Memo to Government: Think Common, not Special, Interest

After stalling in the recession of the early ‘90s, California’s economic engine is now in overdrive. From high-tech and biotech to entertainment and trade, the revival has been profound. Can we sustain this economic momentum? The answer may depend on how we deal with three critical issues: transportation, housing and education.

The former big three--tort reform, regulatory reform and tax policy--are still high priorities for the business community, but this year they have been overshadowed. This isn’t a special-interest agenda but a common-interest agenda that reflects the concerns and priorities shared by Californians.

Creating and maintaining jobs doesn’t just happen. It requires investment and entrepreneurial zeal, as well as a vibrant market. Most of all, it requires people with the ability to fill the jobs. California’s deficiencies in transportation, housing and education are the obstructions most likely to stall its economic engine.

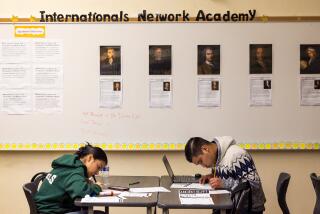

The plight of education has dominated the state’s political landscape for several years. From its postwar position of national leadership in education, our schools have become also-rans. The business community has supported efforts to upgrade education because it requires a trained and productive work force. This year, the California Chamber of Commerce actively supported Gov. Gray Davis’ proposals to increase school accountability, provide merit scholarships for top students in math and science, make Advanced Placement courses more available in high schools and address issues of teacher recruitment and retention. Recently released STAR test scores show California’s schools moving in the right direction.

But the crises in transportation and housing are entwined with improving schools. A livable commute and affordable housing are prerequisites for attracting and keeping productive workers. Hard-working men and women should be able to enjoy decent housing without spending hours stuck in gridlock.

During the ‘80s and ‘90s, highway travel increased at a rate 10 times greater than housing capacity. Four of the nation’s most congested bottlenecks are in Los Angeles and Orange County, and gridlock at these four interchanges, alone, is costing the motoring public more than $1 billion a year in fuel, repairs, environmental damage and lost time, according to a new study released by the American Highway Users Alliance. Traffic congestion isn’t just an inconvenience; it is an economic killer.

Though the problems of housing and traffic congestion are linked, the public-policy fixes are different. Cutting congestion requires greater public investment, along with streamlining the process for planning and building transportation projects. Affordable housing has less to do with an infusion of public money than with reducing the obstacles blocking development and forcing prices up.

Transportation emerged as the topic du jour in Sacramento this year. Senate President Pro Tem John Burton (D-San Francisco) started the trend last year when he proposed a constitutional amendment to allow voters to approve local transportation sales- and use-tax measures by a simple majority. Republicans in the Legislature came up with their own proposal to earmark the gasoline sales tax for transportation projects. The governor proposed a massive, project-oriented traffic-relief package that became the basis for an unprecedented $6.8-billion investment in transportation approved as part of this year’s budget.

As encouraging as this year’s focus on transportation is, the vital question of long-term funding remains. Numerous county sales taxes that support transportation projects--the major source of ongoing funding for local-transportation needs in most large counties--are due to expire. The priority for the governor and the Legislature must be to develop a sustainable, long-term program for funding highways and public transit. Since large capital investments and financing are involved, transportation doesn’t lend itself to year-by-year funding.

California’s prosperity not only has increased traffic congestion, but strong income growth and low unemployment also leave many residents struggling to find affordable housing. The California Department of Finance has estimated it takes between 230,000 and 250,000 new housing units a year to keep pace with population growth and household formation. For the past nine years, housing production has met only half that need. In 1998, Orange County created 61,000 new jobs but produced only 10,000 new housing units. Virtually everyone has heard a housing horror story like that of the accountant in South Pasadena with an annual income of $47,000 who makes less than half of what it takes to qualify for a median-priced home in the area.

The housing gap is caused by the cumulative impact of a number of factors. Fiscal chaos at the municipal level has turned land-use decisions into bidding wars that inevitably shortchange housing. Frivolous lawsuits have created an insurance drought that has virtually shut down construction of affordable condominium housing. And NIMBYs have blocked high-density, “in-fill” housing. A bipartisan group of legislators introduced a package of measures to curb abuses of environmental and liability laws, provide fiscal incentives for high-growth communities to approve housing, promote more efficient use of redevelopment housing funds and provide financial support to help low- and moderate-income families join the ranks of home ownership. While the governor and Legislature addressed some funding issues, real problems with land use and the resolution of construction-defects disputes remain.

Major improvements in education, housing and transportation each present a major challenge. But the business community’s approach to education offers a guide. Any business that neglected its worker-training programs, its delivery systems and its facilities would inevitably fail. The same holds true for the state.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.