Martin Luther King Hospital is in jeopardy. This critical medical facility must get the funding it needs

- Share via

Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital forms the cornerstone of Los Angeles County’s public investment in the health and well-being of millions of residents who have few other options for medical treatment. The private facility has been a remarkable success since it opened 8½ years ago, replacing a notorious public hospital that closed after an endless series of medical and management failures.

Now, the new hospital is also in jeopardy, not because of the quality of medical care or management, both of which have received stellar reviews.

Just a few months after leading the historic voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., the Rev.

The problem is a funding structure that relies on supplemental payments from the state and the county but does not take inflation into account. The hospital is also a victim of its own irreplaceable role in the community. So many South L.A. County residents are uninsured or underinsured and therefore do not visit outpatient clinics — few of which exist in that underserved part of the county anyway — that their medical conditions worsen until they have to come to the hospital.

MLK’s emergency department serves nearly four times as many patients — sometimes 400 a day — as the 110 daily visits expected when the hospital opened in 2015. The lack of insurance and reimbursements resulted in a loss of $42 million in the budget year that ended in June.

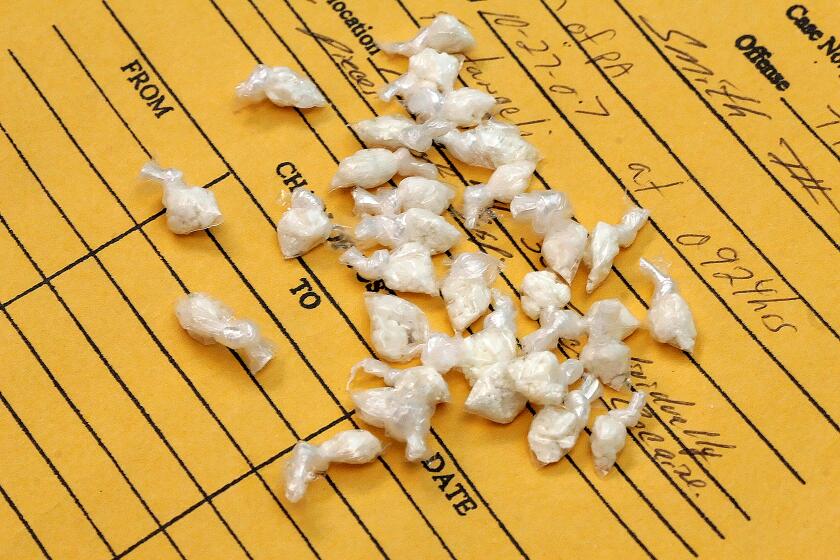

America responded to the 1980s crack epidemic with police and prisons instead of public health. Now look where we are.

Restructuring the supplemental payments should be a no-brainer, except for two barriers. First, California no longer enjoys excess revenue and in fact Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed a 2022 bill that would have provided an important ongoing state financial boost.

And second, memories are short. So short, in fact, that a new generation of lawmakers (even those representing the hospital’s service area) may have forgotten what a disaster it was for their constituents to be mistreated by the former hospital, and then to be left untreated during the decade between its closure and the new facility’s opening.

So some reminders are in order. The former hospital, formally known as Martin Luther King Jr./Charles Drew Medical Center (and informally as “Killer King”), opened in Willowbrook in 1971 in the wake of unrest following King’s assassination in 1968. Its construction and operation by Los Angeles County was an acknowledgment of the shocking lack of basic medical care in what was then a largely Black community.

The hospital became especially noted for its trauma unit, which treated an inordinate number of gun violence victims.

But inadequate county oversight and management contributed to low standards of care and, ultimately, closure in 2007. It was the most consequential failure of the nation’s largest county government — and the state — to meet their basic responsibility to constituents.

We need L.A. County’s Care First, Jails Last Alternatives to Incarceration program moving forward, fully funded.

The plan to replace it and return first-class medical service to the community was a stroke of genius. The new hospital is privately run, which eliminates some of the management problems created when medical personnel who failed to meet professional standards were protected by the county civil service system. But it was built with county funding on county land. Physicians are provided by the University of California campuses. The facility is located on a medical campus that includes a number of complementary county-run health services, some of which are cutting-edge, including medical urgent care, psychiatric urgent care, a short-term recovery or “sobering” center, recuperative care and a public health center.

Taken together, these and other services represent the sort of investment in public health, mental health and medical care that county government has made the foundation of its “care first” mission in the last decade. The state ought to back these investments with commitments of its own.

The county Board of Supervisors has before it on Tuesday a motion to quickly consider options for keeping the hospital afloat. State lawmakers, when they reconvene in January for the second year of their two-year session, should do likewise. There are many competing interests vying for a piece of the state’s tight budget, but essential medical services for millions of Southern Californians should be at or near the top of the list.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.