PERFORMING ARTS : The Film-Fan Man : John Mauceri, with Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, is on a mission: to bring American movie and show music to a much wider audience.

In a big marketing push, Philips Classics created the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra in 1991 to fill the gap left by the Boston Pops’ moving to a new label. At the same time, the Los Angeles Philharmonic wanted more summertime freedom to pursue European tours. A new orchestra could take over some of their dates at the Bowl. Everybody would come out a winner.

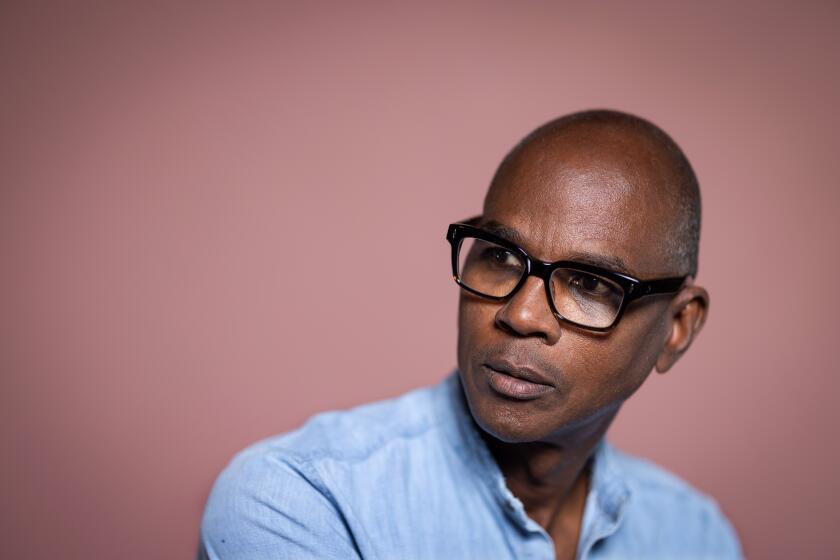

Especially conductor John Mauceri, who was handpicked by Philips to lead the group.

His mandate? Attract a large audience to the Bowl, make recordings for Phillips--now up to 10 CDs--and explore a range of repertory from pops to film music to classics to Broadway to, well, pops.

He’s done just that.

“I’ve learned a lot about music I didn’t know much about before, which is good because I basically am a person who likes to study, likes to learn and tell people what I’ve learned,” Mauceri said the other day from his summer home on Long Island, where he was taking a short holiday before his first Bowl concert last Wednesday.

For his five-year tenure, at least one or two nights of film music--with the orchestra accompanying clips--and Broadway show tunes, as well as some folk music and general pop, have been included on the Bowl schedule, and on the CDs that the orchestra has produced.

By including such music--especially film scores--in his orchestra programs, he feels he’s catching the next wave.

“We’re seeing a major shift in repertory in orchestras, and not just in America,” he said. “We’re getting requests from Poland, Germany and Sweden for the [film] music we’ve done. The recording medium is so strong that wherever I go in the world to conduct, there are people who like the recordings and people requesting the music--they’re not looking at it as something ghettoized.”

The role of a popularizer was not a predictable one for Mauceri, given his serious music background.

Born in New York City in 1945, Mauceri graduated from Yale and taught composition and conducting there for 15 years. He was a conducting fellow with Seiji Ozawa and Leonard Bernstein at Tanglewood in 1971.

He served as music director of the Washington (D.C.) Opera from 1980-82, the American Symphony Orchestra in New York from 1984-87 and the Scottish Opera from 1987-94. These days, when he isn’t at the Bowl or recording with the orchestra, he’s usually guest conducting at “heavy” orchestras around the world, often giving premieres of works composed in America.

As his conducting life has expanded, so has his recording career. In addition to Philips, he is one of the principal conductors for London/Decca’s “Entartete Musik,” a series of recordings of works that were banned, destroyed or lost during the Nazi Third Reich and other eras of political suppression.

Mauceri sees a connection between this music and Los Angeles.

“A lot of the European composers who came to Hollywood were on Hitler’s list,” he said. “But if you survived the Holocaust, you were punished because you survived. Germans [today] never play Schoenberg’s music that was written in America. Same with Hindemith. They never play Hindemith’s American music.”

The stigma, according to Mauceri, is even stronger against refugee composers who wrote film scores as well as more serious music. He mentioned, in particular, Miklos Rozsa, who wrote more than 50 film scores, including that for the 1959 “Ben Hur,” and Erich Wolfgang Korngold who composed music for more than a dozen Warner Bros. films, including “The Adventures of Robin Hood.”

“Rozsa, who was born in Hungary and when his music was ‘Hungarian,’ it was played,” Mauceri said. “After he became an American citizen and lived in Hollywood, nobody played his music.

“When I went to Hanover to conduct Korngold’s Cello Concerto and Symphony in F-sharp--music written in Los Angeles--they, as Germans, didn’t know [this] music at all,” he added.

“Normally, I only talk [to audiences when I conduct] at the Bowl, but I did say, ‘This is where your culture and my culture meet--your history and my history meet. They meet at the border of serious music and popular music.’ They have to confront the snobbery of what is considered serious music.”

Programming in that border land for the Bowl concerts is a group effort, says Mauceri. It involves Philharmonic Managing Director Ernest Fleischmann and Anne Parsons, general manager of the Bowl, among others. And a lot of it has to do with guest soloists.

“We all kind of make programs together. Sometimes the Philharmonic or the marketing department decides there’s a soloist, or a kind of soloist, that is missing [and] that is desired for the summer. Sometimes the soloist is offered to me as a possibility and I can, I suppose, say no, perhaps.

“This is a fairly complicated issue. For the most part, it depends on the pool of available soloists. Most famous soloists who tend to be enormously successful are enormously expensive. The least-known don’t necessarily draw the audiences. So it’s the great in-between. . . .”

Still, he said that he handpicked such soloists as soprano Jane Eaglen for the Opera Night on Friday and mezzo-soprano Marilyn Horne for the America the Beautiful programs, July 2-4.

“Each concert is a journey,” he said. “Since I talk to the audience, I also have them share in the journey.”

The journey involves finding a theme through “certain ways of mixing and matching and combining. It’s a pattern match,” he says.

For instance, the Great America Concert (July 14-15) combines “the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II with two Rodgers and Hammerstein works about World War II and the 50th anniversary of John Raitt’s Broadway debut in ‘Carousel.’ John will make an appearance in the second half of the program.”

This year’s film music extravaganza, on Aug. 27, is a salute to the 100th anniversary of cinema. “The entire world is celebrating the 100th anniversary of cinema,” he said. “Every town in Europe has concerts, but it looked like nothing was happening in Hollywood. So we will show films and play film music.”

None of this is as easy as it sounds.

When it comes to film music, “you have to get permission to show the film excerpt,” says Mauceri. “Then you have to make a print of it. Then you have to get the film scores or restore them, then time them up.”

Over a summer, he estimates he has to add “somewhere in the neighborhood of 175 pieces of music” to the repertory he is already familiar with, because some of the soloists, singers mostly, bring their own arrangements.

Although New York City is Mauceri’s home, his busy schedule prevents him from spending much time there with his wife and son. Does he like life on the road?

“It has nothing to do with ‘like’ anymore,” he said. “It’s beyond ‘like.’ It’s what I do. I find joy in this life and I find tremendous sadness and loneliness in a lot of it. But the overall process seems to be achieving a large worldwide recognition of music that I think ought to be heard, that is redefining what American music is, not only in America but also in Europe.

“I consider myself an emissary for 20th-Century American music. I’m honored conducting these pieces, having this great orchestra playing this music that has waited about 45 years to be played by a great orchestra. This is a privilege for me. I don’t think I ask the question whether it feels good or bad anymore.”

More to Read

More to Read

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.