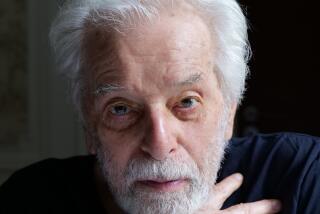

To director, it’s got to feel real

Director Charles Stone III’s career trajectory has produced a trio of strikingly dissimilar works: (1) Budweiser’s “Whassup?” TV commercials, (2) a feature film about the rise of three ‘80s cocaine kingpins in Harlem, and (3) a forthcoming look at the flamboyant sub-subculture of college marching band drum corps.

Just shows you what can happen when your mom takes you to fencing and pottery lessons and museums, your dad quotes inspiring literature around the house and you fall in love with classic Warner Bros. animation, “The 7th Voyage of Sinbad” and “Star Wars.”

Stone, 36, still best known for writing, directing and acting in those Bud commercials, which thrust a slang expression into the heart of mainstream culture in 2000, will enjoy his major-league taste of the cinema spotlight Friday when Fox releases “Drumline,” a drama of competition and redemption set at fictional Atlanta A&T;, a historically black college.

Stone, who spent most of his 20s directing music videos, has no trouble connecting the dots between “Drumline,” the Bud spots and the surprisingly sensitive dope-dealer film “Paid in Full,” which was released by Miramax’s Dimension Films in only a few hundred theaters in October and quickly disappeared.

“Real people,” he said in a phone interview from his home in Brooklyn. “Realistic people that are approachable to the viewer.”

Stone’s Bud spots, which won a slew of advertising awards, grew out of a two-minute short film called “True” that he made for $1,000 in a day and a half in 1998 with some old friends from Philadelphia, where he grew up. The film, which he hoped would be his ticket to feature film directing, found its humor in the unspoken bonds within the greeting “Whassup?” -- and the answer: “Just chillin’.” It played well at a music video association short-film festival in L.A., winning Stone an agent and a number of directing offers, including “Paid in Full.”

Coincidentally, a copy of “True” fell into the hands of a Chicago ad agency retained by Budweiser, which signed up Stone to translate the short into a series of commercials. (“Whassup?” “Watchin’ the game. Havin’ a Bud.”) After auditioning scores of actors, the agency agreed to let Stone and his pals play the roles.

The spots were not only funny (in one, a patron of a Japanese restaurant verbally stretches his pronunciation of the condiment wasabi until it is indistinguishable from “Whassup”), but also transcendent: An African American catch phrase was demystified to illustrate the way friends of all cultures--particularly male friends, and even more particularly male sports-buff friends--are able to communicate in the simplest of expressions.

“It’s two guys on the telephone who appear to be talking about nothing but, if you will, are holding hands,” Stone said. The focus is on “the grunts and nods and between words, some of those little idiosyncrasies, the funny details about being human.”

By spring 2000, the “Whassup” spots were being parodied in every medium, creating the kind of buzz advertisers dream of. Stone was trying to move on in his career but was continually greeted by strangers asking him the inevitable rhetorical question. (After he shaved his beard last year, he said, it seemed to abate.)

The little-noticed “Paid in Full,” a fictional account based on the lives of three actual hustlers, is littered with nuanced moments that distinguish it from other films about the way cocaine tore apart poor communities in the ‘80s. Ace, the straight-arrow protagonist who makes deliveries for a dry-cleaning business, is pulled slowly against his nature into the drug trade. By the end he is the boss, soberly watching his two pals make $10,000 bets at the kitchen table on whether they can throw a crumpled wrapper into a trash can.

Talking about the film, Stone is drawn to a scene in which one of the now-wealthy kingpins, Mitch, who is enamored of neighborhood recognition, comes home at night and meticulously folds his clothes and lays his gold jewelry across them before getting into bed, stripped of his trappings. “That shows the character without saying a word. We need to be able to sit there and just take it in,” Stone said. Later on, Mitch boasts to Ace that his prominence as a dealer makes him feel the way Magic Johnson or Larry Bird must feel on the basketball court, when all eyes are on him.

There are fewer opportunities for intimacies like that in the wide-release “Drumline,” an energetic story of conflict between a gifted but undisciplined New York-bred freshman drummer and the Atlanta A&T; senior marching band leader determined to mold him. Stone said he was drawn to the script’s emphasis on the tradition of marching band halftime shows at black Southern colleges, where the military-style flavor is replaced by a more athletic, can-you-top-this sensibility. He said he aimed for a “ ‘Top Gun’ with drums” feel, “a Bruckheimer muscularity ... a sports movie.”

Within that brashness, one subtlety Stone relishes occurs when the freshman, Devon, played by Nick Cannon, is on the phone to his mother, telling her he’s made first-string drum line. Their affection and the generation gap between them are illustrated simultaneously. “I just called to tell you that everything is everything,” Devon says near the end of the call. The camera shows him listening, then saying: “Oh, come on now, you know what that means: ‘It’s all good.’ ”

Producer Wendy Finerman said she offered “Drumline” to Stone after she saw a cut of “Paid in Full.” “The fact that the ‘Whassup?’ spots and ‘Paid in Full’ came from the same talent was startling to me,” she said.

The film, with a $20-million budget, was more than three times as expensive as “Paid in Full” and will debut on about 1,800 screens. Both films presented Stone with the challenge of telling another writer’s story--in the case of “Drumline,” a script by Tina Gordon Chism and Shawn Schepps, based on a story by Schepps. Stone says he is currently sifting through scripts but has his heart set on directing a work of his own --”creating a film from the seed of an idea and developing it into the tree ... I haven’t been able to do that fully yet, in the sense of really letting the dialogue be as poetic or lyrical as it is in ‘True.’ ”

He describes himself as a once-hyperactive child who benefited from myriad influences. His father, journalist Chuck Stone, was one of the first black columnists to appear in a major white-owned newspaper. The son’s talents were in the visual realm. He didn’t like to read but fell in love with the illustrated covers of sci-fi books. When he was 10 or 11, he said, he saw “Star Wars” and his ambitions fell into place. “That just upped the ante on me making that journey into the world, it really fired me up. I would tell people, ‘I’m going to be a special-effects supervisor and animator like John Dykstra or Richard Edlund.’ ”

He played junior high football because wearing the gear made him feel like a warrior. He studied animation at Rhode Island School of Design, where he messed around playing drums and doing stand-up comedy on amateur nights, then broke into hip-hop music videos after graduation. “I figured I would go to New York, move to music videos, maybe short films, then feature films. I had it all planned.” Within the planning came the surprise of directing TV commercials, and here Stone was lucky: He hooked up with advertising agency executives who, while white, did not try to homogenize the Bud spots, preserving their genuineness.

Stone, who is single, lives in Clinton Hill, a gentrified section of Brooklyn. He has no plans to move to Hollywood; he’s reluctant to give up the creative moments that come from hanging with friends or riding on subway or commuter trains. He says he is trying to slow the pace of recent years and is contemplating his future. He’s sure he’ll make a comedy someday. And he’s sure he’ll make a film “with spaceships and laser beams.” Whatever he does, he pledges, will be “the human journey ... whether it’s the year 4028 or the football field.”

He also says he has a debt to pay to a beloved arts teacher at Central High in Philadelphia, whom he described as yet another inspiring force. “At some point, I have to go back and teach; I am so compelled to go back and affect somebody like I was.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.