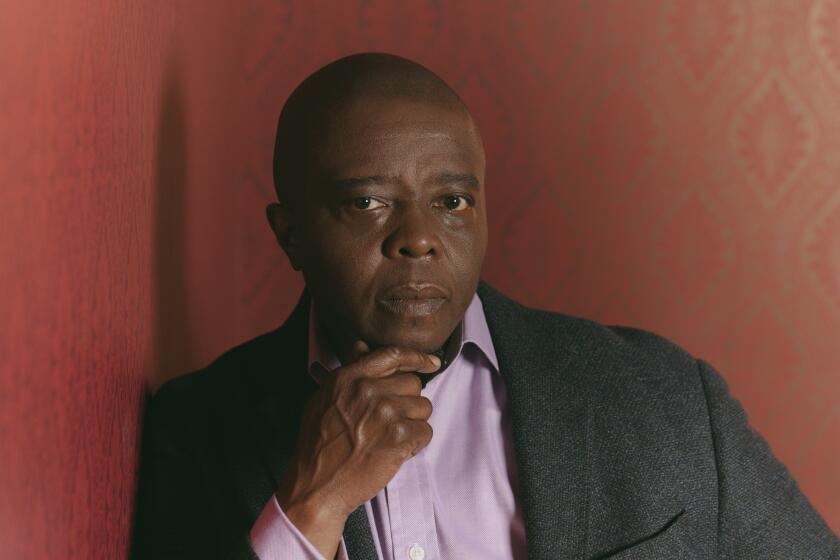

At one with his better half

DOES Eddie Murphy know how good he is as the soulful R&B; singer James “Thunder” Early in “Dreamgirls”? Playing a shimmying satyr on the skids, he seems almost aghast at his prowess. It’s the performance of his career -- a great performance. He has stunned even his most ardent fans, many of whom believed he didn’t have it in him to be a “real” actor, let alone an Oscar nominee.

And yet this is the man who can be seen in the same multiplex playing, among other characters in “Norbit,” a voluminous Gorgon overflowing her garter.

“Eddie Murphy as you love to see him!” run the newspaper ads for “Norbit.” But how exactly do we love to see Eddie Murphy? As big momma? A nebbishy twit, perhaps? How about the megaplump professor Klump or a Beverly Hills cop? As Donkey in “Shrek”? As, God forbid, Dr. Dolittle?

Consistency is not a charge you could ever level at Murphy. But those who see him as a first-time genius in “Dreamgirls” must not have been paying attention. He has often been undervalued as an actor because, for the most part, he has been best in slapstick burlesques such as “Bowfinger” or “The Nutty Professor” (a 1996 performance for which, to its credit, the National Society of Film Critics awarded him best actor). Bottom line: Great actors are not supposed to make fart jokes.

But even if one grants Murphy his glories in these films, his career, despite his pick of the litter, is slathered with simply dreadful stuff. What do we expect of Eddie Murphy? To put the question more directly, what does he expect of himself? He is one of the most commercially successful actors in history and also one of the most confounding.

When Murphy arrived on the scene in 1980 as a member of “Saturday Night Live,” he was, as an African-American, the recipient of two warring traditions: the credit-to-his-race Sidney Poitier syndrome, which was on the downswing, and the so-called blaxploitation cycle, with its Shafts and Super Flys.

Murphy, 19 when he began the show, took a swing at both. He parodied Gumby, Buckwheat, Jesse Jackson, pimps, black power ranters. He was pompadoured James Brown dipping his toe in a hot tub and shrieking “Hot Tub!” Murphy almost single-handedly kept “SNL” alive in the early ‘80s.

He could make you feel as if you were in collusion with his down and dirtiest impulses, and he went further into brambly territory than the rest of the cast. But ultimately he was all about role-playing as a performance statement, not as a political statement. For him, the black-white divide was just a variation on the doubleness that divides all comics: the chasm between how they see themselves and how others perceive them.

Unavoidably, however, Murphy incorporated into his routines the wish-fulfillment fantasies of not only blacks in the audience but whites too, who enjoyed having the racial tables reversed. He became an instant movie star with “48 Hrs.” and “Trading Places” in large degree because he was so much smarter and flagrantly funnier than his white counterparts. Still pretty much a revue-sketch comic, he barely gave Nick Nolte and Dan Aykroyd the time of day in these films. He was a cocky monologuist, all mouth.

By the time he made “Beverly Hills Cop,” it was clear that Murphy also fancied himself a Stallone-style action hero. But whenever he went into his lawman routine he froze up and lost his specialness. For the first time in his career, a scene was stolen clean away from him -- by, fittingly, a comic, Bronson Pinchot.

As the diminished sequels to “48 Hrs.” and “Beverly Hills Cop” ticked by -- as well as lucrative but unmemorable fare such as “Harlem Nights” (where he, as co-writer/producer/director, cut his costar and idol Richard Pryor off at the knees), “Coming to America,” “Boomerang” and “Vampire in Brooklyn” -- a lot of people wondered why Murphy wasn’t making the earth move in his films the way he once did in television. He was no longer a rock star, he was just another movie star.

To some extent, this was an unfair expectation, for how many corrosive comic actors have ever triumphed for long over the homogenizing effects of Hollywood? Most of Murphy’s “SNL” colleagues (Chevy Chase being only the most conspicuous example) lost their edge in the movies and became entrapped in the muck of family entertainment.

But there were also rare exceptions, such as Aykroyd, especially in “Driving Miss Daisy,” and Bill Murray who developed into far more accomplished, far more mysteriously gifted movie performers. When you see Murray get inside his spooky silences and open himself up in “Lost in Translation,” you realize you’re watching a transformation that is at the very heart of acting.

It took a while for Murphy to achieve this kind of audacity and come into his own as an actor. Because he came out of stand-up and sketch comedy, he learned early on to coast on attitude; there was little continuity of character in his performances. In “Trading Places,” for example, we never see in the successful businessman the foul-mouthed vagrant he once was. It’s like watching two different actors.

But then there is “Bowfinger” where he plays, among other roles, a relentlessly paranoid movie star who is clearly a ruthless send-up of himself and his very public problems, or “Life,” where he plays with total authenticity a convict who ages 40 years in the course of the movie, or “The Nutty Professor,” where the pairing of decorous, fat-suited Sherman Klump and his testosterone-fueled alter ego, Buddy Love, defines the yin and yang of Murphy’s career (and also of African American personas in show business).

It’s one of the most startling comic performances on film, right up there with Steve Martin in “All of Me.” With his brown jacket and bow tie, his chuckling low voice and Oliver Hardy-like gracefulness of movement, Klump is determinedly old school. Murphy has a deep-down affection for this man. His Buddy Love, on the other hand, with his body-tight duds, hyperventilated hyena laugh and propulsive patter, is Murphy’s nightmare unveiling of his inner imp. As is often the case with Murphy at his best -- or even much lower down, as in “Norbit” -- what at first seems like blatant racial caricature turns out to be much more complex and emotionally nuanced.

As James “Thunder” Early in “Dreamgirls,” Murphy hasn’t split himself in two -- or three or five. He is playing a man who is triumphantly, tragically himself. He is also playing, for the first time in his career, an artist and perhaps this explains the ferocity and despair with which he attacks the role. Early is an ecstatic entertainer self-immolating in his own spotlight; the sheer sexual pleasure of performing has rarely been so well expressed.

This is why, to protest his new, sanitized self, Early drops his pants onstage in exultant protest. This is why, when he gets the word that his soul sound won’t cut it anymore, he shuts down right before our eyes. He pulls out the heroin and prepares for dreamland, and the ravaged look in his eyes tells us he’s not coming back. This is not Early’s final scene in the movie but it should be. It’s his poisoned valedictory.

Murphy is totally exposed in this film -- there are no fat suits to act as a poultice.

Sometimes actors reach so far inside themselves that they are left bewildered by what they have brought forth.

This performance as James “Thunder” Early is the latest, and most confounding, chapter in our long and complicated relationship with Eddie Murphy. He is only 45. May the complications increase.

*

Rainer is the film critic for the Christian Science Monitor and a frequent contributor to Calendar.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.