Amid Nationwide Prosperity, ERs See a Growing Emergency

At the great hospitals of the nation’s major cities and ballooning suburbs, ambulances are being turned away and patients are stacked in hallways like so much cordwood. America’s dwindling capacity for emergency care is being outstripped by Americans’ demand for it.

And this time the victims are not just the poor, who have suffered for decades at the country’s cash-strapped public hospitals. This time the danger threatens almost anybody who suddenly takes ill or sustains a traumatic injury.

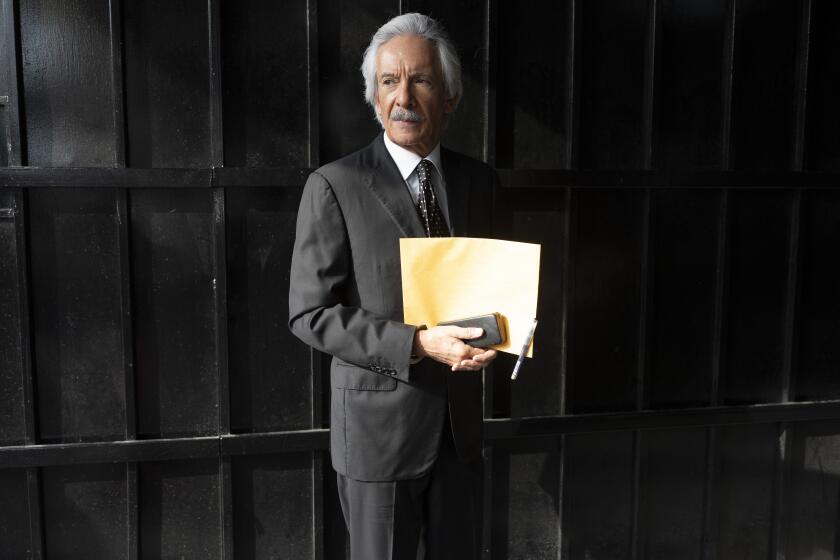

“Rich or poor, black or white, it doesn’t matter,” said Robert E. Maher Jr., who until recently was chief executive of Worcester Medical Center in Massachusetts. “The capacity simply isn’t out there anymore.”

Maher should know. When he had a heart attack in November while flying into Boston, he was turned away from the closest hospital, Massachusetts General, because of overcrowding and was forced to take an ambulance across town to find treatment.

The deterioration of the country’s emergency care system is a vivid example of the nation’s under-investment during the 1990s in the kinds of goods and services that traditionally have served as society’s foundation. It illustrates the peculiarly private nature of the decade’s long prosperity.

While affluent Americans spent richly on themselves during the 1990s, the nation as a whole devoted a historically small fraction of its expanding wealth to roads and airports, electrical generating capacity and basic medical services on which everyone relies.

One result is that the country is coming off its longest economic expansion in more than a century with fewer emergency rooms than it had to begin with. Accumulating evidence suggests that a second result is that the care being offered by many emergency rooms is worse, not better, than it was earlier in the decade.

Medical specialists generally agree that a key force behind the current crisis is an effort by business and government to let market forces streamline the nation’s huge and expensive health care system. This two-decade drive, which peaked in the mid-1990s, succeeded in moderating medical cost increases but at the expense of patient outrage and, now, ER breakdowns.

“We’ve increased the play of market forces in medicine, but medicine doesn’t lend itself well to markets,” said James J. Mongan, president of Mass General, one of the nation’s best hospitals.

“It’s taken some of the resilience out of hospitals and especially the emergency departments,” Mongan said. “It’s cut the reserves we used to be able to depend on.”

The signs of cutbacks are everywhere:

* Emergency rooms are declaring themselves overwhelmed and are shutting their doors to ambulances in spectacular and rising numbers. On average, the two dozen emergency rooms at the heart of Los Angeles County’s emergency system were closed more than one-fourth of the time in May and almost one-third of the time in June, according to the county’s Emergency Medical Services Agency. The figures are similar for surrounding counties.

Metropolitan Phoenix’s 29 emergency rooms simultaneously closed on eight occasions between January and April, according to Dr. Todd B. Taylor, an official with the Arizona College of Emergency Physicians. Metropolitan Cleveland’s 22 ERs were simultaneously shut for almost 10% of May, according to Cuyahoga County emergency services manager Murray A. Withrow. Simultaneous shutdowns set off a mad scramble among emergency officials to dole out patients to hospitals that already have said they can’t handle them.

* Hospitals are so full that ER doctors can’t find room for patients who need to be admitted. A new industry survey of 715 hospitals found that nearly half are running at 90% occupancy during peak periods, drastically higher than a decade ago. In a recent one-week period, metropolitan Boston’s 17 major hospitals reported operating at an almost unheard-of 96.2% occupancy rate. High occupancy rates leave no room for emergency arrivals, forcing ER doctors to park patients in hallway beds, sometimes for days at a time.

* For those not critically ill, the wait to see an ER doctor has grown so excruciatingly long that in at least five recent instances in Las Vegas, patients already at the hospital called 911 to be picked up by an ambulance and brought in on a stretcher in hopes of getting quicker care, according to Brian Rogers, managing director of Southwest Ambulance.

“It’s a crazy situation,” he said.

And, according to a wide array of doctors, administrators and policymakers, it is an increasingly dangerous situation for patients, even affluent and influential ones.

It certainly was for Nancy Ridley, who arrived at the Lahey Clinic in Burlington, north of Boston, on Mother’s Day with a spiking fever and painful cough. She had to wait almost eight hours to be admitted with pneumonia. Ridley, as it happens, is the state’s assistant commissioner for public health.

A recent review of government regulatory files found that nearly 10% of the country’s ERs were cited for failing to provide adequate care to all comers from 1997 through 1999, and documents from California suggest there has been no improvement in the 18 months since.

“The breakdown of the emergency room is the single most important public health issue facing middle-class and affluent Americans today,” said Stuart H. Altman, a veteran health policy analyst and co-chairman of a Massachusetts task force assigned to figure out what to do about the problem.

“I struggle with this question,” lamented Dr. Arthur Kellermann, chairman of emergency medicine at Emory University medical school in Atlanta. “How can we spend such an astronomical amount of money on health care and still not have enough emergency rooms?”

No Simple Answer

Answers to Kellermann’s question are myriad. Managed care companies have cut reimbursements too much. The ranks of the uninsured, who rely heavily on ERs, are swelling. Americans are getting older and sicker. There is a severe shortage of nurses.

However, some policymakers and a great many emergency room physicians are beginning to believe that the fundamental answer lies with the increasing play of market forces in medicine.

Starting in the 1970s, but most dramatically since Congress in the early 1990s rejected then-President Clinton’s plan to overhaul the nation’s health care system, the country has relied ever more heavily on the private sector rather than on government regulation to decide how the medical care system should work.

As with other deregulated industries, such as telephones and airlines, the unleashing of private-sector forces has produced some striking positives. It has spurred speedy adoption of technology, such as the CT scan, encouraged use of less-expensive outpatient treatments and, at least until recently, helped slow the growth of the nation’s health care bill.

“The free market mechanisms we’ve adopted make sure we contain costs, fully utilize resources and hit our financial targets,” said Dr. Michael L. McManus, associate director of intensive care at Children’s Hospital in Boston and the author of a new study of ER overcrowding in Massachusetts.

But, according to McManus and others, there has been a troubling downside. The same mechanisms, he said, “have squeezed out the extra resources we need to take care of the kinds of medical surprises that come into emergency rooms every day of the year.”

Money-losing ERs are a low priority for profit-driven hospitals. Dr. Daniel Higgins, ER director at St. Francis Medical Center in southeast Los Angeles, said that, in the process of making medicine more businesslike, “we’ve forgotten that emergency rooms are the safety net for the country.”

A ‘Management Tool’

The most glaring symptom of the emergency care crisis is the sudden rise in the practice of hospitals’ closing their crowded ERs to ambulance patients, diverting them elsewhere.

Diversions rarely occurred until a few years ago, according to Virginia P. Hastings, director of L.A. County’s EMS agency. Now “they’ve become a regular management tool.”

And their use is not limited to cash-strapped public hospitals; they are just as heavily employed by some of the nation’s most prestigious and well-endowed facilities.

In Los Angeles, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center turned away ambulances more than 40% of the time in June, according to Hastings’ agency. In the same month, UCLA Medical Center warned them off almost 25% of the time, EMS agency records show.

In Boston, where emergency room woes were first documented by the Boston Globe, Mass General’s ER was shut to ambulance patients almost 12% of the time last year, twice as often as any other hospital in the area. Likewise, the Cleveland Clinic was on diversion nearly half of last year.

Hospital and EMS officials are quick to point out that just because an emergency room is on diversion does not mean it is not receiving patients. Under federal law, people who get to the hospital without an ambulance must be seen, eventually. In addition, if enough facilities go on diversion at the same time, rules in most states and localities allow ambulance crews to deliver patients to hospitals whether the hospitals want them or not.

But officials concede that emergency room overcrowding is not solved by the law or the rules. Indeed, they may contribute to it by discouraging some sick people from using ambulances in favor of getting themselves to the ER.

In one recent instance, a Fresno man suffering chest pains was on the way to the local hospital in an ambulance when he was told that the hospital and two other medical centers in the area were on diversion, according to county EMS administrator Daniel J. Lynch. Lynch said the man demanded to be taken home. He then got in his car and tried to drive himself to the first hospital. Paramedics luckily found the man’s son in time for him to do the driving.

“We don’t want people having heart attacks driving around on the roads,” Lynch said.

More important, ER doctors and state and local officials warn, ambulance diversions are raising the risk that patients will end up being delivered to the wrong hospital at the wrong time.

In Massachusetts, state officials are investigating two cases in which diversion is suspected as contributing to patients’ deaths.

Last fall, a 55-year-old Cambridge woman suffering chest pains sought to be taken to a hospital where she had just been treated for a heart attack. But, according to a state investigative file, the hospital’s ER was overcrowded, and the ambulance carrying her was turned away.

Mass General’s ER also turned her away, and the woman ended up at a third facility, which was not equipped to provide advanced cardiac treatment. By the time doctors there realized what the patient needed and sought to have her transferred to the first hospital, it was too late. She died. None of the three hospitals involved in the case would comment for this story.

In the Cleveland suburb of Parma, relatives of Rob Balodis believe he was the victim of a similarly fatal round of miscalls and delay.

Balodis’ mother, Nora, conceded in an interview that the 40-year-old unemployed bartender had a number of strikes against him. He was an alcoholic who suffered from cirrhosis of the liver and periodically hemorrhaged.

But she said his prospects were not improved when the ambulance carrying him to MetroHealth Medical Center, a large public hospital with specialists who could have helped, was diverted because of emergency room overcrowding and he ended up at Parma Community General Hospital, which did not have the specialists he needed.

“The [Parma] doctors asked me, ‘Why is he here?’ ” remembered Balodis, a retired telephone company employee. “They said, ‘Well, we really can’t help.’ ”

Balodis died 15 hours after arriving at Parma, leaving an 8-year-old daughter. MetroHealth and Parma officials refused to comment.

Problem Shifted Gears

What is especially vexing to medical specialists is that the current crisis comes not just after a long period of prosperity but after several years in which it appeared that the nation’s ER problems were on the verge of a solution. Now there is a fierce debate about what is behind the backsliding and who is to blame.

As recently as the start of the 1990s, the seemingly insurmountable problem at most ERs was too many people arriving with too few means to pay.

While the payment problem has not improved--especially in places like Southern California, where immigration has pushed the portion of the population without health insurance above 25%--overcrowding suddenly began to ease in the middle of the decade.

To the surprise of most health care specialists, the number of people visiting emergency rooms fell from 1993 through 1994 and again from 1995 through 1997, as managed care companies discouraged ER use by refusing to pay for most visits. Although ER visits have resumed their upward climb, many analysts say the increase is not enough to explain today’s troubles.

What does explain it, and what distinguishes the current crisis from those of the past, is the extraordinary difficulty that ER doctors have getting sick patients out of the emergency room and into the hospital.

Almost everyone agrees that the immediate cause of this problem is a huge drop in the number of intensive care unit beds at U.S. hospitals. Figures from the American Hospital Assn. show that the nation shed more than 17% of its intensive care unit beds from 1990 to 1999, the last year for which figures are available.

There is no such agreement about why so many beds were lost.

The hospital industry blames the nursing shortage. The AHA recently issued a survey that found that 126,000 nursing slots were vacant at U.S. hospitals for lack of qualified candidates.

“If the issue was just physical beds, the problem could be solved in no time,” said Carmela S. Coyle, the hospital association’s senior vice president for policy. “The issue is, do we have the adequate human resources to staff those beds? And we don’t.”

But industry critics counter that hospitals have closed expensive ICU beds to cut costs and devote more resources to lucrative, easier-to-manage elective surgery patients. They call the shortage an entirely predictable byproduct of the financial incentives at work in today’s health care marketplace.

“In a market-based system, the sensible thing for a hospital is to fully utilize its resources by filling as many beds as possible,” said McManus, the Boston intensive care director.

“The problem is that when a hospital does that, where do you put the emergency patients?”

Time Ran Out for One

Whoever wins the bed debate, it will be of little consequence to a 65-year-old woman who showed up at the Community Hospital of San Bernardino on a Sunday afternoon late in October complaining of chills and dizziness.

It took the emergency room nurse an hour and 40 minutes to see the woman, according to hospital records cited in a federal investigation of the incident. The nurse then labeled the case urgent but was told there were no beds in which to hospitalize the woman. So the woman was sent back to the waiting room.

It wasn’t until the woman’s daughter told nurses, “The patient’s tongue is sticking out,” that she was seen again, according to the records. But by then, she was in the early stages of what proved to be a fatal heart attack. A hospital spokeswoman refused to comment.

Most government and medical leaders concede that the repairs they are making to emergency care systems around the country are little more than stopgap measures. Many say it will take a galvanizing event, such as the death of a celebrity, to bring about changes.

In Boston, Mass General is adding a handful of intensive care unit beds while the state launches a Web site to let doctors and paramedics know which emergency rooms are diverting ambulances and when, according to Dr. Howard K. Koh, Massachusetts’ public health commissioner.

In Cleveland, Cuyahoga County officials recently tinkered with their policy for distributing patients when hospitals are on diversion. It was the sixth time they had changed the rules in two years.

In Los Angeles, emergency medical officials hope to win one-third of the $25 million that the state recently approved for trauma centers, the ERs that specialize in the most extreme cases. But even that may not be enough to save all 13 of the financially troubled facilities.

Ultimately, said Jim Lott, executive vice president of the Health Care Assn. of Southern California, a hospital trade group, two of the 13 are likely to close. If they do, he said, Angelenos may be in for a big surprise.

“It will all depend on where you have your car crash or heart attack whether you get the treatment you need or not,” Lott said. “It won’t matter one bit how much money you’ve got in your wallet or who you know, just where you are.”

And how far it is to the nearest emergency room.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.