Unique Court for Sex Crime Victims

Inside the courtroom, jury selection is underway, and one member of the pool, a nurse, starts sobbing. She can’t go through with it, she says.

“I was sexually abused myself,” the woman in her 50s explains, her voice quavering. “I was 12.” The prospect of having those awful memories dredged up, she says, is too much to bear.

At the outset, prosecutor Jalal Harb has put the 40 potential jurors on their guard. “In testimony, there is going to be some mention of sexual organs,” warns the assistant state attorney. “You going to have any problem going back to the jury room to discuss that? And what about pictures? Can you handle pictures?”

Some others summoned for jury duty admit to being too squeamish, prejudiced or outraged to be fair. Ultimately, the pool is pared to four men and four women. They will be paid $15 a day.

Division H of the Hillsborough Circuit Court, America’s only court dedicated solely to sexual offenses and child abuse and neglect cases, is ready to go into session.

“What you’re going to be hearing for the next day and a half or so is not pretty,” Assistant Public Defender Ursula Richardson tells jurors in her opening remarks. “You’re not going to like it.”

No criminal matters, legal experts say, put the justice system and its adversarial court proceedings to the test like sexual offenses: rape, lewd and lascivious behavior, child abuse. Often there is no hard evidence, just the word of one person against another. Frequently, the victims are children, torn between telling the truth and shielding a loved one.

Tampa’s sex court is an attempt to be more humane in the quest for justice and punishment, as well as more efficient. The presiding judge is a former sex crimes prosecutor. Both the state attorney’s and public defender’s offices have staff members who specialize in the offenses tried in Courtroom H.

The goal is justice but also a better guarantee that victims, often profoundly damaged by the crimes committed, aren’t victimized yet again by the system.

On this particular week’s docket is a violent case, the state of Florida vs. Sorrell Eugene Huff. On Jan. 21, the state charges, Huff savagely beat, stabbed, raped and sodomized at gunpoint the 18-year-old daughter of his live-in girlfriend.

He allegedly gagged and hogtied the teen, dumped her in a closet, left to meet his 40-year-old girlfriend at her job, then beat and tried to kill the second woman with a butcher knife. The defendant faces nine felony counts, including sexual battery, armed kidnapping, aggravated battery, aggravated assault and attempted murder.

Clad in a light-brown jacket and dark tie, Huff, 31, is smiling, chatty as he enters the courtroom. He has pleaded not guilty and wants to testify “to try to vindicate me of these devious charges.”

Judge Jack E. Espinosa Jr., 46, is calm and even-keeled, with a passion for baseball and a sense of humor that leans toward Groucho Marx. His job, he says, forces him to confront society’s darkest secrets.

During jury selection, Espinosa says, sometimes as much as a third of those in the pool confess to having been sexually abused as children or having a relative who was.

“You get so involved with the legalities and issues, you sometimes lose sight of what people are hoping for when they get into these trials,” the judge says. “Sometimes, it’s simple recognition that what they said happened actually did.”

At home, Espinosa keeps a card sent by a little girl who had been molested by a neighbor. Tears come to the judge’s eyes when he repeats its inscription: “God please let the jury believe what I said. Because it was true.”

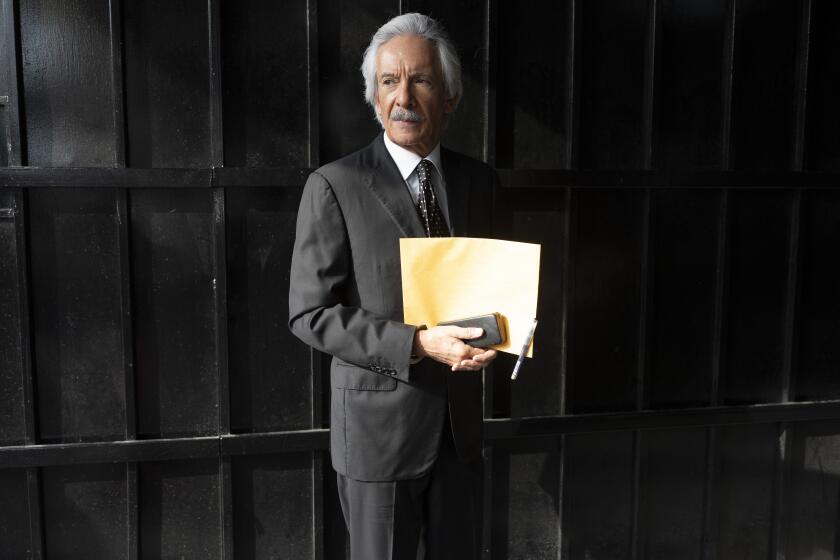

The intimate circumstances of many sexual offenses often make it especially difficult to prove what transpired. “Honestly, I think this is one of the hardest specialties in the law,” says prosecutor Harb, 44. “You’re trying to constantly determine: Did this happen? You navigate issues like divorce, child support, visitation rights, trying to figure out what the truth is.”

In instances where there are no third-party witnesses or physical evidence, the victim and alleged perpetrator each give a version of events, “and clearly whoever can narrate the story better wins,” Harb says.

Prosecutors often opt to plea-bargain rather than go to trial, to spare victims the ordeal of appearing in court.

“Compare a rape with say, a robbery,” says Barbara Baldini, a former Bronx district attorney who is the lead writer of a four-volume handbook on prosecuting sex offenses. “Both could be very frightening to the victims.

“But the difference is that with a robbery you don’t go in to the police with a sense of shame and humiliation, with the sense ‘this was my fault.’ ”

As often as not, the perpetrator goes unpunished. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, there were 72,809 rapes reported nationwide in 1999; arrests were made in 49.5% of the cases. Moreover, a 1992 study estimated that only 16% of all rapes are reported.

In large part to make the legal process less traumatic for victims, Hillsborough County last year inaugurated its groundbreaking sex court.

Matters now heard in Tampa’s Division H used to be spread throughout five other divisions. “Before, our prosecutors were running from courtroom to courtroom to cover these cases,” says Karen Stanley, chief assistant in Florida’s state attorney’s office.

Since the court’s creation, prosecutors say, 93 sexual assault cases have been adjudicated and have resulted in 85 convictions through trials or plea-bargains--a 91.4% conviction rate.

Laws in Florida concerning sex crimes are often different from those governing other crimes, a rationale for having a separate court. State lawmakers have tried to protect minors 11 and younger by sometimes allowing their hearsay testimony, for instance, letting adults repeat what children told them.

(On the second floor of the Tampa courthouse, a suite of rooms has been outfitted for the youngest victims, complete with artificial palm tree and rainbow-colored tropical fish murals. Behind a two-way mirror, a TV camera is concealed. Children can testify here via closed-circuit link if prosecution and defense attorneys agree.)

Also, evidence of a defendant’s repeated sexual offenses may be admissible in Florida courts. And victims are protected by Florida’s “rape shield” statute, which generally bars the defense from prying into their sexual history.

By the time Florida vs. Huff begins, bailiffs are well aware of the defendant’s history. Huff has been arrested 24 times, and they aren’t taking chances.

Each day, the 5-foot-9, 250-pound man with the shaved head is brought to the courtroom in manacles and leg irons.

That Huff’s trial is taking place six months after the alleged offenses is one of the most eloquent arguments in favor of the Tampa court. Usually, 1 1/2 to two years elapse before a rape case goes to court in the United States, Baldini says. In Los Angeles, the average time is nine months.

Under oath, Huff admits to beating the 18-year-old but says their sex was consensual. When called to testify, the young woman is composed, articulate. In the attack, her left cheek was slashed, her left upper jaw, cheekbone and eye socket fractured, her upper palate split. She needed two months of surgery and hospital care. Jurors stand to look at the rope burns left when Huff allegedly tied her up.

“He gave me three choices,” she testifies. “A. He could kill me. B. He could paralyze me from the neck down. Or C. I could have sex with him. And I chose A.”

The mother, like Huff, has numerous felony convictions. She says her ex-boyfriend stabbed her twice in the torso and struck her repeatedly in the face.

“He kept saying, ‘I’m going to kill you this time,’ ” she says.

A semen sample taken from the daughter was analyzed for DNA. Kelly Carter, a crime lab analyst from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, testifies that in 12 of 13 areas, the specimen is identical to Huff’s DNA. It’s a “1 in 474 quadrillion” match, she says.

Another prosecution witness, a forensic nurse, testifies that the teen’s injuries are not consistent with consensual sex.

Jurors are out for six hours. They reject the charges related to the gun and knife, including the attempted murder charge, but convict Huff of rape, kidnapping, aggravated battery and assault.

The next morning, the defendant is sentenced to a life term.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.