A Kaleidoscopic Life : From naughty school boy to reclusive squire : EVELYN WAUGH: A Biography, <i> By Selina Hastings (Houghton Mifflin: $40; 724 pp.)</i>

I write these words from a fast up-and-coming European country called Ireland and from a house haunted by the ghost of James Joyce, who once visited here. And haunted too, by other literary gentlemen who roamed along these verdant byways of Westmeath, namely Evelyn Waugh, who actually thought of buying my home and who is the present subject of this quite marvelous biography by Selina Hastings.

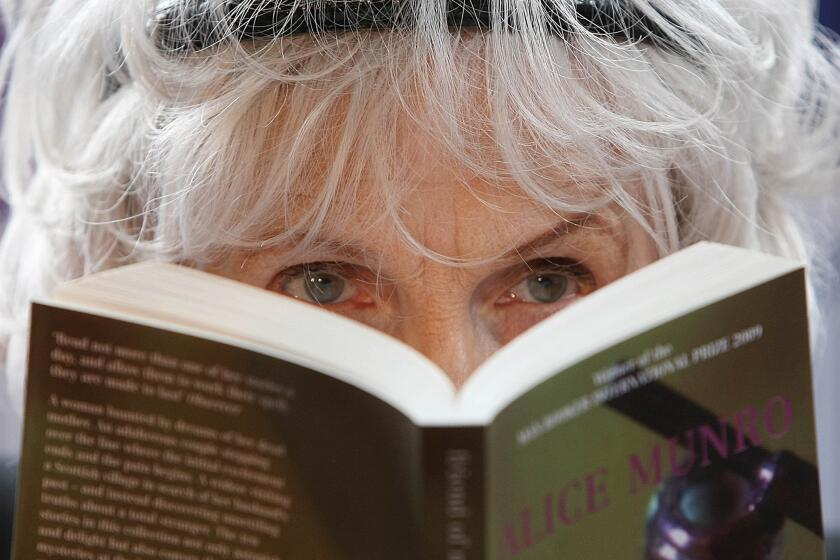

On the jacket cover, Waugh stares at you with no-nonsense eyes. But his life was in fact a kaleidoscope of roles. Waugh emerged from each phase an entirely new and different person: naughty school boy, officer and gentleman and finally the reclusive squire puffing cigars and quaffing after-dinner port on his country estate.

Hastings depicts Waugh’s life so vividly that one can nearly hear his best eccentric aristocratic vowels issuing de rigueur insults toward the many he thought so deserving around him: “I’ll abbreviatedly thank you not to morally or intellectually muck about with me, you low cur.”

Juxtaposed with male friends, there are Waugh’s lifelong platonic friendships with highly intelligent and beautiful women as well as an elaborate documenting of his public school homosexuality, the latter being done in such a subtle way as to portray Waugh as the eventual practicing heterosexual he was to become.

And then, as immensely important as such things are to Europeans, every step in the awakening and honing of Waugh’s lifelong snobberies is documented, as he and Frank Pakenham, later Earl of Longford, “climbed the slopes of London society together” to comport in patrician circles. We see, through both text and photographs, an elitism of a kind that knows no rival: tweeds, walking sticks, fox hunting kit, and poses on the stoops of stately homes in leather boots and shiny black bowlers, along with suitable facial expressions to reflect the splendor.

Although Waugh took on these appurtenances of the upper crust, he was no real snob--as a snob no real author can afford to be. And he did in this regard as a writer make it known that “I reserve the right to deal with the people I know best.” Which indeed to know them even better, one supposes also involved the celebration of the self-indulgent: smoking and drinking to excess, remaining unbothered to be physically unfit and delighting in the epicurean. Although missing out on serious shooting and fishing, it was clearly advantageous for Waugh to maintain a patrician bias that suited his notions of superiority, and thus, as Hastings writes, he “assumed a part that much appealed to him as that of landed country gentleman.” Waugh even maintained that he would have liked “to have been descended from a useless Lord.” But when he married his second wife Laura, his in-laws the Herberts found “disturbingly vulgar his exaggerated admiration for the upper classes.”

Now then. I don’t know who anymore, across the United States (where an ascent from no-account beginnings may be sung from the roof tops) gives much of a fig in the matters of social standing and climbing. But Hastings’ account of the agony and bitter peril encountered by those Europeans who attempt to step up a notch, as well as the doom for those who try and don’t succeed, will surely encourage those born and bred on the American continent to count their blessings.

Hastings makes amply clear why Waugh has attracted so much scrutiny as to his social credentials, which weren’t in fact, seen from an American point of view, half bad. Damn decent in fact. However, as one has already averred, authors must embrace all of the social world and thus cannot afford to be snobs or social climbers; one might instead say that for his practical day to day use, Waugh merely posed as one. In any event, in these pages there is more than enough evidence for readers to form their own opinions.

Ah but then, my goodness, just as one has established Waugh’s credentials as a gentleman, comes an odd bomb shell: Waugh might have had an exaggerated admiration for the upper classes, but he could take liberties with and even be destructive and unmindful of the impression he made upon the kaleidoscopic array of your upper-echelon characters of the time.

Staying as a guest of his friend Alistair Grahman at Barford country house, for instance, Waugh ripped out the Africa page of their big Times atlas. This ungenteel act would have to be regarded as not the behavior of a gentleman and such news getting around could put paid to your social climbing for all time. As it did instantly with Graham’s mother, a very proper American from Savannah Georgia.

This tome is unobtrusively packed with facts and so many vivid descriptions that again and again one has to glance at Selina Hastings’ youthful author photograph to know that she could not have been there. In the stories unfolding of travel, university and his later squirarchical existence, all serve as brilliantly wonderful explanations if not an apologia for Waugh’s churlishness and for the life led then: Where your once hysterically pukka vowels were the prow by which you pierced your way to succeed and alerted others to your esteem. Now they are no longer proclaimed aloud, except perhaps in the dustier corners of your better clubs, making this not so distant past enlightening to read today, when America’s “power” accent has the last word, and culturally conquers all.

Waugh has to be your genuine eccentric. While eager to join the war against Hitler (he served as an officer throughout World War II), he spent much of his time dining and seeing old friends; Hastings gives brilliantly amusing descriptions of his close combat with boredom and some of best renditions of English one-upmanship that can be found. While known to be brave, he was perhaps the only man in military history who was thought by his senior officers to be too rude and offensive to be allowed to go into battle.

After the war, Waugh retained his reputation in America, where he spread his incivility from coast to coast. One would have liked to have been eavesdropping when he paid his visits to Forest Lawn Memorial Park, certainly one of America’s most astonishing places, as can be seen in Waugh’s magical account of its existence, “The Loved One.”

Finally, we find Waugh, his entry into the world of the landed gentry secured, living in the country house surrounded by your few sylvan acres--perhaps without the mile-long entry drive and the agreeable vista of parklands viewed from a stately home’s mullioned windows, but nevertheless a reasonable resemblance to a lordly abode. One could also find him at White’s, the kind of tony London club where members took their satisfaction on rainy days by gazing out the club windows at the passing damn public getting wet. Hastings must know more than a few club men, for she vividly evokes the ennobling contentment and comfort to be found in such precincts. A refuge which Waugh more and more sought and seemed deeply to enjoy in later life, and why not? Where a gent in blissfully male exclusivity could pleasantly contemplate his self-esteem and where, over his second gin and tonic, had he the imagination, could let his senses merrily waft in the breeze of reverie.

In his life lived, Waugh seemed to achieve greatest contentment while still in his early thirties, and at the time of his second marriage to Laura, mother of his children. He is then described as being “good looking, affectionate and with enormous charm, funnier than any man alive.” At these moments it’s hard to remember just as strongly an opposing view from a schoolmate who described the young Waugh as “an exhibitionist with a cruel nature that cared nothing about humiliating his companions so long as he could expose them to ridicule.”

This surely is a brilliant pen, which wrote this tome about a writer who richly deserved to be so written about. Hastings ends with words not much different from Waugh’s most descriptive: His “last years were bleak and wretched but his death was an unparalleled blessing, dying shriven on Easter Sunday, the most joyful day in the church’s year.” They are words that come close to ending this astonishing book about an astonishing man who even as he lies contented in his grave still serves so well to inspire the courageously curmudgeonly in all of us.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.