A Delicate Duet of Policing

By all appearances, Col. Raad Abbas Jasim seems like a typical police chief. The white star and eagle on his uniform denote his seniority. Officers rush into his office to get his signature on warrants. When citizens have a beef, it’s his desk they pound.

But just behind Jasim at the Khudra district police station these days is a constant shadow: a 23-year-old female lieutenant with the U.S. Army’s 18th Military Police Brigade. Like a supervisor monitoring a new hire, Rachel Amilcar hovers at Jasim’s back, listens in on his meetings and occasionally overrules him.

“We try to reach agreement, but if we disagree, we must go with her decision,” Jasim, 42, says, sounding less than entirely satisfied with the situation.

When a reporter questions him about progress in the investigation of the Jordanian Embassy bombing in the capital this month, he begins to speak, then cuts himself off and turns to Amilcar, sitting silently next to his desk.

“Am I allowed?” he asks through an interpreter. “This is your decision,” she responds.

It’s an awkward moment that speaks volumes about the challenge the United States faces in attempting to hand over police work to the Iraqis. U.S. officials are eager to reduce the military’s responsibility and put Iraqis back in charge of their own country. But the Americans say they aren’t willing to turn over the reins just yet, not until they show the Iraqis how to do things their way.

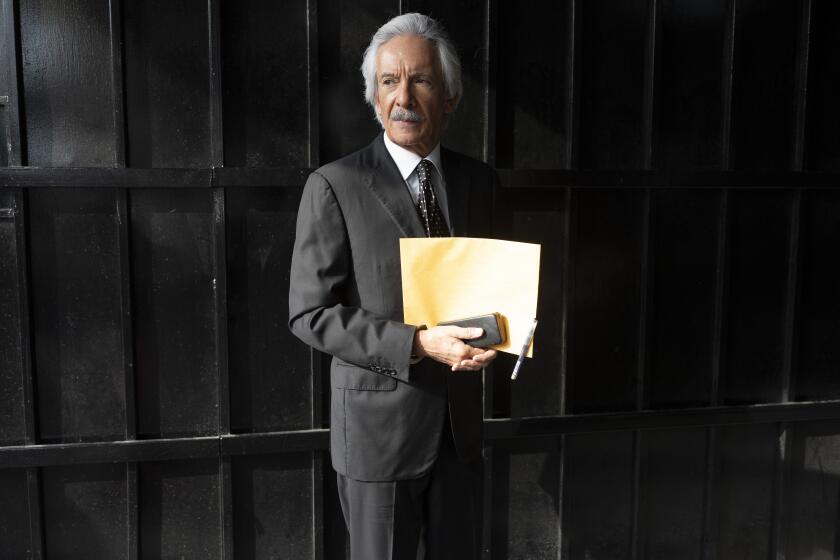

“As we start to feel more comfortable with Iraqis, then we will start to transition away,” said Bernard Kerik, the former New York City police commissioner who is overseeing the effort to rebuild Iraq’s force.

At the Khudra station, it’s clear that the process is off to a tenuous start.

Iraqi police say they appreciate some of the new equipment and training Americans are providing, but they resent being lectured by U.S. soldiers half their age. They ridicule Americans as too soft on the bad guys and have shown more than once that they know best how to catch criminals of the sort they’ve been chasing for years. Iraqis also worry that the United States is trying to impose a Western-style justice system that doesn’t always translate in their Muslim-dominated culture.

“We have the same aim: to prevent crime. Be we don’t understand some of their ways, and they don’t understand ours,” said Jasim, a 19-year police veteran. “Somehow, we managed to do it before the Americans were here.”

Americans counter that the old Iraqi police system -- often used as an instrument of oppression during Saddam Hussein’s regime -- was undisciplined and plagued by corruption. Suspects were routinely beaten, U.S. officials say, and cops solicited bribes from citizens to compensate for the low police salaries.

According to Kerik, Iraqis need to learn some basics. “It seems normal to us, but you have to explain to them that you can’t do things like torture and physical abuse,” he said.

Kerik has fired about 7,000 former Iraqi officers, many of them Baath Party members, for alleged offenses as serious as rape and murder. Frustrated that traffic cops often leave their posts during the blistering afternoon hours, he’s threatened to sack anyone not found at his assigned intersection.

With a current nationwide force of 35,000 -- about 5,000 of them in Baghdad -- Kerik is putting hundreds of top officers through a three-week crash course in human rights and policing in a free society. Coalition authorities also plan to send Iraqi cops to training facilities overseas -- one destination is Hungary -- due to a lack of capacity at academies in Iraq.

But the force is still only 50% of full strength and there are critical shortages of patrol cars, uniforms and firepower at a time when violent crime and terrorism are soaring. Kerik has set up an ambitious program to recruit and train another 35,000 officers in 18 months.

“The bottom line is this is going to work,” said Kerik, who plans to return to New York in September after nearly four months in Iraq. “The mind-set will change.”

Kerik’s replacement hasn’t been named, but he appears to be grooming Ahmed Ibrahim, recently promoted to senior deputy of the Interior Ministry, to take charge of the police once he’s gone.

So far, however, U.S. officials appear hesitant to cede too much control.

In the immediate aftermath of the Jordanian Embassy attack, U.S. officials attempted to let Iraqi police take the lead in the investigation. But by the second day it was clear the force was ill equipped to handle such a massive probe, and the FBI took charge, relegating the Iraqis to assisting U.S. troops in guarding the crime scene.

After last week’s U.N. bombing, officials announced a “joint investigation” with Iraqi police and the FBI. But recent interviews with Iraqi police chiefs revealed that U.S. officials had not even allowed them to handle the bodies of victims, much less shared details about the search for the culprits.

At the recently refurbished Khudra station, it’s mostly small-time and domestic crimes that the police deal with. A woman with a black eye reports that her husband beat her. A man demands to see his stolen car, which he believes the police have recovered. A desperate mother presses to visit her son, who was jailed after accidentally striking a child with his car.

Sgt. Alan George, a 27-year-old American, shadows Iraqi 1st Lt. Alla Adnan at the public counter. The secret to making their partnership succeed, he says, is a light touch.

“I try to let him do his job,” George says. “You have to be respectful. This guy is probably 20 years my senior.”

“George is good,” Adnan says in English, patting the U.S. soldier on the back.

When a carjacking report comes in, George watches Adnan collect the relevant information. Then Adnan settles back into his chair.

“How about using the radio to call that out to your patrols?” George suggests. Adnan follows the advice.

Other soldiers at the station have a shorter fuse. “I’m sick of you guys not doing what I tell you to do!” Sgt. Shawn Hoaglund barks at a group of Iraqi officers.

The dynamic between Jasim and Amilcar is perhaps the most complicated. “Her experience in crime is not as wide as mine,” he notes. Asked if he finds it difficult in a male-dominated society to take orders from an American woman young enough to be his daughter, Jasim responds, “A successful police officer is able to manage all things.” Amilcar declined to be interviewed.

Kerik appears to relish the U.S.-imposed gender role reversal. Speaking about another female soldier he has supervising an Iraqi police chief, he says: “It’s great. She’s all over those guys and in their face. But they love it.”

Kerik has vowed to hire and train the first female Iraqi police officers, but Jasim is confident there will be no women at his station after the Americans leave, except perhaps those assisting with administrative work. “Our society will not accept this,” he says.

Regular neighborhood patrols are a novel concept to the Iraqi police, who previously stayed in their stations and waited for people to report crimes in person.

Also new are the Motorola wireless radios, the security wall being built around the building and the 5-foot-tall public counter, designed to allow officers to tower over visitors.

But Iraqis seems to have little use for other concepts introduced by the Americans, such as the giant “crime tracking board” behind the desk, which only the Americans seem to use to follow daily incidents.

Some clashes have occurred over treatment of suspects. During a recent interrogation, a handcuffed robbery suspect threatened to retaliate against his interrogator, 2nd Lt. Jameel Ghlaim. “So I hit him in the face,” Ghlaim says. “A threat like that is a crime.”

George intervened. “You can’t do that,” he recalls telling the officer. “What if he turns out to be innocent? Once a suspect stops fighting, it’s hands off.”

Ghlaim laughs off such concerns. “We know best how to make professional criminals confess.”

Sometimes the Iraqis do know best. After a carjacking victim reported receiving a ransom note for her vehicle, Iraqi police decided to organize a sting by hiding in her house and catching the thief when he came to collect the money.

Americans thought no criminal would fall for such a simple trap. But the Iraqis not only caught the culprit, he also provided details about a carjacking ring. “The criminals here aren’t that smart yet,” says Army Spc. Richard Anger.

Because Hussein relied heavily on his own secret police and militia groups, ordinary Iraqi cops rarely garnered much respect -- or cash, earning the equivalent of just $10 to $40 a month. After the war, police stations were badly looted. Even today, when patrol cars turn on their flashing lights, few drivers yield.

But the force may be gradually gaining the respect of citizens, who are reporting crimes and seeking help more frequently.

Now Iraqi officers are grappling with an image problem: being perceived as too closely allied with the Americans. Earlier this summer, someone threw a grenade at the Khudra station, but no one was harmed.

“They call me the dog of America,” Adnan says. “It’s frustrating. Sometimes I feel like resigning.”

The U.S. military is providing added security at the stations, and officers’ pay has been boosted to $150 to $180 a month. Still, they are short of supplies and manpower. The Khudra station, responsible for keeping tabs on an 18-square-mile area, has only three beat-up Datsun pickup trucks for patrols.

Firepower is another issue. On patrol in a popular shopping district, Ghlaim pulls a 7-millimeter pistol from his belt and examines it. It looks like a toy.

“What am I supposed to do with this?” he asks. “Criminals have AK-47s.” Ghlaim’s partner, Capt. Firas Mohammed, brings his own 9-millimeter from home.

Only half the police at Khudra have uniforms, a problem that may have contributed to this month’s accidental shooting of two Iraqi officers by U.S. troops at a nearby station. The soldiers apparently mistook the officers, who were pursuing suspected gang members, for armed criminals. One of the officers was not wearing a uniform.

The U.S. says it is investigating. Meanwhile, Kerik says 50,000 new uniforms and a like number of 9-millimeter pistols are on order and should arrive soon.

The officers also voiced a gripe many U.S. police share: The system lets too many crooks get away.

Under current rules, Jasim and his men have three days to gather the evidence to build a case, whether it’s shoplifting or homicide. When that period ends, suspects are removed from the station’s detention cell and sent to a makeshift prison at the Baghdad airport.

There, U.S.-appointed prosecutors and judges examine the evidence. But frequently, there are gaps and the suspects are released, officers said.

“Why do the Americans want to set criminals free?” asked Ghlaim. “How can we put a case together in just three days?”

Kerik called the approach a temporary solution, promising that Iraqis will create their own justice system once a new constitution is written and courts are fully restored.

As Ghlaim and Mohammed drive along a crowded street, a boy on a bicycle rushes up to their truck and reports seeing two men with an automatic rifle lurking nearby. The officers spin the truck around and apprehend the suspects, proudly bringing their catch back to the station for booking.

But after a couple of minutes, George emerges from the station and shakes his head. “These guys have a permit for a gun,” he says. “They never should have been brought in. They’re going to walk right out of here.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.