

Five years after the nation’s worst oil spill, environmental and maritime experts said the repainted Exxon tanker is emblematic of U.S. policy toward oil spills: In some ways, much has changed. And in some ways, little is different.

What has changed, primarily, are state and federal laws governing the design and operations of all ships operating in U.S. waters. The most significant law, the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, was passed a year after the Exxon spill to create a sea change in oil-spill prevention and response.

The Coast Guard is carrying out the Oil Pollution Act and contends that the changes are well under way. But critics in the environmental community accuse the Coast Guard and its masters at the Transportation Department of foot-dragging and charge that the changes called for by law are stalled.

The Oil Pollution Act called for significant new capabilities in fighting spills at ports around the United States. It required that ports and ship owners operating in U.S. waters put together plans for responding to spills.

It stiffened liability laws, increasing eight-fold the costs for which the owner of a tanker could be held liable and, in some cases, providing for unlimited liability. It established a 5-cents-a-barrel tax on crude oil to build a $1-billion cleanup trust fund.

And it set forth a timetable, running from 1995 to 2015, for requiring new, safer double hulls on large new cargo carriers operating in U.S. waters.

So far, the Coast Guard has created three new oil pollution strike teams and a National Strike Force Coordination Center in Elizabeth City, N.J. The Coast Guard has identified 19 ports where oil-spill equipment should be based and has virtually finished putting that equipment in place. In a spill of diesel fuel off Puerto Rico in January, several of those sites provided the necessary equipment.

The provisions of the 1990 law that increase potential liability also appear to have brought improvements in tanker safety. Ship owners and operators facing the prospect of greater liability concede they have paid more attention to the conditions of their equipment and the safety of their operations.

“I think it’s fair to say the liability was another piece to crystallize our thoughts,” about spill prevention, said Art Stephen, external affairs adviser for SeaRiver Maritime Inc., a wholly owned affiliate of Exxon Corp. and owner of the Exxon Valdez.

Experts on all sides of the debate agree. And because little oil is ever recovered from spills, even in the most favorable circumstances, prevention is a critical element of efforts to reduce the environmental impact of oil transportation.

Finally, the Exxon Valdez disaster had a powerful impact on coastal communities potentially affected by tanker traffic, galvanizing citizen watchdog groups. In the communities fouled by the Exxon Valdez, the Prince William Sound Regional Citizens Advisory Council--with a full-time staff paid with funds furnished by Exxon and other oil companies--has become a powerful, independent voice in ensuring safe operations.

Still, much today remains the same since the Exxon Valdez lurched onto Bligh Reef on March 24, 1989. Today, 95% of the vessels hauling oil in U.S. waters have a single hull, which can be easily breached in a grounding or collision. And a required plan to increase the safety of operating those ships, at least two years overdue already, is not expected to be complete for another year.

Earlier this year, the Coast Guard unveiled a plan to make single-hulled ships safer, but it was quickly withdrawn after an engineering firm determined that the plan actually could worsen a spill.

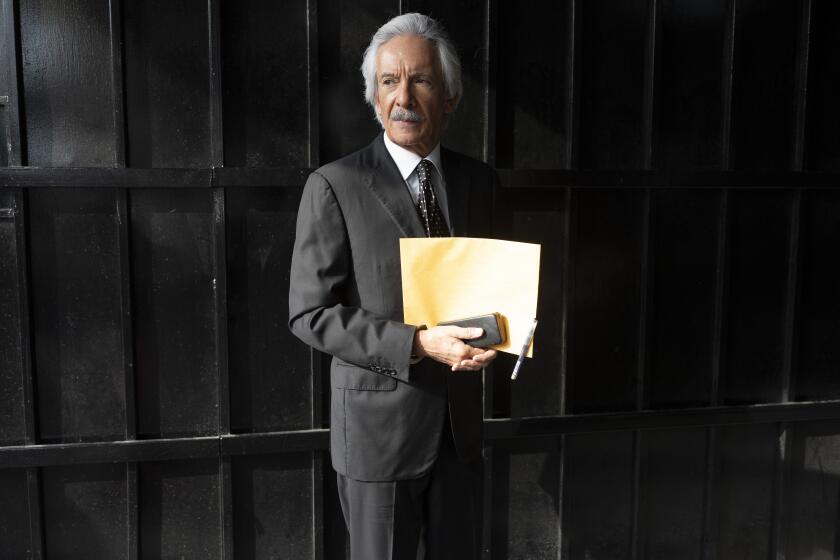

“We’ve been very concerned about the Coast Guard’s lack of competence and diligence in doing this,” said Sarah Chasis, a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council in New York.

Watchdogs like NRDC also worry that four years after the passage of the Oil Pollution Act, the Coast Guard has yet to identify environmentally sensitive shipping routes that should be free of oil tankers, as the law required.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.