Dam Scam Sent L.A. County Supervisor Up the River

Crooked politicians in Depression-era Los Angeles found “easy pickins” when they meshed their hunger for money with the arid state’s thirst for water.

In what became known as the Great Forks Dam fiasco, and what county Supervisor John Anson Ford called “the darkest episode” in the history of Los Angeles County government, a county supervisor--evidently the only one in modern times to go to prison for corruption--was handed an envelope full of $1,000 bills on a street corner the day after he persuaded his board colleagues to vote for a huge cash payout to the contractor who paid him the bribe.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. June 29, 2002 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Saturday June 29, 2002 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 9 inches; 348 words Type of Material: Correction

Dam scam--The “Then and Now’’ feature in Sunday’s California section said Southern California woke on the morning of March 12, 1928, to the St. Francis Dam disaster. The dam broke early on the morning of March 13.

For most of the early decades of the 20th century, the city of Los Angeles was nationally notorious for its corrupt mayors, bagman cops and dishonest politicians. But the county government had escaped this bad PR--until 1933, when Supervisor Sidney T. Graves was clapped into handcuffs, hauled into court and sent to San Quentin for bribery.

Graves was a state assemblyman when he decided to run for county supervisor in the late 1920s. Then as now there were only five supervisors, and Graves won the 3rd District seat.

Along with his supervisor’s title and perks came committee work--including the job as head of the rich and influential county flood control district.

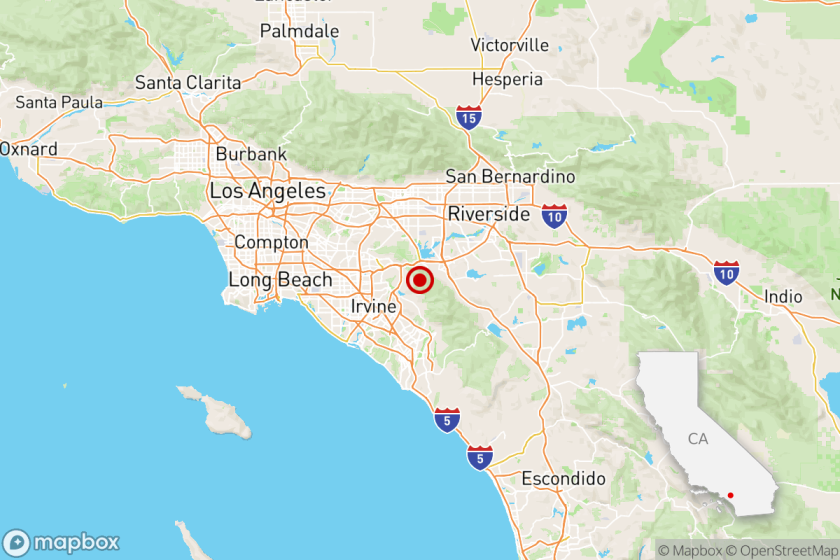

Before Graves took office, voters had approved $25 million in bonds to build a dam above Azusa and to lay $300,000 in railroad tracks to reach the 12 miles from the Santa Fe Railway line to the dam site. Boosters said the dam would be the world’s largest concrete structure, creating a reservoir with a water surface of eight square miles.

It was called the Forks Dam project, and somewhere along the line Graves saw an opportunity for himself. Once the board gave the dam building contract to a San Francisco construction firm and signed off, Graves, as the man in charge of county flood control, was also in charge of how the money was spent.

Almost from the beginning, the contractors used shoddy materials, grossly overbilled the county and covered up engineering faults--and Graves, according to the paper trail, began approving all that, knowing it was substandard.

Southern California was appalled to wake on the morning of March 13, 1928, and learn that the huge St. Francis Dam, north of Saugus, had burst the night before, sending 12 billion gallons of water down San Francisquito Canyon and killing 450 people. The disaster was originally attributed to engineering errors, but later to an undetected underground landslide.

Out at the Forks Dam site, groundwork continued, and the first shovelful of dirt was turned about a year after the St. Francis Dam disaster. Although dam safety concerns were working their way through the state Legislature, no laws would be passed until after the Forks Dam construction was underway.

County Chief Engineer E.C. Eaton reassured Graves and the other supervisors that the Forks Dam site was safe, and so more than 600 workers, along with equipment and construction material, were taken by rail to the site.

On Sept. 16, 1929, up in Azusa Canyon, the earth roared, lurched and shifted as tons of dirt and rock that had been excavated suddenly shifted. Water and power lines and the new rail lines were destroyed. The new west wall of the dam was crushed.

No one was injured in the landslide, because no one was working in that area. The day before, Eaton had noticed earth movement there, and had ordered the workers out. No one wanted another St. Francis disaster.

State engineers almost immediately revoked the county’s permit to build Forks Dam. Even though it was the state that had ordered the project stopped, the contractors turned around and sued the county for big money.

Among other things, the contractors wanted to be reimbursed for their equipment ruined in the landslide. But the problem was, the equipment--with the blessing of Graves--had been appraised on paper at much more than its actual value.

In January 1930, the Board of Supervisors, urged on by Graves, agreed to settle the suit and pay $830,000 to the contracting firm--about eight times the worth of the lost equipment. And it wasn’t long before rumors of bribery and corruption began surfacing.

The rumors reached the county’s grand jury, which launched what became a three-year closed-door probe by three special teams of investigators.

One team, curiously, was a private group called the Pomona Taxpayers Protective Assn., which was enlisted by the grand jury to sniff around the Azusa disaster. They joined forces with the grand jury’s own investigators and with a county-appointed team called the “Minute Men”: two attorneys, a geologist, a former U.S. Army engineer and a businessman.

Working together, the three groups ultimately uncovered an $80,000 cash “transfer” from the contracting company to Graves. On the day after the Board of Supervisors voted to pay off the contractors to the aforementioned tune of $830,000, Graves went to San Francisco, where, on a street corner, he was handed his reward for getting the vote: an envelope stuffed with 80 $1,000 bills.

The three teams also found evidence of an attempted land swindle orchestrated by Supervisor Hugh A. Thatcher. A friend of Thatcher’s, a wealthy orange-grower named Murray Vosburg, owned 800 acres in Azusa below the dam site. It wasn’t worth much until Thatcher tried to persuade his fellow board members to buy the land as a “spreading ground” for flood control--at eight times its real value. Thatcher was never taken to trial, but lost his bid for reelection.

Graves went into court in 1933 with all his flags flying. He hired celebrated attorney Jerry Giesler, who knew all about being a defense attorney and said of his job: “My clients don’t want justice: They want off.”

Graves’ good buddy, tongue-tied fellow supervisor and future Los Angeles mayor Frank Shaw, helped his pal Graves by refusing to admit anything on the stand. (There was speculation that Shaw had been on the receiving end of some of those $1,000 bills.) Shaw was elected L.A.’s mayor not long after Graves went to San Quentin, and four years after that, he became the first American mayor to be recalled.

In spite of Giesler, prosecutor Eugene Williams’ case swayed the jury, and Graves was convicted of bribery for influencing the vote.

Although the San Francisco contracting firm was also indicted for allegedly offering the bribe, it was never brought to trial, for which Dist. Atty. Buron Fitts was severely scourged by the city’s newspapers for “failure to perform his public duty.”

The L.A. County Board of Supervisors and Chief Engineer Eaton got off with press scoldings for the gross engineering mistakes and mismanagement of funds.

Undeterred through all of this, the flood control agency found another site to build a dam in the forest above Azusa. In 1935, the new dam was christened the Prescott F. Cogswell Dam, in honor of the county supervisor who was celebrated as the “father of flood control.” It was the first in a series of reservoirs that capture 210 square miles of mountain watershed.

Graves was released from San Quentin in 1937, after serving three years of a six-year sentence, and he had barely changed back into civilian clothes when the federal government came down on him for tax evasion: failing to report the $80,000 bribe as income.

He was convicted and sentenced to serve two years in federal prison at Terminal Island. Graves died in 1958, at age 76.

--- UNPUBLISHED NOTE --- This story has been edited to clarify a portion of the original published text. While flooding occurred early on the morning of March 13, 1928 the dam actually broke at 11:57 p.m. on March 12. --- END NOTE ---

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.