U.S. Lawman’s Trip to ‘Heart of Darkness’

After three decades in the courtroom trenches, from California to Washington to Europe, Mark Harmon has seen his share of crime scenes.

None comes close, however, to the landscape of death the senior war crimes prosecutor visited in Bosnia-Herzegovina two years ago as he prepared for his latest case: the slaughter of more than 7,000 Muslim men and boys in the town of Srebrenica in 1995.

Escorted by an armed column of U.S. combat troops, Harmon saw vast clandestine graves, piles of skulls wearing tattered blindfolds, execution chambers that were macabre mosaics of bullet holes, blood and flesh. In the hills of eastern Bosnia, he heard echoes of Auschwitz, Cambodia, Rwanda--all the places where the industry of murder went into mass production.

“You are in the heart of darkness,” Harmon said. “You sense it. It’s palpable.”

This month, a polyglot law enforcement team led by the Californian won a precedent-setting victory when a three-judge panel of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia convicted a former Bosnian Serb general of genocide for the massacre of Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica.

The 46-year sentence handed down to Radislav Krstic was the finale to an international detective story featuring extraordinary contributions by U.S. intelligence agencies, a cerebral French sleuth and a supporting cast of anthropologists, archeologists and pathologists.

For the prosecutors, the case was an obsessive odyssey. If investigators are haunted by a sole murder victim, imagine multiplying the emotional toll by thousands. There was the foul work of digging up graves, sifting through remains, reconstructing the unthinkable. There was the survivor who described lying in a field at the feet of the executioners, wounded, half-crazed by thirst and wishing he were one of the corpses that surrounded him.

“I was sort of between life and death,” testified the Bosnian Muslim, who was designated Witness O. “I didn’t know whether I wanted to live or die anymore. I decided not to call out for them to come to shoot and kill me, but I was sort of praying to God that they’d come and kill me.”

That is one of the voices that Harmon, a 56-year-old native of Burlingame and a former public defender in Santa Clara County, carries with him now. He is tired, but he is proud of having established what he calls “the single most complete objective record” of the Srebrenica massacre, the worst atrocity in a 1992-95 war marked by brutal “ethnic cleansing.”

In solemn, measured tones, he expresses disgust with continuing denials by hard-line Bosnian Serbs, such as a high-ranking military official who testified for the defense, that the carnage ever took place.

“The authors of this crime cast a stain on the reputation of Bosnian Serbs, and, unfortunately, the way to remove that stain is to identify the culprits and show that it wasn’t collectively the Bosnian Serbs but individuals,” Harmon said. “But as long as you have witnesses like this who say it never happened . . . you are never going to contribute to any greater reconciliation of Bosnia.”

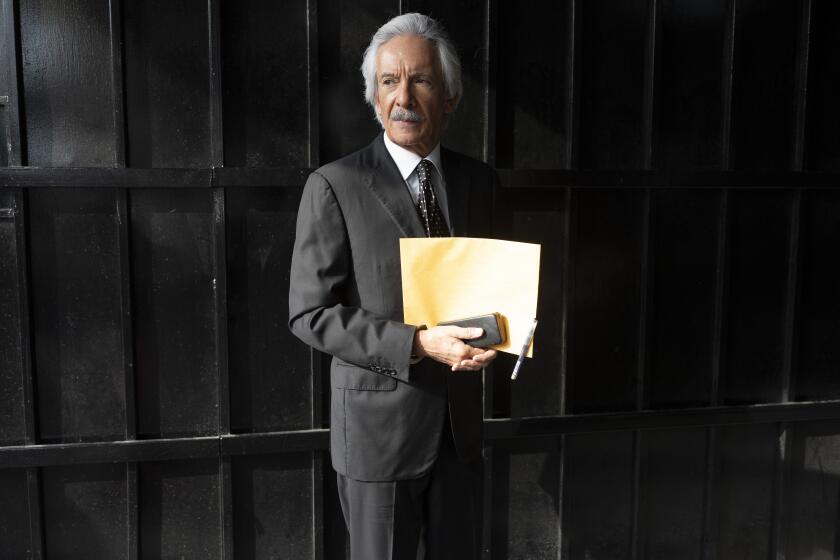

In the halls of an international court filled with a spectrum of ethnicities and a babble of languages, Harmon can be spotted in a second as the quintessential U.S. lawman: graying helmet of hair, strong, brooding features, a solid frame in a striped shirt and dark blazer. His three fellow prosecutors in the Krstic case were American, British and Australian.

“This case was very strong, and the evidence was very substantial,” said a Western official involved in the case. “These guys are classic prosecutors. When they get involved in a case, there’s only one thing in the world for them, and that’s their case. They were very tenacious and creative in the way they went about building it.”

Harmon and two other American prosecutors at The Hague share a California connection. After graduating from the Hastings College of Law in San Francisco, Harmon became a public defender in Santa Clara County. Two lawyers he met there now work with him in The Hague.

Peter McCloskey, another Krstic prosecutor, once argued cases against Harmon as a deputy district attorney. Alan W. Tieger, also a prosecutor at the international court, worked with Harmon as a Santa Clara public defender.

All three eventually moved east to the U.S. Justice Department’s civil rights division, which investigates brutality and corruption by law enforcement. The switch wasn’t difficult, Harmon said, because 12 years of representing low-income defendants had educated him about misdeeds by people in uniform.

While locking up Ku Klux Klansmen and abusive cops, Harmon displayed a rebellious streak in Washington. He sued his employer--the Justice Department--over a decision to administer mandatory random drug tests to employees. It was a matter of principle, Harmon said. With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, the lawsuit prevailed.

“There was a certain climate of uncertainty about what would be the consequences to suing your boss,” he said wryly. “But I can say, to the department’s great credit, there were no consequences.”

In 1994, Harmon ran into his old friend Tieger on a street corner. Tieger had recently completed the trial on civil rights charges of four Los Angeles Police Department officers involved in the beating of Rodney G. King, two of whom were convicted. Tieger was on his way to the Netherlands to start work at the United Nations’ newly created court trying war crimes committed in the former Yugoslav federation.

“I said, ‘Gee, that’s the ideal job,’ ” Harmon recalled. “I had grown up always in great admiration and respect for the trials at Nuremberg. Those images from World War II had always haunted me.”

The deadline for applications had passed, but Harmon typed up and sent a resume and was hired. He moved his wife and three children to The Hague.

The court lacked resources in the early days. Intent on results, the founders made some ill-advised decisions, expending effort on low-ranking suspects and relatively weak cases, according to critics. Over time, the court has gained respect, racking up more than 100 indictments and about two dozen convictions.

The Krstic case is regarded as exemplary. The prosecutors gained cooperation from Washington. U.S. troops with the NATO-led peacekeeping force in Bosnia arrested Krstic and provided an expert witness who explained in detail how the highly organized slaughter had to have involved top commanders.

Moreover, U.S. intelligence agencies provided unusual assistance. After ensuring the protection of sources and secrets, intelligence officials turned over jealously guarded treasure from their high-tech vaults: 100 aerial surveillance images that pinpointed the likely locations of killing fields, mass burial sites and secondary sites where corpses were reburied as part of a cover-up.

The aerial photos were decisive corroboration for a jigsaw puzzle of evidence that included seized military documents, testimony of witnesses and a repentant triggerman, radio intercepts by the Bosnian Muslim military, forensic clues and even fuel records for bulldozers.

Describing the investigation of the slayings of 1,200 men and boys at a military compound, Harmon said intelligence photos captured bulldozers digging a communal grave.

“You can see the bodies and the earthmoving equipment,” he said. “We had the image, so we knew where to dig. We did a probe, did forensics, we conducted an exhumation. Of course there were bodies, just as the victims had said. We had compelling evidence that a crime had taken place.”

On the ground, the lead bloodhound was Jean Rene Ruez, a veteran of the French judicial police and chief of 10 investigators representing as many nationalities.

An edgy, animated man who gestured while he talked, the relentless Ruez won over U.S. intelligence officials who, according to the Western official involved in the case, were initially skeptical about working with him. A French general had been prominent among the U.N. officials accused of failing to stop the atrocities.

Of Ruez, who retired from the tribunal recently because of the toll the Srebrenica case took on him and his family, Harmon said: “He was extremely bright, a gifted investigator. He was obsessed with preparing a very good case.”

As were they all. And Harmon hasn’t had much time to savor their triumph. Unlike most of the people in Europe, he will not take a vacation this August. He is preparing for the trial of two senior Bosnian Serb political leaders, a case that could be expanded to target Bosnian Serb strongman Radovan Karadzic, one of the court’s top fugitives.

There have been recent rumblings that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization is gearing up for a capture of Karadzic and Ratko Mladic, his former armed forces chief and the accused mastermind of the Srebrenica massacre.

It’s not surprising that Harmon’s work has caused him to reflect on the nature of evil. He said he believes that genocide requires two types of criminals: those who actually enjoy killing and those who don’t have the moral courage to resist heinous orders.

With its relatively moderate sentence, the court appears to have concluded that Krstic was a moral coward rather than a savage.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.