Challenger to Germany’s Kohl Relies on Voter Fatigue

If the election strategy of Gerhard Schroeder could be synthesized into one slogan, that rallying cry would be: “I’m not Helmut Kohl.”

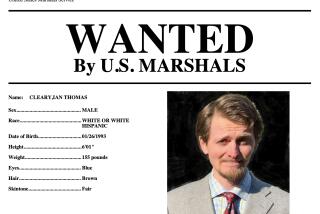

The jovial, even roguish, cigar-puffing governor of Lower Saxony, who aspires to unseat Europe’s longest-serving elected leader, has fashioned his campaign almost exclusively around voter fatigue with the portly, charisma-challenged incumbent.

Frustrated by 11% unemployment and by immigration and labor policies that have sent already celestial taxes soaring, Germans have soured on Chancellor Kohl’s 16-year tenure despite its glorious feat in reunifying this long-divided nation.

But as the rival campaigns accelerate toward a cliffhanging Sept. 27 conclusion, Germans have begun to wonder what change Schroeder and his left-of-center Social Democratic Party have in mind beyond a body swap of politicians with most of their political values in common.

Schroeder, 54, likes to cast himself as typical of the younger leaders now governing some of the world’s most prosperous nations, likening himself to President Clinton and Britain’s Tony Blair.

His untidy personal life may deprive him of votes from Roman Catholics, who make up 34% of Germany’s 80 million people. Although Germans pay far less heed to the sexual dalliances of their leaders than do Americans or Britons, Schroeder drew unflattering attention from German tabloids last year when he took up with a journalist 20 years his junior, Doris Koepf, and made her his fourth wife after a messy divorce from No. 3, the mother of his two teenage daughters, both born out of wedlock.

As much as 40% of the electorate remains undecided less than two weeks before the watershed vote, making Schroeder’s bid to topple Kohl all the more dependent on his finessing a balance between voters’ demands for a new direction and their well-known reluctance to upset the status quo. Germans actually vote for a party rather than a chancellor candidate, and the parties then negotiate a coalition to form a majority and the right to name a chancellor.

Although opinion polls still show Kohl’s right-of-center Christian Democratic Union running 3 to 5 percentage points behind Schroeder’s Social Democrats, Sunday’s vote in the populous and prosperous state of Bavaria gave a stronger-than-expected endorsement to Kohl’s sister party there, the Christian Social Union.

A recent poll by the respected Emnid organization questioned undecided voters about their reservations and found that 73% felt they either knew too little about the candidates’ platforms or saw too little difference between them.

Even Schroeder--although brashly confident about his chances to guide Germany’s shift of capitals from Bonn to Berlin before the turn of the millennium--appears to have problems describing how his leadership would be distinctive.

“Since economic policy has a lot to do with psychology, positive change can only be achieved with a new beginning. That means a new government,” Schroeder said in an interview at his offices in this wind-swept northern city.

Few Alternatives

His party champions many of the same tax reforms sought by Kohl’s Christian Democratic Union, and the challenger has vowed to maintain Kohl’s successful foreign policy priorities. Schroeder has been critical of Kohl’s policy toward foundering Russia but has said nothing about what he would do differently.

What Schroeder seems to be promising is that the revolutionary reforms needed in the cushy social welfare system can come about with a minimum of discomfort.

No. 1 on his list of projects, however, is a much-touted “Alliance for Jobs,” requiring deeper government investment to force down unemployment, which reached a post-World War II zenith of 12% in January.

Joblessness Shrinking

But in the homestretch of the campaign, which Schroeder led comfortably from his March declaration until mid-August, the labor picture slowly has begun to brighten. Economics Minister Guenter Rexrodt announced last week that the jobless rate in August shrank modestly for the fourth month in a row, to a still-worrying 10.6%.

Kohl has for months been promising a drop below 4 million jobless by the end of the year, down from the January peak, which approached the psychologically staggering 5-million level. Since the figures have been falling, Schroeder and the Social Democrats have accused Kohl of financing make-work projects in an electioneering scramble.

Although Rexrodt belongs to the Free Democratic Party, which is aligned with Kohl’s Christian Democrats, his insistence that “we have achieved a turnaround on the jobs market” was echoed by independent economic analysts across the country.

Schroeder describes himself as “pragmatic” when explaining the dovetailing of his views with those of his opponent, such as his support for continued development of nuclear power and his appeal for a hefty corporate tax cut.

But in the actions-speak-louder-than-words department, Schroeder has shown himself to be more beholden to labor than his campaign posturing suggests. Earlier this year, he spent $580 million from state government coffers to derail the foreign purchase of the Salzgitter steelworks in his state to ensure that its 12,000-plus jobs remained secure. The enterprise was quickly privatized at a modest profit, but the governor’s intervention raised concerns that he may be vulnerable to the pressures of organized labor.

In another bow to Germany’s powerful unions, Schroeder has promised that, if elected, he will roll back the modest savings Kohl managed to push through the Bundestag, the lower house of parliament. Those reforms dropped corporate pension contributions from 70% of net wages to 64%, reduced sick pay for some workers from full pay to 80% and restricted the job-for-life guarantees that are demanded of most employers to companies with 10 or more workers, up from the previous threshold of three.

Schroeder, whose widowed mother raised him and four siblings by working as a charwoman after the father he never saw was killed in World War II, evokes her heroic struggle in the ashes of postwar Germany in denouncing the social security reforms imposed by Kohl.

“Especially burdened by these reductions is the generation of elderly women who lost their husbands in the war and were never afforded the luxury of a second income while they helped rebuild Germany and raised children on their own,” he says, noting that his own mother would have to get by on about $700 a month if not for his ability to support her. “I consider it rude for a country as rich as Germany to reduce pensions for this part of society.”

Sleight-of-Hand Plans

Asked how he would reverse those reductions while simultaneously investing in new jobs, Schroeder alludes to savings expected from a broad tax reform he plans later in his administration.

Such sleight-of-hand budgeting has armed Kohl supporters with credible claims that a Schroeder victory could further elevate taxes, and public squabbling within his own team has created an impression that the SPD, as the party is known by its German initials, isn’t sure itself what it stands for.

At a party rally in Duesseldorf last month, left-wing students heckled Schroeder and accused him of mimicking the Kohl government’s anti-foreigner policies to win over voters who blame high taxes and a poor job market on competition from immigrants.

On the right, Schroeder is suspect for his willingness to align with the environmentalist Greens party and possibly, although reluctantly, with the former Communists of the eastern states now calling themselves the Party for Democratic Socialism. Depending on how those leftist forces fare in the election--the Greens draw about 6% in polls and the PDS 4%--they could boost the 41% or so share that Schroeder’s party expects to win, thus enabling the parties to form a parliamentary majority and earn the right to name a chancellor and Cabinet.

The most likely outcome of the voting is that neither Schroeder’s party nor Kohl’s will gather an outright majority, creating an opportunity for the “grand coalition” of the two leading forces that is the preferred option of most Germans. Schroeder has made amenable noises, while Kohl rejects union with the SPD as an alliance that would require more compromise than voters might expect.

Ironically, Schroeder’s openness to cooperation with Kohl’s party could result in swifter and more painful reductions in the generous social security benefits he claims to want to protect. Without approval from the labor-oriented left, even a victorious Kohl might fail again to impose the belt-tightening needed to make Germany more competitive in the age of globalization.

Some Schroeder supporters have been telegraphing such a message.

“While Germany endlessly debates the shop-closing laws, the Internet revolution is going on beyond our borders,” 43-year-old software entrepreneur Jost Stollmann, Schroeder’s choice for economics minister, noted derisively during a recent campaign stop in Berlin. His disparaging of federal laws forbidding retail activities at night and on Sundays has angered the unionized bedrock of the SPD, but it probably appealed to younger voters.

While nonparty member Stollmann has been rattling supporters on the left, SPD Chairman Oskar Lafontaine has been equally problematic for Schroeder in the candidate’s efforts to woo the right.

A Doubtful Ally

Lafontaine, who failed to unseat Kohl in the unification-year election of 1990, has saddled Schroeder with much of the union-coddling policy in his platform and a contentious goal of phasing out nuclear power.

While Schroeder likes to present himself as the German version of Clinton or Blair, who brought their parties into a centrist mainstream from traditional blue-collar bastions, the unabashedly leftist Lafontaine remains firmly in control of SPD ideology.

Lafontaine is seen as the architect of Schroeder’s campaign strategy of running against a worn-out incumbent rather than against a defective platform. “The people just don’t want him anymore,” the party chairman said of Kohl, dismissing the incumbent’s chances of gaining strength from the newly improved job statistics.

With little that he can talk about to distinguish his quest for the chancellor’s post from that of Kohl, Schroeder has been careful to avoid outright besmirching of the incumbent’s legacy as the leader who presided over the reconciliation with East Germany and brought the united country into a bold new alliance with the rest of Europe.

“The main reproach one can make against Kohl is that he and his government are a spent force, unable to bundle the enormous creative powers existing in German society to take us into the next century,” Schroeder says of the incumbent, who is 14 years his senior. “That’s why I have invented the slogan: ‘Thank you, Helmut. But it’s been long enough.’ ”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.