Battle in a Time of Peace

A crowd gathers at a dusty outdoor social center in the Morro Bento neighborhood here to watch as a young man tries to persuade a teenage prostitute to have sex with him--without using a condom.

The man offers to pay double, arguing that using the contraceptive will ruin his fun. But the sex worker stands firm, finally convincing her prospective customer that using a condom properly can actually enhance his pleasure, because it can prevent his death.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. July 11, 2002 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Thursday July 11, 2002 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 21 inches; 763 words Type of Material: Correction

Angola’s population--A Sunday story in Section A about AIDS in Angola incorrectly reported the country’s population. The correct number is about 12 million.

The children and adults who have congregated to watch the seven-minute skit join in as the couple sing the joys of safe sex.

“I think it is the right way to teach people about HIV and AIDS because it’s easy for people to learn,” said Nati Florinda Camoss, 22, who brought her two young daughters along to watch the amateur theater performance.

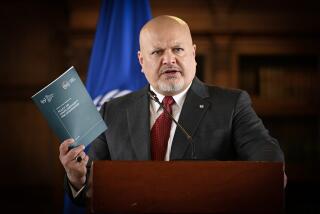

That’s exactly what representatives of the Fraternity for Children, Solidarity and Humanism, an Angolan nongovernmental organization locally known as FISH, want to hear. The group has been staging such events throughout this capital since December, targeting women, young people and prostitutes.

With the recent end to Angola’s 27-year civil war, activist groups say the time is right to launch a full-court press to stop AIDS from devastating this southwestern African nation.

“In this moment of peace, we are all united, so let’s fight this terrible illness,” said Alice Neto, a community activist with FISH.

The war gave Angola all the right ingredients for the epidemic to thrive. Four million people were driven from their homes, straight into a migratory life racked by poverty. High unemployment led many women to sell their bodies. Unruly soldiers and police officers used their weapons and social influence to command free and typically unprotected sex, AIDS activists here say.

Now, the cessation of fighting has opened up access to once-besieged towns and provinces. The fear is that the free flow of people will enable HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, to circulate even more rapidly.

“The war helped the spread of AIDS, because there were many people, like the UNITA [rebel] soldiers and their families, who didn’t have access to information,” said Osvaldo Colsoul Reinaldo Melin, president of Humanitarian Action United Angola, a local group that runs a project called Stop AIDS. “With peace, there is a need to work even harder to prevent it.”

Statistics from the Angolan government put the number of people infected with the human immunodeficiency virus at about 8,000 out of a population of 2 million. The United Nations, however, estimates that more than half a million Angolans live with the virus. This figure could be even higher, local activists insist, because of the low rate of reporting cases of HIV infection and Angola’s limited capacity to test for the virus.

And although Angola’s infection rate appears to be lower than that of other southern African nations, where about 20% of adults are HIV-positive, activists here believe that this country’s rate could easily spiral.

More than 82,000 former guerrillas and 250,000 of their family members have moved into demobilization camps since the end of the war in April. UNICEF reportedly plans to inundate the camps with condoms and information about AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases, and train military health personnel.

Strapped for cash, many local nongovernmental organizations have been forced to sell condoms rather than give them away, providing a convenient excuse to many people not to use them.

Ignorance about the disease and ways to prevent it is widespread, said Antonio Montiero, a coordinator with Population Services International, a U.S.-funded group that helps local groups with AIDS prevention initiatives.

Montiero explained that common myths about the disease include the belief that AIDS is a “white man’s disease” invented by Europeans to try to exterminate Africans; that only prostitutes and promiscuous people can get AIDS; and that condoms make men sterile.

In a survey conducted in Luanda last year by Montiero’s group in coordination with the World Health Organization, 70% said they didn’t believe that condoms were effective in preventing the spread of HIV; 34% said the contraceptive reduced sexual pleasure.

Such perceptions have left AIDS awareness groups scrambling to come up with creative ways to grab attention.

Officials of the Stop AIDS project fan out across the city, distributing anti-AIDS pamphlets and booklets to taxi drivers, truckers and passersby. The literature includes photos of some of the ghastly effects of sexually transmitted diseases.

“Sometimes the pictures shock people,” said Melin of the Stop AIDS project. “But when they see these pictures, they become aware faster and they start believing faster.”

FISH officials use similar scare tactics in graphic films they show about how to use condoms properly and the impact of living with the virus.

Many AIDS activists believe that the message is gradually sinking in, with anecdotal evidence indicating that many people are becoming more comfortable with talking about the virus.

“I think the film is good,” said Feliciana Armando, 27, a sex worker since 1992. “It has helped me protect myself by showing me how important it is to use condom so that I don’t get infected.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.