FBI Seeks New Laws to Fight Economic Spying

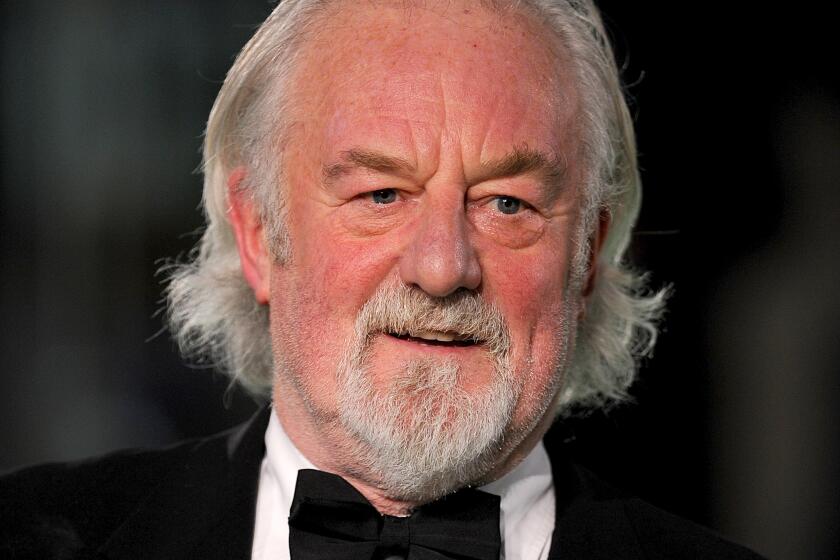

FBI Director Louis J. Freeh asked Congress on Wednesday to give the bureau greater legal authority to counter rampant and fast-growing economic espionage against the United States by both friendly nations and traditional adversaries.

Freeh said the FBI is now investigating 800 cases of economic espionage against the United States, double the number of just two years ago. He warned that the intelligence services of at least 23 nations now make U.S. industry a prime target of their espionage and said the steep increase “presents a new set of threats to our national security” in the post-Cold War world.

Economic and technological globalization, Freeh added, have combined “to increase both the opportunities and motives for conducting economic espionage.” As a result, the FBI has stepped up its counterintelligence efforts to thwart foreign spy operations in Silicon Valley and other high-tech hot spots.

Freeh did not identify the countries now conducting economic spying against the United States. But other intelligence sources said Wednesday that France, Israel, Japan, Russia and China are among those nations that have mounted major espionage against U.S. industry.

The Russian intelligence service--the Federal Counterintelligence Service, or SVR--has even upgraded the status of its so-called “Directorate T,” its unit charged with obtaining foreign technology and countering attempts to steal Russian technology, U.S. sources said.

Japan has been quite successful in penetrating U.S. corporations, usually in an effort to obtain pricing data or the negotiating strategies of American firms, rather than technology, sources said.

U.S. officials said Japan has succeeded without the use of electronic eavesdropping--relying instead on recruitment of human agents within corporate America. “I’ve always been amazed at how well the Japanese do,” said a U.S. source.

In contrast to the Japanese, Chinese spies try for basic technological secrets of U.S. companies, sources said, while French spies have become notorious for brazenly targeting U.S. executives who are traveling in France.

Sources added that Iran is aggressively spying throughout Europe in an effort to obtain technology with defense applications but also has sources in the United States.

Freeh said the United States needs new laws specifically targeted against economic espionage to strengthen the government’s hand in pursuing industrial spy cases. He said no current federal statute directly deals with economic espionage or with the protection of economic information in a thorough way, forcing the FBI and Justice Department to rely on mail fraud laws or other statutes that may not be suited to the prosecution of espionage.

“Only by adoption of a national scheme to protect U.S. proprietary economic information can we hope to maintain our industrial and economic edge and thus safeguard our national security,” Freeh told a Senate hearing conducted jointly by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and the Senate Judiciary subcommittee on terrorism, technology and government information.

In some cases, Freeh said, the FBI has been forced to abandon its investigations of economic espionage because there were no federal laws that provided a clear basis for prosecution. Often, espionage in the area of intellectual property leaves the FBI in a legal gray area.

Freeh noted one case in which a U.S. auto maker involved in a licensing agreement with one foreign firm complained that its partner gave secret data to another foreign company. But the Justice Department refused to prosecute, arguing that U.S. law required an actual theft of physical property, not “an idea or information.”

“There are gaps and inadequacies in existing federal laws,” Freeh noted, which call for a “federal statute to specifically proscribe” economic espionage. Several bills have been proposed in the Senate to close the legal loopholes and target economic espionage as a clear federal crime, including a measure that would make theft of proprietary information a federal crime punishable by up to 15 years in prison and a $250,000 fine for individuals and up to $10 million in fines for companies.

Estimates of the cost to the U.S. economy from the damage done by foreign economic espionage vary widely but are clearly rising. As an example, Freeh noted that an FBI undercover investigation in 1990 revealed a plot against drug makers Merck & Co. and Schering-Plough to steal pharmaceutical trade secrets worth as much as $750 million.

Freeh said that foreign intelligence services often set up false front organizations in the United States, including “friendship societies” and import-export companies, as bases from which to conduct economic espionage.

But the best sources for foreign spies are usually people in U.S. firms eager to sell what they know. U.S. consultants, including former U.S. government officials, often are hired by foreign countries as part of economic espionage operations.