Economy Rooted in Factory Plants

California is renowned as a hotbed of creativity and design. But its future in the new economy might well depend on retaining its traditional expertise in manufacturing, said a report released Thursday by the Santa Monica-based Milken Institute that examines the economic role of the industrial sector.

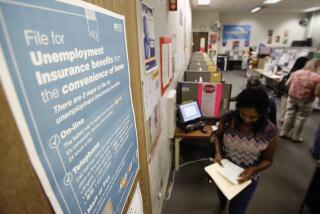

By far the nation’s largest manufacturing state, California is home to industries that employ more than 1.8 million people. Yet the Golden State, like the rest of the country, is fighting the perception that waning factory jobs are the inevitable byproduct of a high-tech era.

The reality is that one cannot exist without the other, said Milken economist Ross DeVol, who is trying to debunk the notion that a place such as Silicon Valley can continue to thrive on bright ideas alone.

Much of the wealth created in California from the technology revolution has come not just from the invention and design of computers, software and other high-tech products but from the manufacture and export of these tangible goods. Gross state product generated by California’s high-tech manufacturing was $131 billion in 2001; computers and electronic products accounted for about half of the state’s exports last year.

Manufacturing is inexorably linked to innovation and thus critical to the ongoing vitality of any high-tech center, DeVol said. The report notes that Silicon Valley’s greatest technical innovation--the microprocessor--was the result of a manufacturing improvement, setting the stage for the knowledge-based economy the Bay Area knows today.

“To remain on the leading edge, [California] must produce things, not just design them,” said DeVol, the Milken Institute’s director of regional and demographic studies. “But we’re at risk of losing our edge.”

Since May 2000, California has shed more than 115,000 manufacturing jobs, many of them in the lucrative technology sector. Although some of these jobs will return when the tech sector rebounds, others won’t because of structural changes in the industry. Stung by falling profits and unlikely to see revenue rebound to the frenzied levels of the late ‘90s any time soon, high-tech manufacturers such as Milpitas, Calif.-based contract manufacturer Solectron Corp. are cutting jobs here while expanding operations offshore.

The state faces huge challenges in retaining high-tech production as well as other types of manufacturing, said Jack Stewart, president of the California Manufacturers and Technology Assn., which funded the Milken study. The state’s business costs are among the highest in the nation. California’s tax structure motivates sales-tax hungry communities to favor big-box retailers and car dealerships over factories. And the state’s anti-business image hasn’t helped matters. Companies that once viewed a California address as a sign of success are expanding elsewhere. Santa Clara, Calif.-based Intel Corp., for example, hasn’t built a factory in the state since the late 1980s.

The stakes are high. According to the Milken study, California’s average manufacturing wage and salary income was $54,600 in 2000--among the highest in the nation. Because of manufacturing’s high multiplier effect, every time a factory job is lost in California, an additional 2.5 jobs are lost in other sectors that supplied goods and services to the plants and their employees. Manufacturing exports account for 9.4% of California’s gross state product, and manufacturing jobs have long provided immigrants and minorities with a springboard into the middle class.

Although DeVol acknowledged that California will never become the lowest-cost location to put a factory, he said there are a number of things that policymakers can do to make the state more attractive to manufacturers, from lowering some business taxes to streamlining regulations and the like.

But he said the biggest challenge may be educating lawmakers that California’s rise in the new economy has its roots firmly on the factory floor.

“People forget that Silicon Valley is still largely about manufacturing,” DeVol said.