Meet today’s right-wing political football: The Ex-Im Bank

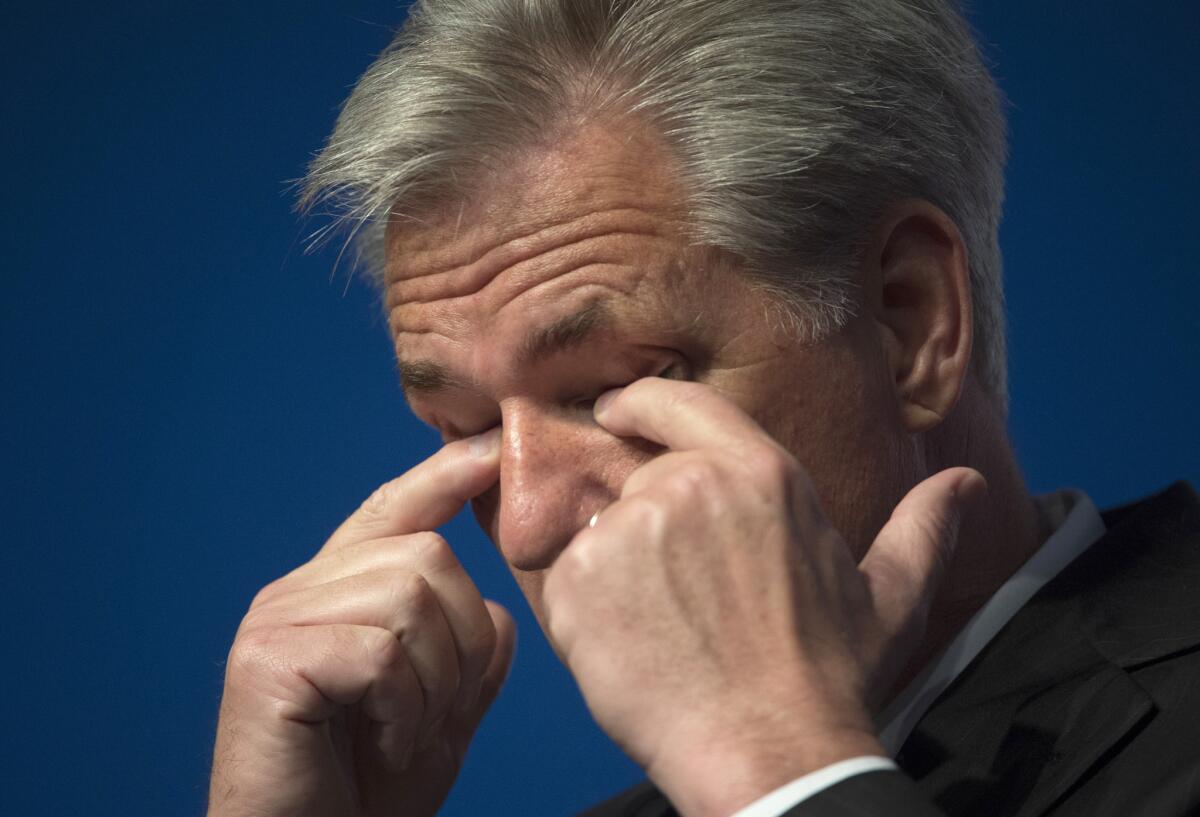

The new House majority leader, Republican Kevin McCarthy of Bakersfield, wasted no time this week establishing his bona fides with the right wing of his party. He went on “Fox News Sunday” to declare that he was in favor of shutting down the Export-Import Bank.

And among those Americans who might have been listening in, the cry went up: The what?

------------

FOR THE RECORD

June 27, 3:23 p.m.: An earlier version of this post misspelled the last name of Chris Chocola, president of the Club for Growth, as Chocula.

------------

Yes, the U.S. Export-Import Bank, a tiny warren of the federal government (its $20 billion in assets equal six-tenths of one percent of the federal budget) whose existence has become a huge rallying cry for the GOP right. Its extinction has been called for by the Heritage Foundation, the Club for Growth and other small-government advocates such as tea party types.

The House Committee on Financial Services under Rep. Jeb Hensarling (R-Texas), a sworn enemy of the bank, will hold a hearing on its future Wednesday. You shouldn’t be surprised if Hensarling makes hay out of recent reports that several Ex-Im Bank employees are being investigated for bribe-taking, but his real crusade is ideological.

Yet this isn’t just another battle of right versus left. The Ex-Im Bank’s supporters include the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the National Assn. of Manufacturers and lots of Republicans and Democrats in Congress. One supporter is Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield).

Oops. That was the old Kevin McCarthy, vintage 2012, when he was House Republican whip and voted with the overwhelming majority to reauthorize the Ex-Im Bank for three years. Now another reauthorization vote is upon us, and he’s noticed that the wind in the narrow political canyon known as House Republicanism is blowing the other way.

Because the bank will die if the House fails to vote in its favor, let’s take a step back and look at what it does.

The bank was created in the 1930s to provide loan guarantees to U.S. businesses or their overseas customers to lubricate the American companies’ export businesses. The idea was for the bank to step in when private banks held back.

That’s still its role. The bank doesn’t put up taxpayer money upfront, but rather loan guarantees, for which the recipients pay a fee; taxpayers are on the hook only if the borrowers default. The bank’s accounting (more on that in a moment) shows that it’s returned a profit to the government of $2 billion over the last five years. The projected profit over the next 10 years is $14 billion.

Most of the bank’s clients are small or medium-sized businesses, but the bulk of the guarantees by value go to a handful of big exporters such as Boeing and Caterpillar. The bank’s supporters say that activity helps preserve or create 1.3 million American jobs.

An example of how this works came up in 2001 testimony before a Senate committee. The subject was an Indiana company named CTB, which exported to Kazakhstan. “There is no way that any commercial bank wojuld finance Kazakhstan, financing for multiyear,” the committee heard. “Without Ex-Im Bank, that transaction would not have gone through.”

CTB, as it happens, was owned then by the family of Chris Chocola, who later became a Republican congressman from Indiana and now is president of the Club for Growth. What does he think of the Ex-Im Bank? It’s a “slush fund for market-distorting subsidies that pick winners and losers in the private sector,” he said last April. In other words, having been given a leg up the trade ladder by the Ex-Im Bank in the past, Chocola wants to pull up the ladder behind him.

Critics of the bank such as Hensarling contend that it actually loses money for the American taxpayer, but that the cost is shrouded in accounting tricks. But that’s misleading. They’re referring to the difference between standard federal budget accounting and “fair-value” accounting.

The distinction lies in how interest rates are estimated on future costs and benefits. Suffice to say that fair-value accounting calculates future risks differently, in part by computing them as they’d be computed by private, not government, lenders. That’s germane, Hensarling says, because export financing is something the private sector should do instead of government.

The problem, however, is that the Ex-Im Bank exists to step in when the private sector won’t -- as it did to help Chocola’s family company turn a profit, back before he learned the Club for Growth catechism. Even the Congressional Budget Office, which favors fair-value accounting, acknowledges that the method doesn’t count the “value of government programs to society” -- in other words, what government does that the private sector can’t or won’t do.

Hensarling’s critique also overlooks another argument in favor of the Ex-Im Bank: that it levels the playing field for American companies competing with foreign rivals that are heavily subsidized -- at far greater levels -- by their own governments. Boeing, for instance, has one competitor in its commercial-airliner business: Airbus, which receives up to six times as much in subsidies from its European government parents as Boeing gets from the U.S. (according to a 2012 ruling from the World Trade Organization).

And that’s where the rubber of the attack on the Ex-Im Bank meets the road: Here’s a small government program that helps thousands of businesses with hundreds of thousands of employees compete abroad. One would be impressed if the House aimed to take an objective look at the pros and cons of continuing the institution, based on real dollars and cents. But the debate these days is based on ideology, and in McCarthy’s case, partisan grandstanding. That’s some way to run a bank.

Keep up to date with The Economy Hub by following @hiltzikm

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.