Column: Kaiser Permanente CEO Bernard Tyson’s death comes at a time of transition for the huge system

Bernard J. Tyson, chairman and CEO of the giant nonprofit Kaiser Permanente health system, died suddenly Sunday morning, Kaiser announced.

“Bernard was an exceptional colleague, a passionate leader, and an honorable man. We will greatly miss him,” said Edward Pei, chairman of the executive committee of the Kaiser board. The board named Executive Vice President Gregory A. Adams as interim chairman and chief executive.

Tyson’s death comes at an especially sensitive moment for the health system.

We truly worked together to make Kaiser the best place to receive and give medical care. There was true collaboration to establish an appropriate balance of power between labor and management.

— Healthcare union leader Sal Rosselli on Kaiser’s Bernard Tyson

Kaiser reached a contract settlement with 85,000 workers, averting a threatened strike, just weeks ago. And it was facing a five-day walkout by some 4,000 mental health clinicians starting Monday. The walkout by members of the National Union of Healthcare Workers was postponed, union officials said Sunday, in observance of Tyson’s passing. A new date was not announced.

Both disputes placed the system’s 20-year reputation for collaborative labor relations in doubt.

Few healthcare entities play as large a role as Kaiser in California and across the nation. Kaiser is both a health insurer and health provider, owning its own hospitals and clinics and setting forth treatment protocols for its professional workforce.

Kaiser’s labor management partnership was revolutionary when it was launched in 1997. But can it survive today’s union negotiations?

Traditionally, the system made a distinction between conventional medicine and “Kaiser medicine,” based on the argument that its integrated approach to patient treatment was superior to the fragmented structure of care outside the Kaiser umbrella.

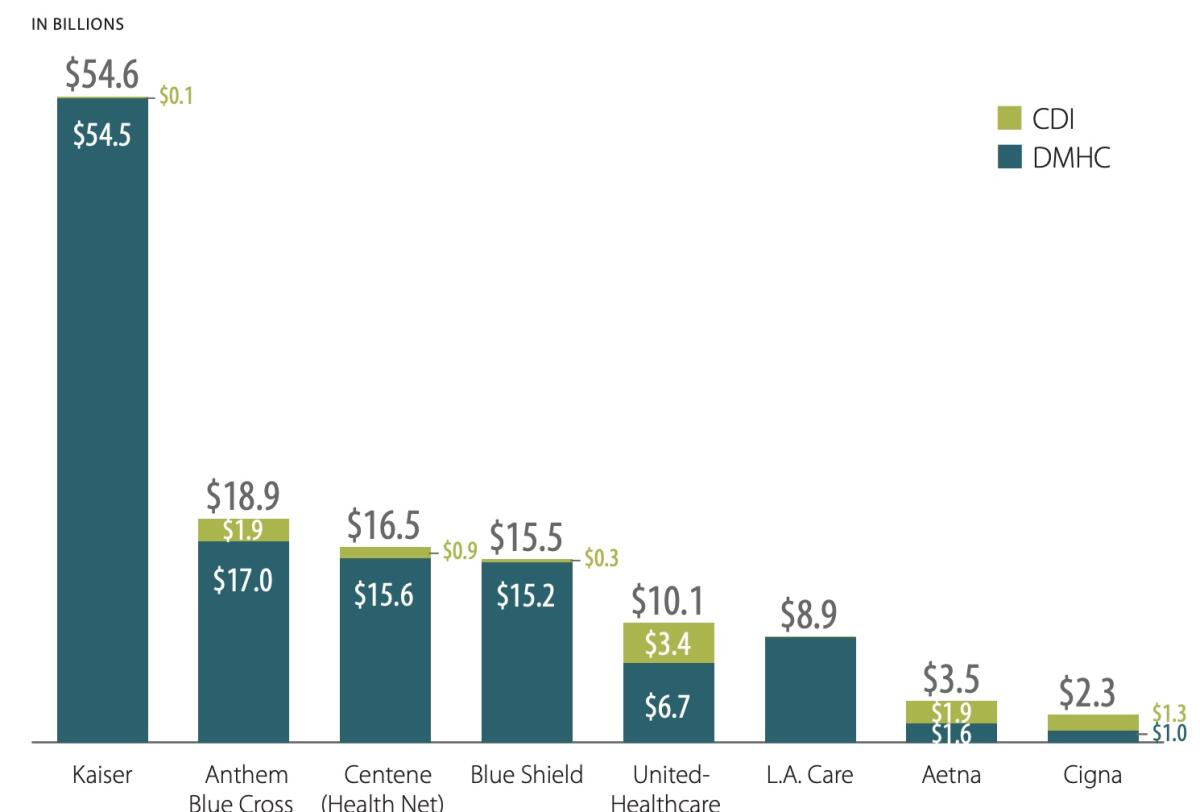

Kaiser led all other insurers in California enrollment, at 8 million members in 2017, and in share of California revenue, with $54.6 billion.

A three-decade veteran of Kaiser management, Tyson, 60, presided over an appreciable increase in the Kaiser system’s enrollment and financial strength since becoming CEO in 2013 and chairman a year later. The organization grew from 9.1 million members and annual revenue of $53 billion in 2013 to 12.3 million members and $79.7 billion in revenue at the end of 2018.

Tyson’s posts placed him at the center of a healthcare economy undergoing wrenching change. His voice was important. In 2017, when several for-profit insurers such as Aetna were bailing out on the Affordable Care Act, Tyson made clear that Kaiser was intent on continuing to participate in the ACA’s exchanges.

He took particular exception to a remark by Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini that the exchanges were in a “death spiral.”

“I would not use that term,” Tyson said, “because we have 20-plus million people getting access to care through the front door. That’s progress.” The Obamacare markets have since stabilized and now are producing profits for many participating insurers.

Yet in recent years a pioneering labor-management partnership reached at Kaiser in the mid-1990s, which is often given credit for dramatic improvements in Kaiser’s patient treatment and financial strength, has begun to fray.

As it happens, Tyson “was a Kaiser executive who helped establish the labor-management partnership,” says Sal Rosselli, president of the National Union of Healthcare Workers. In that period, the mid- to late 1990s, Rosselli was associated with United Healthcare Workers West, an affiliate of the Service Employees International Union.

“We truly worked together to make Kaiser the best place to receive and give medical care,” Rosselli told me. “There was true collaboration to establish an appropriate balance of power between labor and management.”

Bernie Sanders has triggered another debate over the frequency of medical bankruptcy, but he’s mostly right.

The recent labor issues have turned partially on questions of how Kaiser deploys its massive resources. The system reported net income of $2.5 billion on operating revenue of $79.7 billion last year, compared with net income of $3.8 billion the year before — a decline it attributed partially to “volatility in the investment markets.”

The system also reported reserves of $31.6 billion, a metric relevant to its role as a health insurer, in 2017.

Those figures have turned the spotlight on Kaiser’s spending, which includes construction of a new $900-million headquarters building, on which ground is to be broken in Oakland next year. The system also has made a bid reported to be $295 million for naming rights to the district around the Golden State Warriors’ new basketball arena in San Francisco. (The location would be called “Thrive City,” a reference to Kaiser’s advertising catchword, “Thrive.”)

And the system is planning to open its own medical school next year in Pasadena, waiving all tuition for the first five classes of students.

The medical school plan “suggests how well they’re doing,” says Anthony Wright, executive director of the consumer group Health Access California. “They’re looking not just at next year’s returns, but at educating future generations. But as much as that is probably a very good investment in the future of California’s healthcare system, it’s also fair for the people who’ve been paying premiums to Kaiser to say, where does that money come from?”

An anti-spending group issues some scary numbers about Medicare for all, but leaves out some key considerations.

Tyson’s own compensation, which reached $16 million in 2017, the latest year reported, became a flashpoint in the recent labor conflict with the SEIU-UHW, which had threatened to call some 37,000 members out on strike if a contract had not been reached by Oct. 1. A tentative contract was reached on Sept. 25, covering 85,000 employees.

During the contract negotiations, the UHW weighed Tyson’s pay against what it said was Kaiser’s relatively low level of enrollment of low-income Medi-Cal members compared with other nonprofit hospital groups. Kaiser disputed the union’s statistics.

The current dispute with clinicians concerns Kaiser’s mental health services, which the union says lag far behind services for patients needing physical treatment. The union says mental health services are chronically understaffed, resulting in appointments being deferred for as long as two to four months for enrollees requiring prompt treatment.

“Our union has demonstrated to them that their mental health system is broken,” Rosselli says. “We’re trying to help them understand that they should collaborate with their mental health clinicians to do the same thing we accomplished in the late ‘90s on the medical side.”

Kaiser asserts that it has increased its staff of mental health therapists by 30% since 2015, a period in which patient enrollment increased by 23%, “despite a nationwide shortage of mental health care professionals.”

The system’s shortcomings in mental health services have been documented in the past. The state Department of Managed Health Care fined Kaiser $4 million in 2013 for “serious deficiencies in providing access to mental health services,” including wait times for appointments that exceeded state standards.

Rosselli faults Tyson for failing to take the issue in hand. “He listened to people who were in denial about the mental health system being broken and inaccessible,” he says.

The company provided no other details in its announcement of Tyson’s death. Tyson served on a number of corporate and other boards, including Salesforce.com Inc. He was a former board member of Occidental College. He is survived by his wife, Denise Bradley-Tyson, and three sons, Bernard J. Tyson Jr., Alexander and Charles, the Associated Press reported.