Foreign nations push into space as U.S. pulls back

As NASA retreats from an ambitious human spaceflight program for the foreseeable future, foreign countries are moving ahead with their own multibillion-dollar plans to go to the moon, build space stations and even take the long voyage to Mars.

Although most of the world still lags far behind the United States in space technology and engineering know-how, other nations are engaging in a new space race and building their own space research centers, rockets, satellites and lunar rovers. Their ambitions are a declaration of their economic and technological arrival.

And it’s not just the Russians.

Later this year, China plans to launch into orbit the first phase of its own space station. The country has already launched six people into outer space and hopes to put a man on the moon sometime after 2020.

India is working on its second robotic trip to the moon, with plans to land a rover on the moon’s surface in two years. It wants to send a human into outer space by 2016.

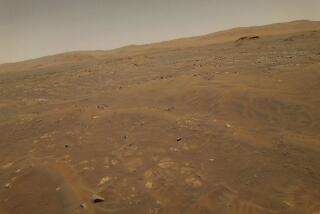

The European Space Agency is studying a trip to Mars by conducting a 520-day simulated voyage to the red planet. Six volunteers from various countries have been locked in isolation in a windowless mock spaceship, eating canned foods — except when they trudged through red sand and spiked flags into a mockup of Mars’ surface.

Iran plans to send a monkey into space in the summer, clearing the way for a man to follow. Countries such as Israel, Japan, North Korea and South Korea are busy building their own rockets and launching them from their own facilities.

Foreign countries are decades behind the U.S. in their space programs, said Jim Lovell, commander of the tumultuous Apollo 13 mission and a member of Apollo 8, the first mission to orbit the moon. But their human spaceflight programs are just beginning as the shuttle era comes to an end for NASA.

“There should be a hollow feeling in Americans’ stomachs when Atlantis lands,” Lovell said. “It’s hard to believe that other nations will surpass us in space technology. But if we continue down the road we’re headed, it can be done. I hope we turn it around soon.”

Russia, of course, has long been America’s closest competitor — and partner in more recent years — in space technology, and it continues to have a $7 billion-a-year space program. It shares command of the International Space Station.

By comparison, the Obama administration’s proposed NASA funding for fiscal year 2012 was $18.7 billion, but a House appropriations panel cut that to $16.8 billion last week, taking money out of NASA’s space exploration and science budgets, among other areas.

The panel also eliminated funding for the James Webb Space Telescope, the partially built successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, which is among the most successful NASA programs in history.

“It’s like a slap in the face for the American public who are watching their government abdicate leadership in space,” said Eugene Cernan, the last astronaut to walk on the moon, in 1972.

Now that the shuttle fleet is headed for retirement, the U.S. will travel to the space station on a Russian Soyuz rocket. Russia will charge NASA $63 million to carry an astronaut. And in a unforeseen development, U.S. astronauts are learning Russian so they can converse with the cosmonauts.

NASA wants private companies to one day take astronauts to the station, but that hardware isn’t yet ready. The space agency also has plans to build a new launch system to send humans on deep space missions, including a mission to land on an asteroid by the mid-2020s.

But the exact destination of future missions and a formal schedule has not been defined, and there is no guarantees for the financial commitment of the billions of federal dollars needed.

The space agency has long touted that its half-century in the space race has reaped lasting economic benefits and pushed forward the technological boundaries in a wide range of disciplines, including exotic materials and medical applications. The program has also helped motivate a generation of youth to pursue careers in science and technology.

But as the luster of the Apollo moon landings gave way to a repetitious space shuttle program, human spaceflight became routine and almost mundane for many Americans. As a result, Congress perceives little public zeal to proceed with ambitious space travel.

“It is sad to see the end of the shuttle with nothing to go onto,” said Jeremiah Pearson, former NASA associate administrator for human spaceflight. “We are going to become a Third World nation in spaceflight.”

That is not the case for China, whose manned Shenzhou missions received constant live TV coverage and significant events during the missions such as the launch and recovery made front-page news in the nation.

The Chinese space budget is not published and is difficult to calculate. John Pike, executive director of GlobalSecurity.org, estimates that it is more than $5 billion.

Last year, the Chinese government began building a 3,000-acre space center on Hainan Island in the South China Sea, its fourth launch facility. China, striving to become a global economic powerhouse, has touted the economic benefits of the program.

“There’s a very organized propaganda effort on behalf of the Chinese government about the program,” said Gregory Kulacki, a member of the Union of Concerned Scientists who is based in Beijing. “They see the space program as a source of national pride.”

In 2003, China became the third country to send a human into space. Three years later, it sent a probe to the moon. The country now has 21 astronauts, including two women. China is also preparing to open a space station in 2020 — the same year that the International Space Station is scheduled to shut down and de-orbit.

“The Chinese have major aspirations in space,” said Marion Blakey, chief executive of the Aerospace Industries Assn. trade group. “It would be a terrible thing to watch their backs as they go into deep space while we are grounded.”

China’s regional neighbors have also taken note.

India has doubled its annual space budget over the last five years to $1.3 billion, said Bharath Gopalaswamy, a senior research scholar at Cornell University and Indian space analyst.

The country spent about $100 million when it sent a 3,000-pound probe, Chandrayan Pratham, or “First Journey to the Moon,” to orbit the moon in 2008. Now, Indian engineers and technicians are building a rover to land on the moon’s surface for the country’s second moon mission, and is collaborating with the Russian government on the program.

India is also setting up a training center in the southern part of the country for astronauts. It plans to launch its first human into space by 2016, Gopalaswamy said.

“India realizes that they are not first in space,” he said. “But it is important for India to show that it can build space technology and innovate.”

Meanwhile, Iran, which has already launched a rat, turtles and worms into space, has plans to lift a monkey by this summer inside a capsule atop its Kavoshgar-5 rocket. The country wants to put a man into orbit by 2021.

For foreign nations, “space travel is a projection of power and pride,” said Marco A. Caceres, space analyst for the aerospace research firm Teal Group Corp. “Can you imagine if the Chinese planted the flag on the moon? Americans would be envious, uneasy and questioning how it happened.”