West Bank, bearing witness

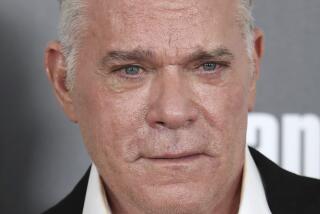

‘Paradise Now,’ a nominee for best foreign-language film, tracks the lives of two Palestinian men as they prepare to become suicide bombers. To play one of the pair, Kais Nashef, a Palestinian who lives in Tel Aviv, spent three months of 2004 in the West Bank city of Nablus. Nashef was immediately drawn into the life of the city, and he offers this account of working in the film’s bleak, turbulent setting.

SITUATION 1

Cab ride on the day of arrival, from the checkpoint to the hotel.

IT is a bright winter day. Sun flashes from a variety of odd corners. Everything seems normal. But still I have the strange sensation of having arrived in another country after a long flight, perhaps because I have just passed the one-way border crossing, or perhaps because I know that I am going to be here for three months. Or perhaps it’s because of something else entirely; something to do with the place itself and the way in which the winter light resting on it is slightly different from the Israeli winter light. I hadn’t felt this way the last time I was in Nablus in ‘87, a few months before the first intifada. Then, I had felt as if I were really only a half-hour’s drive from home.

I speak to the cab driver, who tells of his brother in Qatar, his brother in Kuwait and of his own Saudi background. I get out with all my bags, look around and feel that I am within a pattern of logic I can’t decipher.

Facts:

The city is encircled by a ring of mountains -- checkpoints -- and observation posts that blink red at night on the mountain tops.

The mountains themselves have the proud stance of a military

order.

The day after my arrival, Sheikh Ahmed Ismail Yassin, co-founder of the Palestinian group Hamas, is killed.

Tahi, a sad, smiling man who has a small role in the movie and whose house is located in the heart of the casbah, tries to adopt me and battle my reticent nature.

*

SITUATION 2

Driving around in Tahi’s car the night after Sheikh Yassin’s death.

WHEN night falls, Nablus sweeps the people from its streets and replaces them with a still landscape of subdued lights. It’s 1 a.m. and I’m at the wheel. Tahi tells me to take a right turn toward the Old City. The dark and the state of alert have leached the magic from the arched alleyways. The Israeli Defense Forces are on the alert for acts of revenge for Yassin’s killing, and the Palestinians are on the alert for any preventive strikes by the Israelis.

Tahi directs me into ever-more twisting alleyways. Suddenly he tells me to flash the headlights and honk the horn just once, then turn left. At the end of the alley, about 40 silent men stand holding machine guns, watching our approach. My foot shakes on the clutch more than it did on the day I went for my driver’s license.

Tahi recognizes the men and tries to explain who I am, but they remain silent. “What’s happening, guys?” I ask, but they still don’t say a word. All I see are eyes peering at us from different angles as I try to ignore the Kalashnikovs.

Tahi tells me to drive back, and as I turn the car around, I almost hit one of the men. He comes toward me holding a machine gun the size of a house, shouting, “Why are you driving like that? Why are you driving like that?”

“I’m not a very good driver,” I squeak, and suddenly everyone bursts out laughing. I laugh too.

On the way back to the hotel, Tahi explains that the open spaces of the alleyways are the best hiding places for groups like this; it’s difficult to surprise them there, and there are many possible getaway routes. I realize that in his eyes, these men are heroes protecting the Old City. They seem pretty serious to me, as well, and certainly good material for a Dali painting. The situation brims with the kind of emotion needed for one.

Facts about sound:

The ring of mountains makes it difficult for the sound of mortar shells to escape and it echoes back.

The muffled sound of the old Palestinian guns also returns in a muffled echo.

The noise made by the cries of the masses in protests and funerals also echoes, and it’s difficult to distinguish between what is echo and what is not, making it hard to guess the distance and direction of the din until it seems that it comes from all directions and you think that perhaps it’s soaked into the wind and has nothing to do with something that is really happening.

A thought on the roof:

I stand on the roof of the hotel, learning my lines and looking at the city below, immersed in darkness, swept by chilly winds. It’s amazing how frozen the landscape is; hours go by and you see no movement, as if you’re looking at a picture. And I’m suddenly aware of how anthropological the situation is. They took people, imprisoned them within a few mountains -- let’s see how they begin to behave. From this night on, I see the situation also in terms of a laboratory, test tubes and microscopes.

The average Nablus citizen and a lab mouse could understand each other and find many common topics of conversation.

*

SITUATION 3

Filming in the refugee camp El-Ain.

WE use one of the warehouses as a dressing room. While the German makeup girl slaves away on my face, a woman of about 40 walks in, stands beside us and watches. Her face is tilted, propped by a small, constant smile. In a calm voice she says that she too is in the movie, but she doesn’t know how to act, which is why she’s come to watch the shoot.

She tells me I must play my part convincingly because two of her sons have been killed by the IDF, her husband is in jail and she’s left with only one son at home, a cripple.

Her tone is natural, casual, and someone who doesn’t speak Arabic, such as the German makeup girl, could easily think she is saying something like, “I’m going to buy two packets of sugar and some milk, because I have guests coming over. Maybe I’ll cook for them or better yet bake cookies!”

A while ago I read Hannah Arendt’s book “Eichmann in Jerusalem,” with its famous description of the banality of evil. She claims that when evil has clerks and policemen, offices, marketing and newspapers, it becomes institutionalized and for the most part banal. And now I can see how the sheer scale of killing here has led loss to become as banal as popping out for milk. Since her neighbor’s son had also been killed and his neighbor lost a leg and his neighbor is in jail ... routine.

Facts:

It takes up to 12 hours to reach the nearby town of Jenin.

A lot of people have not left Nablus in several years.

In all the time I spent there, I didn’t see a single happy person.

Everyone has a broken look in their eyes.

Everyone has the memory of

the last time they saw the sea.

*

SITUATION 4

The second month of filming, which did not go as smoothly as the first.

THREE men, their faces hidden with head scarves, break into the production office and demand that we stop filming immediately. They also kidnap our location manager, Hassam Titi, for several hours. Filming stops and marathon discussions begin with various officials of Tanzim, a faction of Al-Fatah. This is a nerve-wracking time of waiting.

Finally, they agree to let us continue filming and disassociate themselves completely from the leader of our masked intruders, a man named Kegan. Now he stands alone in his quest against our movie, perhaps because his hidden agenda is blackmailing the movie production for money. But he still comes back to create a panic in the office. He comes into the hotel entrance trailing trouble, a gun in hand, his chest proud, a hollow soul, shattered morality; a poor guy.

When a Dutch journalist asks me what experiences I will take with me from my stay in Nablus, I tell him I will remember that man, Kegan, as representing all the ignorance and depravity spread across Nablus, the place at which the myth of Palestinian struggle arrived, a struggle I was raised on.

Facts about the tank:

After two weeks I wake up and there, at my window, stands a tank. Children are throwing rocks at it.

The tank moves slowly. Suddenly it gains energy and becomes fast. The children run after it.

The children are happy. Because of the curfew they have no school. The tank’s tracks ruin the roads.

The Palestinians make repairs immediately. And then the tank ruins the roads again, and so forth.

On the news they announce the IDF invasion of Nablus with great pathos. In reality, it lacks all pathos. It’s just three patrolling jeeps and two tanks at two junctions. And happy children.

And maybe the pathos lies with those confined to their homes.

Facts:

The Old City and Balata refugee camp are the flashpoints of confrontation.

In Balata, there are 50 weapons, and in the Old City about 50 as well, and there are fewer people than that who really know how to use them.

The rest are in prison or are no more.

These are the wounds still being licked since Operation Defensive Shield, the IDF’s 2002 military action, the largest in the West Bank since the Six-Day War in 1967.

*

SITUATION 5

A missile hits a car carrying four militants, three of them Tanzim leaders.

THERE are thousands, if not tens of thousands at the funeral. The corpses are held high above the crowd and passed from hand to hand. The bodies are broken, faces left uncovered; I see one that has a mustache. The features of his face have lost their proper order, and under the bedsheet, his body is probably contorted as well, as the fabric flows over him illogically. As it does on the other bodies.

The funeral winds the long way from the northern neighborhoods, through An-Najah National University into the city center and finally to the Balata refugee camp where the bodies are buried.

Many flags and posters of various sizes are brandished. There are constant shouts, surprisingly coordinated. One man, carried on the shoulders of another, keeps yelling out slogans through a megaphone and the others repeat after him. So do I. Deafening bursts of gunfire are let loose in the air, all the time and for no apparent reason.

We pack the alleyways of Balata, which has no sidewalks, only houses and between them an open path. We fill Balata’s main path and the press of the crowd is monumental. Some faint. People peep out from their windows, crying, laughing, calling out or just watching. I look at the walls, bullet-pierced from battle, and something inside me yells out with them, to excess, perhaps to charge myself for the role I’m playing.

Suddenly I am not myself; I help the fainters to rise, I calm the pushers. My yells become battle shouts of challenge, my eyes hold an intensity not my own, my throat a hoarseness I have never known.

I look to my hands and find them carrying the casket of one of the dead. We march toward the cemetery.

The gravestone begins with the word shahid, which means martyr. In the cemetery there is none of the reverence and solemnity usually found in Muslim cemeteries, quite the contrary. There is something spontaneous, almost casual about the atmosphere; if you get tired and want to sit down on one of the gravestones that is fine, and if you want to take a shortcut, stepping on some of the graves with as-yet unfinished tombstones, that is reasonable, because the cemetery in Balata is a part of banal, everyday life and the people of the refugee camp come here very often. This is the town square.

The bodies are buried after a short ceremony. I return to the hotel.

Four facts and an insight:

Most foodstuffs and items of clothing available in all the stores are drab and identical.

The city is packed with cabs. Both local and interurban cabs operate within the city, because it is closed.

The gallery of faces never changes; there is no rotation, as no one leaves and no one comes to visit.

Thinking material reduces accordingly.

Lack of thinking material extinguishes the spark of the eyes.

*

SITUATION 6

Enough. We finish filming in Nablus.

ON our last day we have a farewell party on the roof of the hotel. We have dinner together, speeches are made, we drink beer and the guys from Nablus weep. Everyone weeps, without exception. Even those who keep up a stern demeanor and don’t seem as if they were about to.

The artists cry, the office workers cry, the catering staff cries; Muthana, the director’s assistant, recites a purely sentimental poem he has written and then cries, the drivers cry. Everyone cries copiously except Tahi, who doesn’t cry but smiles more than usual. It takes a very long while for the tearful atmosphere to end.

I don’t cry, I only watch and can’t understand.

Perhaps they cry because filming will continue in Nazareth and then Tel Aviv, while they stay here.

And perhaps they cry because for three months they had left their familiar reality and lived in a dream of filmmaking, and now it is all over.

Facts:

In this country called Nablus there is no theater.

No cinema.

No music.

No satire.

No criticism.

No bohemia.

No love.

No life.

There is religion.

There is life after death.

*

SITUATION 7

Return to Tel Aviv

THE place feels unfamiliar to me now and I can’t believe it truly exists. I feel it subsists in a bubble of illusion that has no foundations. I feel it is the smiling face of festering guts and a cracked heart called Nablus.

I have been in the West Bank and seen the nuances of this festering, and now I walk through Shenkin Street and see a man on roller skates. I see a woman buying ice cream looking happy and enjoying her ice cream, and I know she is only half happy, because she can only define herself around that festering.

For me, at least, the ice cream in Shenkin is less appetizing; it reminds me of the gunfire, the dead, the soldiers and the crippled. I can’t look at Tel Aviv without seeing it as the happy facade hiding the dark, sweaty stories beneath.

*

Contact Kais Nashef at calendar.letters@latimes.com.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.