Brother, What a Switch

Before shooting “The Grey Zone,” the film version of his own dark Holocaust play, director Tim Blake Nelson handed out a required reading list to actors David Arquette, Harvey Keitel, Steve Buscemi and Mira Sorvino, among others.

First, there was Primo Levi’s essay of the same name about the Sonderkommando--Auschwitz-Birkenau prisoners forced to choose between helping the Nazis or death. There were diaries unearthed at Birkenau, packets of testimony from concentration camp survivors, and a 25-page, single-spaced memo from Nelson detailing the authentic, unsentimental tone he hoped to achieve with his story about an ill-fated 1944 uprising of the Sonderkommando.

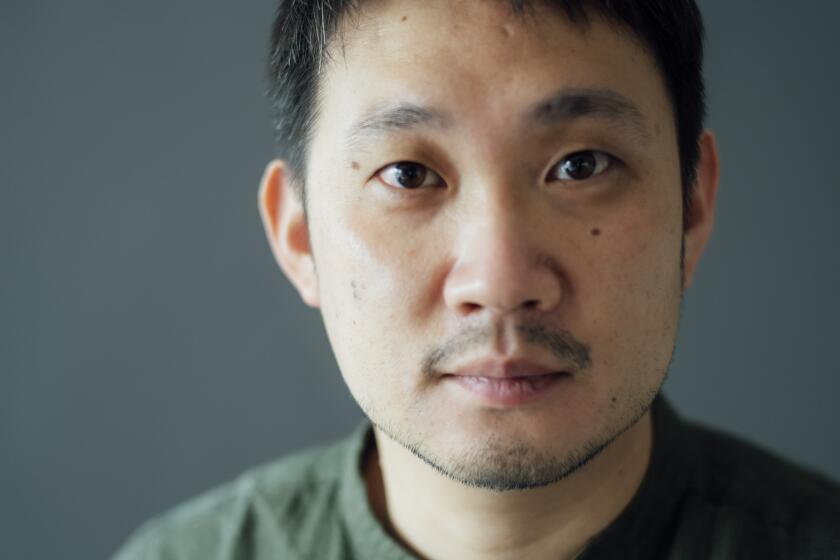

This, then, is the other Tim Blake Nelson. Not the hilarious, gap-toothed actor-singer known for his convincing portrayals of Delmar, the dim-bulb hillbilly in “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” and Bubba, the frustratingly likable pot-smoking schemer in “The Good Girl,” but the serious, erudite and self-aware Nelson, the precariously eclectic writer-director of “Eye of God,” a Sundance favorite about faith and love; “O,” the preppy adaptation of Othello; and now “The Grey Zone,” opening Oct. 11, a labor of love even its backers knew would be commercially hopeless.

Having shed his Hollywood outsider status, Nelson is now poised on the edge of what he calls an insider trap. “I know I don’t want to be involved in cookie-cutter movies,” he said. So far, he said, he’s been lucky as an actor that interesting movies have chosen him. As a director, he said, “I want to direct films that I can’t live without shooting. It’s that simple.”

Like a number of other Hollywood insider-outsiders such as actor-turned-writer Mike White (“Chuck & Buck”), or actor-directors Tim Roth (“The War Zone”) and Tim Robbins (“Dead Man Walking”), Nelson seems drawn to darker, edgier material in his own films while he works as an actor on more mainstream material.

Poolside at the low-key Avalon Hotel in Beverly Hills, the modishly stubbled Nelson sipped espresso for breakfast. He kissed his pregnant wife, actress Lisa Benavides, goodbye and shielded himself from the morning sun. At 38, he’s a slight 5 feet 6, an intense yet unneurotic New Yorker born and raised in Tulsa, Okla., and educated in the classics and drama at Brown University and Juilliard Theater Center. His voice projects education, sincerity and sly wit.

It’s funny, he said, how people compliment him these days on his taste in movie projects. “I think I do have taste, but my career is no manifestation of that. It’s a manifestation of a lot of fortunate rejections which were heartbreaking at the time. For most of the 1990s, before Joel Coen called and asked me to do ‘O Brother, Where Art Thou?,’ I was begging to be in any movie that would have me. I can’t tell you the level of disappointment I experienced when I was not offered the role of one of the Ferengi in “Star Trek: Voyager.’ ”

He realized as a student that he would have to branch out from acting to get work. “Quite frankly, if you look like me,” he said, “it’s downright essential.” Nelson said teachers told him, “You’re short. You’re odd-looking. And it’s just going to be difficult.” Not wanting to sit around waiting for the phone to ring, Nelson started writing and directing plays for his classmates.

Nelson’s friends know him as a book-smart and street-smart intellectual who is prone to using Latin-based words that sometimes baffle them. So it’s ironic that his most enduring characters have been inarticulate simpletons and nerds.

Explaining how an intellectual plays a nitwit, Nelson said it’s an actor’s job to take seriously the outrageous or funny predicaments in which his character finds himself. He said he decided to make Delmar “innocent of knowledge. To me, that felt like a positive choice. When knowledge did come to him, it was a wonderful or a dangerous or a saddening surprise. All that’s positive. It allows you never to condescend to the character, which is the pitfall of any role, particularly in a comedy.”

This year, Nelson has appeared in Steven Spielberg’s “Minority Report” and will star in director Andrew Davis’ film adaptation of the popular teen novel “Holes.” To his former teachers’ undoubted shock, he has even landed romantic leads in “A Foreign Affair,” a comedy about two brothers (Nelson and David Arquette) who travel to Russia to find traditional wives, and Finn Taylor’s “Cherish,” a music-filled comedy released earlier this year to mixed reviews about a young woman under house arrest who falls for her nerdy parole officer (Nelson).

Nelson, a product of both the Sundance writers and directors labs in 1996, said that wise and generous mentors have appeared at crucial junctures in his career. He said he’s learned something from every director he’s worked with, from Terrence Malick (Nelson had a small role in “The Thin Red Line”) to Spielberg, Coen and Taylor. Coen offered advice when he ran into trouble shooting and cutting “The Grey Zone,” Nelson said.

As a writer, he said, he works haphazardly. “Eye of God” was based on a single scene toward the end, when a battered wife takes out her prosthetic eye and shows it to a young friend. “The Grey Zone”--a personal project that began with stories he heard about his grandparents’ escape from Germany--was his second attempt to say something new in the Holocaust genre.

No matter if Holocaust films are heroic (“Schindler’s List”), fantastic (“Life Is Beautiful”) or tragic, documented realism (“Shoah”), audiences generally know what to expect: Nazis kill Jews on a mind-boggling scale, some people survive, and their stories offer either redemption or caution. There is often a common emotional strategy used in the stories and even the scores are similar.

In contrast, Nelson said, “there is no musical score in ‘The Grey Zone.’ And it’s not about survivors.” The film relies on its audience being very knowledgeable about the Holocaust. “If you weren’t able to harness your knowledge of it from movies you’ve seen before, you’d be utterly at sea,” he said.

At first, Nelson had planned to write a play about his family’s experiences, but he scrapped that effort. “It was purgative for me but not something worth spending an audience’s time,” he said.

Through his own research, Nelson uncovered little-known stories of the Sonderkommando who, unlike the kapos who kept fellow Jewish prisoners in line in their barracks, helped prepare prisoners for gas chamber deaths and disposed of the bodies. “As a Jew and a human being reading about people faced with a predicament more quintessentially human than any I can think of,” he said.

“The Grey Zone” play was produced off-Broadway in 1996 at the Manhattan Class Company and won numerous awards, including four Obies and New York Newsday’s Oppenheimer Prize.

As a movie, however, the bleak, no-heroes subject made typical Hollywood financing nearly impossible. Eventually, with Harvey Keitel signed on as producer and cast member (he plays a cynical German official in charge of a crematorium), Nelson persuaded Avi and Danny Lerner, Israeli partners of Los Angeles-based Nu Image/Millennium, a film production and distribution company, to provide the $4-million budget. (Eventually the film was sold to Lions Gate, which will release it.) Avi Lerner said he never expected to make a profit on the film. “There’s no commerciality in this kind of movie. We always look at one thing. Can we make a profit or not? This movie, you do it for the memory, for something special for the Jewish nation.”

Growing up in Israel, Lerner said, he often wondered why anyone would help the Nazis. “You ask yourself why, why and why? That’s the reason I made this movie.” The movie was shot in and around Sofia, Bulgaria, where the Lerners have made several B movies. The emotionally taxing film could never have been made in Hollywood, he said. As many as 850 Bulgarians worked as extras, shaving their heads and often appearing naked. “One day, I found myself in our gas chamber with 250 naked Bulgarians covered in movie excrement and blood, ages 5 to 80, male and female, piled on top of each other. I honestly felt I was going mad at that point,” Nelson said.

“We all may have felt that to some extent,” said David Arquette, who plays an unlikely role as a Sonderkommando who beats another Jewish prisoner to death. Known mostly for his silly persona in movies (“Ready to Rumble”) and TV ads for a phone company, Arquette said that Nelson gave him a shot at the film because they had met on a miniseries, “Dead Man’s Walk,” and became friends.

“As an actor, I’ve never met anyone who’s as caring and is so interested and concerned with the actors’ comfort,” he said. “After certain takes, he’d hug me and kiss the top of my head, fatherly in a way. It was really nurturing and vulnerable on his part.”

On the festival circuit for a year, “The Grey Zone” has drawn some criticism for its stylized, Mamet-like dialogue and praise for its vivid and horrifying authenticity. “It’s a very hard movie to watch,” Lerner said. At a film festival in Israel, many people in the audience could not bear to look at the screen, he said.

Holocaust historians also said the movie could be controversial if the Sonderkommando are portrayed as collaborators. “We must not apologize for that kind of behavior,” said Rabbi Marvin Hier of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in L.A. “They were not heroic figures. But they absolutely were not collaborators. They were victims themselves doomed for extinction.”

Nelson, however, hopes his film will transcend politics. “I believe, perhaps a little presumptuously, that this is more a story about what it is to be human than it is a Holocaust story. As a writer and filmmaker or novelist or painter, you have to find a tiny place to write about. The more specific you are, and the more true you are to that little world, the more universal it’s actually going to seem. It’s that classic paradox.”

*

Lynn Smith is a Times staff writer.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.