In Russia, Defanged B-52 Is Da Bomb

For a few brief moments, a patch of sky darkened Wednesday over this wooded Moscow suburb, and the screeching black profile that Russians spent years learning to hate -- the U.S. B-52 Stratofortress, or, to those from an earlier era, simply the plane that would be delivering the Bomb when it came -- touched down at a Russian military airfield.

Inside the cockpit, where a U.S. Air Force crew had flown more than 13 hours from Minot, N.D., the approach had been dramatic: a countdown of the last few miles before entering Russian airspace, an improbable flight over downtown Moscow and touchdown at an airfield they had seen only on their war-game-simulator flights.

On the tarmac, crowds of Russians maneuvered around the plane that has been the Darth Vader of the American strategic arsenal for 50 years and entreated passersby to photograph them standing in front of it.

Images of the demise of the Cold War have been so numerous they are now unremarkable. Except, perhaps, for this day at the Moscow Air Show, when the B-52 joined U.S. F-15s and F-16s for the first official demonstrations of American military airpower on Russian soil.

Throughout the week, U.S. pilots are offering up to 1 million spectators at Russia’s equivalent of the Paris Air Show demonstrations of their flying machines, alongside similar air spectacles by their Russian counterparts, the Black Knights and the Swifts, and aerial-performance groups from France and Italy.

The fighter jets took a back seat Wednesday to the venerable B-52, which as late as 1968 patrolled the skies of the Earth 24 hours a day, each of the planes laden with 50 megatons of nuclear bombs that on the last day of life as anyone knew it were destined for delivery to Moscow and other Russian targets.

As late as 1991, fleets of B-52s maintained ground-alert postures at U.S. Strategic Air Command bases, loaded and parked at the edges of runways, ready for instant deployment in combat with, as actor Slim Pickens memorably called them in his role as a B-52 commander in the 1964 film “Dr. Strangelove” -- “the Russkies.”

Now, here was the flat-black profile of the 1961-vintage bomber -- since used heavily with conventional weapons in Vietnam, Kuwait, Afghanistan and Iraq -- sitting on a Russian runway, only a few hundred feet from the workhorse of the Russian bombing fleet, the Tu-95 Bear, and its more modern counterpart, the Tu-160.

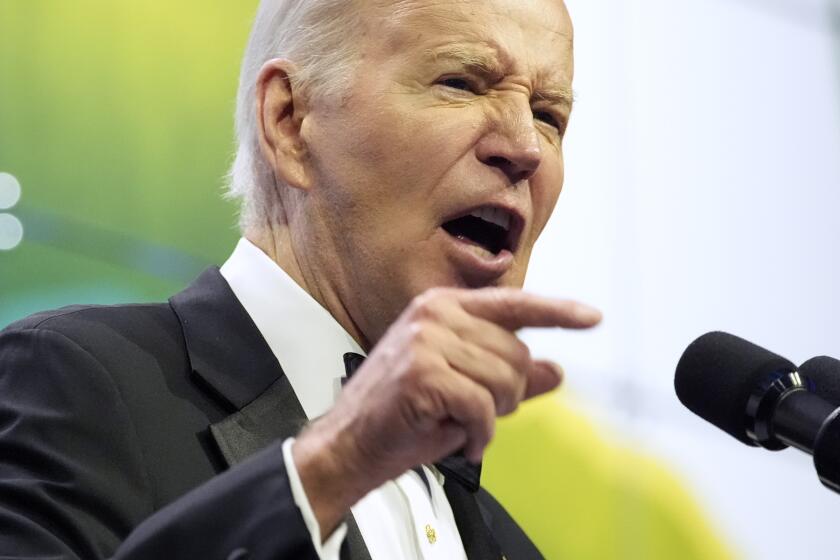

“It has extreme symbolic significance for us, after all the years of Cold War confrontation. This is the plane they scared us with for all those decades,” said Magomed Tolboyev, a former cosmonaut and test pilot who is president of the air show.

“This was the plane that could have brought nuclear weapons to Russia, and now it’s quietly sitting here like in a zoo. An alligator with no teeth,” he said.

The eight-member U.S. air crew was jubilant. “To be told, ‘You have permission to enter Russian airspace’ -- I never thought I’d hear that in my lifetime,” said Lt. Col. Rob Bussian, the B-52 squadron commander from Minot Air Force Base who piloted the plane. “And then, to fly over downtown Moscow?”

Lt. Col. Bill Panande, radar navigator on the flight, said the crew flew over Canada, refueled over the North Sea, then crossed the Baltic Sea and Latvia. “After that, we were counting it down out loud: 10 miles to go. Five miles. Three miles. OK, guys, we’re in Russia,” Panande related.

Shortly after touchdown, after the pilots had filled out Russian customs forms, Tolboyev climbed into the pilot’s seat and got a rundown on the controls from Bussian.

“CRTs, flap handle displays, new avionics,” the American pilot said, fingering each. “Also, low-light TV, and we used this for the first time in Iraq, a laser-targeting pod.”

Tolboyev nodded knowingly. “Aerial refueling?” he said.

“Yes, the doors are up here.”

“I used to refuel fighters, and I never understood at the time how it was possible to refuel such an aircraft,” Tolboyev said. “But I feel like I’m sitting in a normal Russian aircraft. No difference at all.”

The end of the Cold War and the collapse of communism have hit the Russian air force particularly hard, with shrinking budgets taking their toll on both equipment and training.

This month, three military aircraft crashed in unrelated accidents on a single day, and even as the air show got underway, searchers were combing the Kamchatka Peninsula for an Mi-8 helicopter that disappeared Wednesday, carrying a regional governor and 16 other people.

Russian air force chief Vladimir Mikhailov, after the crashes, lamented inadequate air crew skills, saying military pilots now fly an average of 40 hours a year, less than the required minimum of 100 hours. U.S. pilots, by contrast, normally log hundreds of hours each year.

“The current military-technical revolution, which is in full bloom in the West, is bypassing Russia,” said Pavel Felgengauer, an independent military analyst in Moscow. “Russia seems to be incapable of producing new high-tech weapons and hardware anymore. Even at this air show, what they can demonstrate was either produced or designed in Soviet times.”

Still, next year the Russian air force is scheduled, after several years of money-induced delays, to start receiving a modernized version of the MIG-29 fighter and an upgraded variant of the MIG-31, along with a new long-range air defense missile, the S-400.

And when it comes to planes, for many of the aviation professionals gathered this week at Russia’s premier aircraft testing facility -- whose 3.4-mile runway is the longest in Europe -- there is an abiding affection for the tried and true.

As crowds gathered around the B-52, Maj. Andrei Schegolikhin pointed at the gleaming frame nearby of the Tu-95, the big turboprop missile carrier that has been the mainstay of the Soviet strategic bombing force.

“That was your enemy during the Cold War,” he said, nodding his head.

“During the times of the Cold War, they [the Tu-95 and the B-52] patrolled the skies together along the border lines and the neutral zones, in the Far East for example.

“They even knew the faces of each other,” he said.

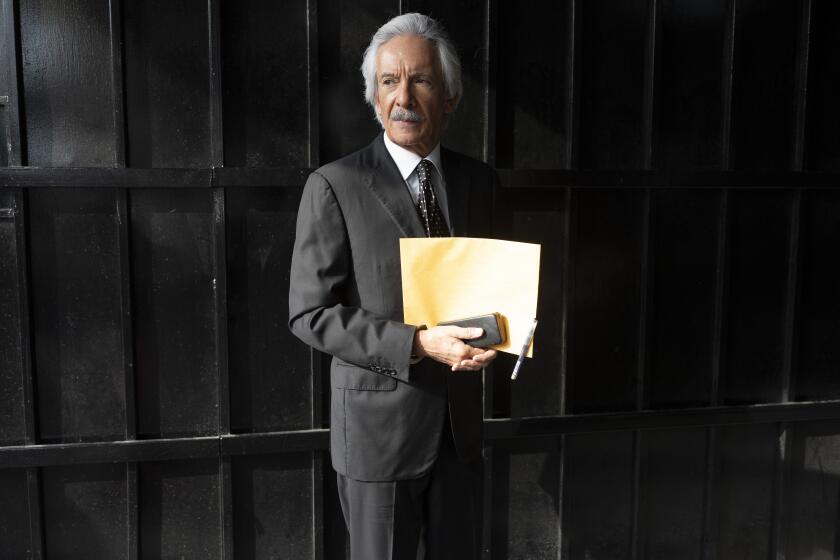

Then he pointed to a man in a dark suit who was standing alone and gazing up at the old bomber: Dmitri A. Antonov, chief designer on the Tu-95 for Tupolev Aircraft since the 1980s. “Talk to him,” Schegolikhin advised.

Antonov appeared reticent to speak at first but warmed to a question about whether the Tu-95 was a better aircraft.

“This plane has more or less the same speed as the B-52, and I would like to point out that the B-52 has eight engines, and this plane has only four. We proved that you could reach maximum speed with these type of engines,” he said.

He went on talking about swept-back wing designs, turboprops versus jet engines, how long each plane could fly between refuelings.

“It is hard to compare two planes, but for me, this machine is the best,” he said, looking at his plane. “It’s a beauty. I am in love with it.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.