One Man’s Mission That Has Rhyme and Reason

For Andrew Carroll, it all started with a few simple words he put in a letter to Joseph Brodsky, the poet who had embarked on a mission to turn Americans away from television to poetry.

“If there’s anything I can do to help, let me know,” wrote Carroll, an impressionable English major at Columbia University in New York.

Within two weeks, Brodsky sent an answer. Yes, the poet wrote, let’s talk.

Prompted by that exchange six years ago, Carroll, 28, is zigzagging across the country in a Ryder rental truck, handing out books of poetry. Since beginning his journey a month ago, he has handed them out on farms and in the inner city; he’s given away poetry in diners, jury waiting rooms, supermarkets, nursing homes, truck stops and a Louisiana prison.

The upside, Carroll said, is the rewarding work. The downside is that his mentor died two years ago and his marriage-minded girlfriend dumped him about a month before he arrived Sunday in Los Angeles.

Driven by a keen sense of purpose, Carroll is undaunted. “This trip is about more than poetry,” he said. “It’s bigger than that. It’s about literacy, the importance of learning in an increasingly technological age, with its computers and video games.

“We’ve lost a sense of craft, our dialogue has suffered,” said Carroll, a member of the Academy of American Poets. “That’s what we’re looking for, insight into human nature. That’s why we listen to news, to gossip. We’re trying to learn ways to live. Poetry offers that better than almost anything.”

Carroll’s objective is to put 1.5 million books of poetry in people’s hands. The Doubletree hotel chain, one of his sponsors, has agreed to put a book of poetry in each of its rooms, right beside the Gideon bible.

“Before this trip, I had only driven 300 miles at one time in my entire life,” Carroll said. “The most I’d done is, like, a day trip to the beach. It wasn’t meant to be a symbolic drive across America. The point was to get to as many communities as possible.”

By the time he reached Union Station in Los Angeles, Carroll had become a quasi-celebrity. Jerry Walker, a taxicab driver, recognized Carroll from a feature he’d watched earlier in the day on the CBS-TV show “Sunday Morning.”

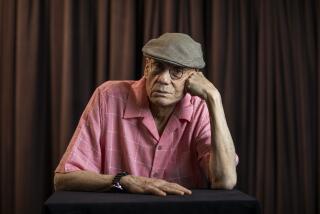

The man Walker saw did not look much like a stereotypical poet. His hair evoked memories of Richie Cunningham in the TV sitcom “Happy Days,” and he wore horn-rimmed eyeglasses, a green polo shirt, khaki pants, white tube socks and buckskin shoes. Still, he had a bard’s zeal.

“When I saw him, I recognized the package. It was pattern recognition,” said Walker. “I thought, ‘I’m gonna get my book.’ ”

Walker waited patiently as Carroll spoke with a talkative Janet Ward, who was waiting to board the Amtrak Sunset Limited to New Orleans.

*

Like almost everyone Carroll approached, Ward took a copy of “101 Great American Poems.” He also carried “African-American Poetry” and a book of Spanish-language poems.

Ward said she accepted the stranger’s gift because “he was very clean-cut.”

The letter that started Carroll on his journey was written by a clean-cut 22-year-old who read a speech Brodsky delivered in 1991 to the Library of Congress; the speech was printed by The New Republic magazine.

The young man circled the parts that moved him. “I am here to speak not about the predicament of the poet, who is never, in the final analysis, a victim,” Brodsky said. “I am here to speak about the plight of his audience: about your plight as it were.

“The blue-collar is not supposed to read Horace, nor the farmer in his overalls Montale or Marvell. Nor, for that matter, is the politician expected to know by heart Gerard Manley Hopkins or Elizabeth Bishop. This is dumb as well as dangerous.

“There is now a discernible opportunity to turn this nation into an enlightened democracy. And I think this opportunity should be risen before literacy is replaced with videocy.”

*

Brodsky was a well-thought-of poet in the former Soviet Union who was arrested and sent to Siberia because he wouldn’t stop writing. He served more than a year of a five-year prison sentence.

Asked to stop writing, Brodsky said no. He was deported. After arrival in the United States, he became a poet laureate and consultant to the Library of Congress.

Brodsky died before Carroll, his most dedicated soldier, began his trip, which is funded by the Doubletree chain, the growers of Washington apples and by various book publishers.

Carroll’s rental truck was stuffed with 3,000 pounds of books when he started. That was down to about 500 pounds when he began his rounds in Los Angeles. When he leaves San Francisco near week’s end, he plans to have none.

Some might say it’s folly. They haven’t read the letters that pour in.

John Silver of Boston found a book of poems by the Bible in his hotel room and wrote he was “charmed beyond words. Not only did I start to read it that night, but I have been reading it ever since.”

Wendy Garcia wrote to say she reads from one of the distributed books to her 2-year-old son each night: “I’m not sure if he understood everything, if anything at all, but the important thing is that he laid back and smiled.”

The mission is far from accomplished. But, Carroll said Sunday, he’s made progress.

“There was a cologne commercial on what makes a man,” Carroll said. “It said, he’ll pass on poetry. I’ll pay for a trip for someone to say that to some of the prisoners I’ve talked to. Those guys are huge and they love poetry.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.