Salonen grows into his Sibelius

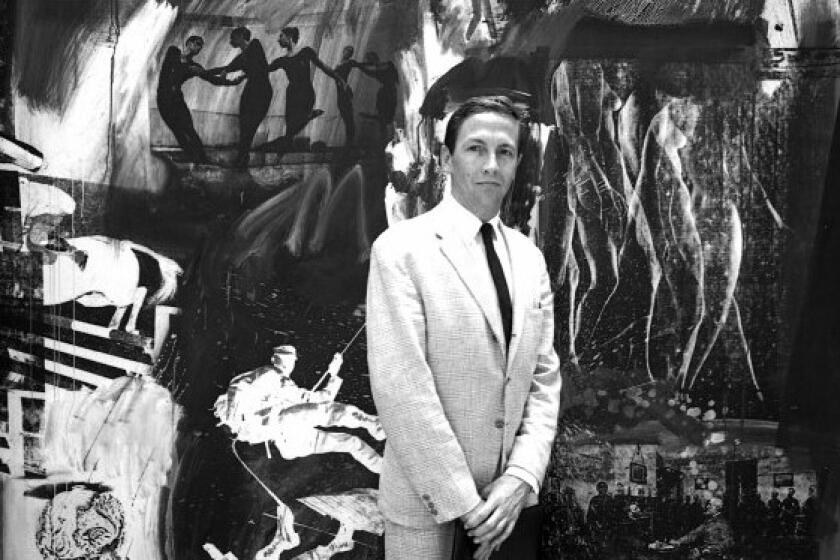

In 1986, Esa-Pekka Salonen, 27 years old and already making a name for himself, recorded Sibelius’ Fifth Symphony with the Philharmonia Orchestra in London. On the CD cover, he is dressed in white tie and tails, with an overcoat draped over his shoulder. The photo is shot from below, making him look towering, a pose almost as pretentious as those Leonard Bernstein took with a cape.

That performance is slow, monumental, self-possessed, and it seemed impressive at the time, if more grandiose than grand. Finnish musicians are typically forced to wear Sibelius, the composer who put their small country on the culture map, as a mantle, and Salonen appeared to be both acknowledging that and asserting his own strength. But he was still very young for a conductor, not yet entirely comfortable with either Sibelius or Salonen.

Now he is. Friday night, he conducted the Los Angeles Philharmonic in a magnificent and revelatory performance of the Sibelius Fifth in Walt Disney Concert Hall. And the revelations were as much about him as they were about Sibelius’ inspirational and original symphony.

The symphony, which usually lasts about half an hour -- although Salonen is still on the slow side and adds a couple of minutes to its length -- is an epic of becoming: a lifting of mists, a representation of a process in which the vague becomes certain, a brooding brightening of moods. Sibelius wrote it in 1914 as a war symphony, but he wasn’t finished with his revisions until 1919.

From the initial rumbling timpani and rising horn figure, a listener can sense that triumph is possible, but as the first movement speeds up, the rush is to something uncertain. Triumph, in fact, is withheld until the symphony’s end, when the horns, emphasizing exhilaration, finally withstand constant harmonic negativity. They blaze to glory, but six sharp chords at the end stop them short. War is never really over, Sibelius seems to remind us.

At Friday’s performance, Salonen brilliantly captured the complex and contradictory Sibelian sensation of a process that feels unstoppable but whose outcome is not inevitable. The parallel between the composer’s reaction to World War I and its aftermath and our own uncertainty about the world situation today was one revelation of this stirring performance.

But the performance also underscored another parallel: that between mature Sibelius and mature Salonen, the composer of such works as “LA Variations.” Although its details were as firmly etched as I have ever heard them, Salonen’s interpretation of the Fifth unfolded the way a flower blooms; you suspect its whole all the while, but you are also completely surprised every step of the way. I’ve encountered only one other conductor who could do that as well in Sibelius, and he was also a composer -- the guy with the cape who also liked to be photographed from below, Bernstein.

Originally, the Philharmonic program was to include a new work by another Finnish master, Magnus Lindberg -- one of the orchestra’s commissions for its first season in Disney -- along with Gidon Kremer playing Bartok’s First Violin Concerto. Lindberg didn’t finish his piece in time (it’s now scheduled for the 2005-06 season), and it was replaced by a recent work by a Swedish composer, Anders Hillborg’s “Exquisite Corpse.” Kremer’s concerto was also changed, to the Sibelius Violin Concerto.

With Kremer as the soulful soloist, we got more great Sibelius, but the concerto is so common these days that I was sorry it was not the seldom-performed early Bartok work or, better yet, the new Michael Nyman Violin Concerto, which Kremer premiered last month with the Boston Symphony.

Hillborg’s “Exquisite Corpse,” written in 2002, is named after the French Surrealists’ dinner game of collectively writing poetry or drawing pictures without any participant’s seeing what the others have done. In this case, the composer strung together things from his own music along with bits of Stravinsky and Sibelius to see what would happen.

What happens is almost Sibelian, another growth process, in this case from a single swelling flute note to a big, percussion-happy climax. Hillborg’s use of the orchestra is rich and deep, and the game he plays proves more affecting than one might have expected. It helped greatly to have a conductor who also knows a thing or two about how to create a sense of flow.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.