Search for Peace Brings Irish Labor Leaders to L.A.

A delegation of Irish trade unionists, looking for a way to make “peace” something more than a word on paper, brought their quest this week to the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Museum of Tolerance.

The purpose of the weeklong visit was to announce plans to create their own Belfast Museum of Tolerance--a symbol of peace in a land where sectarian conflict between Protestants and Catholics has cost more than 3,200 lives since 1969.

“It would be a living example not only to the victims of violence, but to the future as a continuing contribution to peace,” said Brian Campfield, president of the Belfast Trades Union Council. “It would be a place where people could confront their own prejudices. The issues are universal.”

Campfield and three other members of the Belfast union council came at an emotional time in the history of Northern Ireland, following last spring’s historic popular vote to set up local assemblies and to share political power.

But agreements on paper mean nothing, Campfield said, unless something is done to turn longtime combatants away from the conflict that has become ingrained in their culture and has left many Irish feeling that the current peace effort is only another calm before the storm.

At the Simon Wiesenthal Center, the delegation saw museum programs tracing the history of human prejudice, participated in computer interactive dialogues on race and heard the gripping tale of a Holocaust survivor. They escorted Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies through a day of diversity training, and dined with community activists, labor leaders and educators.

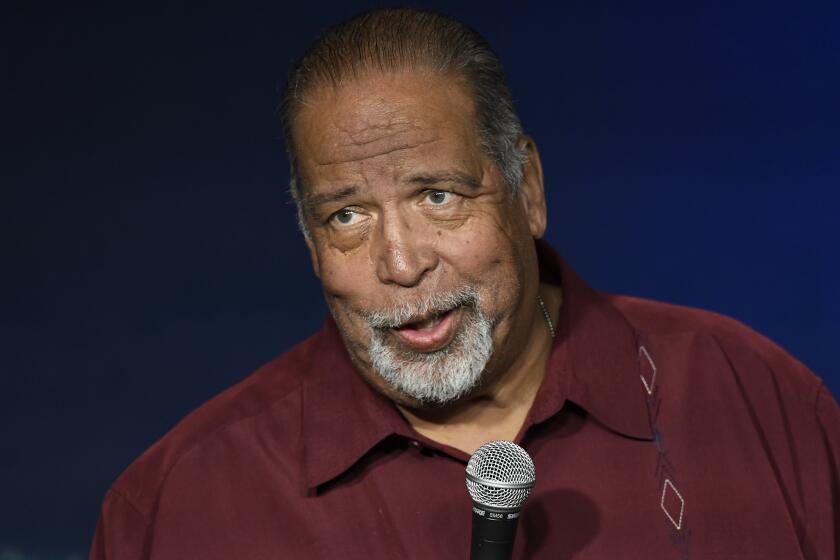

“It’s been a full day,” said Billy Robinson, a trade union member and director of Counteract, an Irish anti-sectarian organization. “The whole package is very powerful.”

The $50-million institution opened within a year of the 1992 riots to challenge visitors to confront issues of bigotry and racism, and to understand the Holocaust.

As a busload of elementary schoolchildren streamed into the center, followed by plain-clothed police officers going to a diversity training seminar, Robinson commented that in Ireland, “our police are very macho, like all police, and act as defenders of the state. But that’s changing. They are learning community policing.”

In seminars with police officers and discussions with community leaders, the delegates told stories of what life is like in a society divided by religion.

Andy Snoddy, an executive member of the Belfast Trades Union Council, said public statements that might be considered free speech in the United States can be prosecuted as hate crimes.

“It’s hard to enforce,” he said, “but one Protestant politician said that all Catholics should be put in gas ovens like Jews. He was charged with a crime, sentenced to a short time in jail and murdered a year later. His wife was elected to his seat.”

Changing such long-standing patterns of hatred will take time and education, said Desi Murray, the council’s secretary.

“We still have a divided society,” he said. “But violence is not an acceptable way of dealing with conflict.”

The labor movement became a beacon for change, Murray said, because unions had to cross sectarian lines representing workers of all faiths. Unions then began organizing demonstrations against discriminatory laws aimed at Catholics, which mirrored the civil rights protests in America’s South.

“We were born in a segregated society, live in a segregated society, go to school in a segregated society and we die and are buried in a segregated society,” Robinson said. “That is the stark reality.”

But the city of Belfast, known for its violence, can become a source of hope, Robinson said, “not with a memorial to the dead, but with a memorial to the living.”

Rabbi Abraham Cooper, the museum’s associate dean, said the Simon Wiesenthal Center will try to give the delegation technical support.

“We can give them nuts and bolts assistance, but it’s their vision and they have to hold on to it,” he said.

It is a vision that has been tested under fire.

At a gathering with community leaders and educators, a judge told the Irish delegation how impressed she was with their spirit. She asked them if they had any training in conflict resolution.

“Yes,” Murray said. “Living in Belfast.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.