New Owners of MCA Boost Hopes of Local Charities

When Edgar Bronfman Jr. declared on Sunday that buying control of MCA Inc. gave him a seat at “the table,” local charities might well have salivated.

That’s because the city of Los Angeles will not just be getting a new corporate leader when he takes control of the entertainment conglomerate next week. It will also welcome a business presence by one of the leading families in the world’s Jewish community--and one of the last of the big-time donors.

“This might be a real boon to us,” said Jack Shakely, president of the California Community Foundation, a charitable fund-raising organization.

While charitable giving by U.S. corporations nationwide has slipped over the past decade, donations by Joseph E. Seagram & Sons--the U.S. subsidiary of the Canadian liquor and juice company controlled by the Bronfman family--jumped almost 80% in the past two years, from $5.6 million in 1992 to an estimated $10 million in 1994.

The Bronfmans declined to comment, but Seagram Co. spokesman Chris Tofalli said the company has “always been a good corporate citizen and expects to continue that tradition in California.” He pointed to a recent $100,000 contribution by the firm’s Absolut vodka brand to the American Film Institute, and many music festivals sponsored around the state by Seagram’s rum, whiskey and tequila brands.

The leading recipients of Bronfman family largess in the past have been East Coast and Canadian Jewish and educational organizations. As the family turns its attention to its new Southern California enterprise, Los Angeles political and religious leaders hope the Bronfmans will now take a more active role in West Coast charities.

“This is good news for the Los Angeles Jewish community and the community as a whole,” said Rabbi Marvin Hier, founder of the Simon Wiesenthal Center. “This family takes their charity very seriously.”

Indeed, Seagram Chairman Edgar M. Bronfman has been called the “president of world Jewry” for his role over the past two decades as head of the World Jewish Congress. His brother, Charles, is the longtime patriarch of Jewish community life in Montreal, the company’s headquarters, and a major investor in Israel.

Their father, Samuel Bronfman, was chief of the Canadian Jewish Congress for many years. And 39-year-old Edgar Bronfman Jr., president of Seagram, will be chairman of a World Jewish Congress dinner honoring his father in New York on April 30 that will be attended by 1,400 people, including President Clinton.

“The Bronfman name has been synonymous with Jewish leadership for decades,” said Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, who began his own public life as an activist seeking the freedom of Soviet Jews, a favorite Bronfman cause. “I’m hopeful that they will play as active and meaningful a role here as they have in New York and Montreal.”

The younger Bronfman, called “Effer” inside the family, appears to be interested in a wider range of philanthropy than Jewish causes. He sits on the board of the New York Public Library and has worked actively to bring about understanding between minority groups in that city, his hometown--where he says he will continue to live.

“His philanthropy is more general--his father has the corner on the Jewish market,” said a longtime associate familiar with father and son, who are both U.S. citizens, although their company is based in Canada.

In that vein, the Bronfman Foundation donated $50,000 to the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People in 1992, $50,000 to the Urban League and $50,000 to We Will Rebuild, a hurricane-relief outfit in Coral Gables, Fla.

Fund-raising organizations that rely on corporate giving in Southern California are especially needful of a new benefactor.

Local corporate contributions have withered away as major donors have merged out of existence, downsized or suffered profit declines, according to Shakley, the California Community Foundation director. United Way contributions--collected principally from the employees of medium-sized and large corporations--have declined 40% in the past five years.

When Los Angeles-based Security Pacific merged with San Francisco-based Bank of America, for instance, Shakley said, its $2 million in local contributions vanished. Likewise, when New York-based Texaco bought Los Angeles-based Getty Oil, he said, Getty’s $7 million in annual local contributions dried up.

Executives of local charities hope Bronfman will kick up activity by the MCA Foundation, which in 1993 disbursed $749,000 in grants. By contrast, the Walt Disney Co. Foundation gave $1.6 million, American Express gave $12.4 million and Exxon $19.8 million, according to the 1995 Foundation Directory.

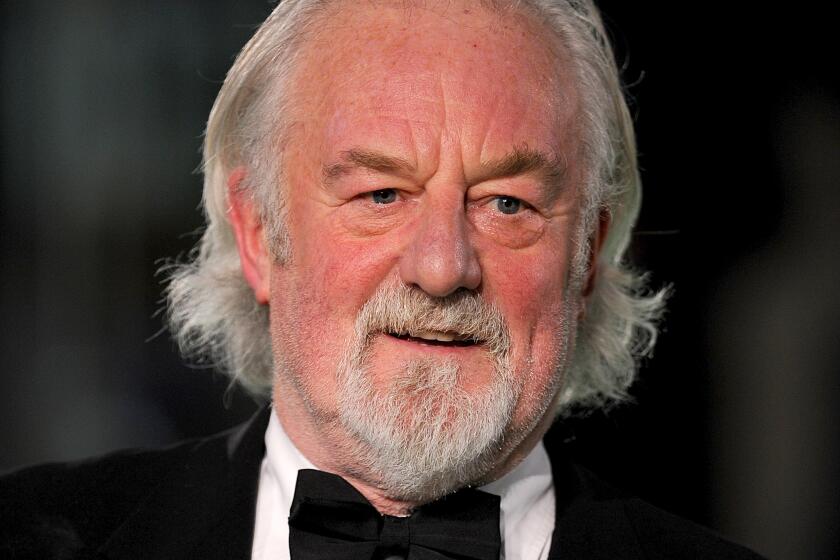

To be sure, top executives of MCA have been important contributors to local causes for years. Just three months ago, MCA Chairman Lew Wasserman chaired a dinner at the Simon Wiesenthal Center held to honor his lieutenant, MCA President Sidney Sheinberg, and wife Lorraine. The affair netted a record $2 million for the center and its Museum of Tolerance, according to Rabbi Hier.

“Charity plays a very important role in the way they see their corporate responsibilities,” Hier said.

But the Bronfmans, and the Bronfman Foundation, are in another league, charity managers say.

“I think they are going to become big players in Los Angeles,” said Carol Plotkin, executive director of the American Jewish Congress, a civil rights organization. “While some individuals at MCA are Jewish and have made personal contributions, the organization has not participated in organized Jewish life in Los Angeles like the Bronfmans have in New York and Canada.”

In 1992, the latest year for which details are available, 36% of funds disbursed by Seagram’s grant-making arm, the Samuel Bronfman Foundation, went to Jewish causes: $1 million to the Edgar M. Bronfman Center for Jewish Life in New York, and $1 million to the World Jewish Congress. In Montreal, the Canadian Jewish Congress office is located in a building called the Samuel Bronfman House that also houses a museum and archive documenting Canadian Jewish life.

The foundation has also been lauded for funding hundreds of scholarships for youths who wish to study in Israel, as well as professorial chairs in business and Jewish studies, and student activity centers, at Columbia University, New York University, Williams College and elsewhere. Nationally, the Seagram-financed foundation established the Meals on Wheels America program, which provides hot food to the homebound elderly in 45 cities.

The senior Bronfman’s personal fortune of $2.5 billion makes him one of the 20 richest Americans, according to Forbes magazine. He was the top contributor to the Republican National Committee in 1992, giving the party $450,000, according to reports filed by the party with federal election officials.

If the Bronfmans raise the level of philanthropy at MCA, they may succeed where the entertainment firm’s former parent, Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., failed at building an integrated corporate esprit.

“Matsushita has a sophisticated, global philanthropy strategy that they never extended to MCA,” said Craig Smith, president of Corporate Citizen, a philanthropy think tank.

“They failed to achieve philanthropic synergy, and it cost them. If they had had projects where they had all worked together to try to solve the world’s problems through entertainment, for instance, they could have developed relationships that might have helped them avoid the miscommunications that became the emblem of their life together.

“They didn’t engage the folks in Los Angeles at the level of values. That’s what corporate philanthropy does for a company.”

Notwithstanding the Bronfman family’s commitment to social issues, beverage industry analyst Jacques Kavafian of Levesque Beaubien Geoffrion, a Montreal securities firm, sees their civic contributions in the context of the corporate strategy of a booze-maker.

“Seagram is extremely highly regarded by the communities they operate in, and that’s partly because of the products that they sell,” he said. “They have to bend over backwards to be nice guys.”