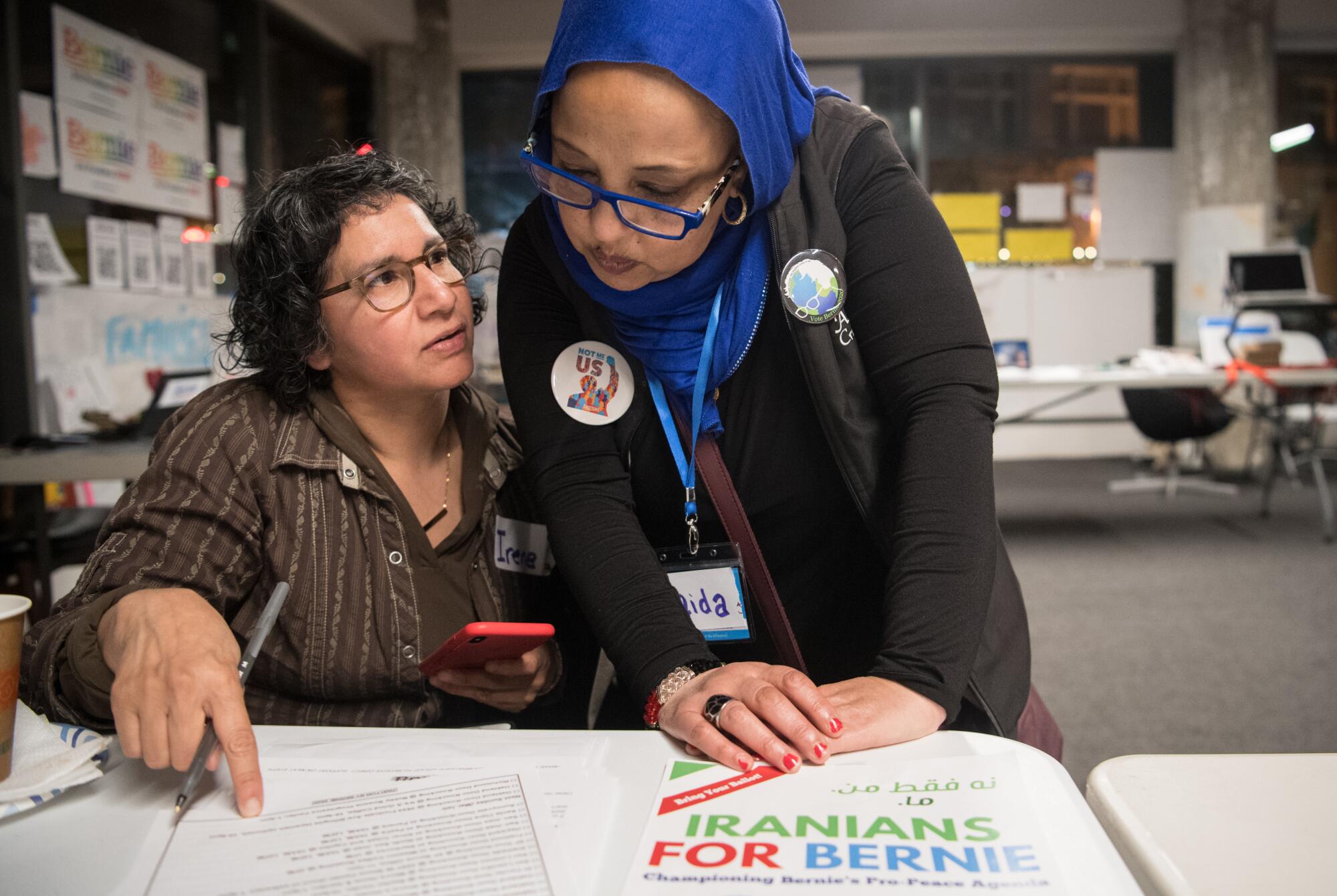

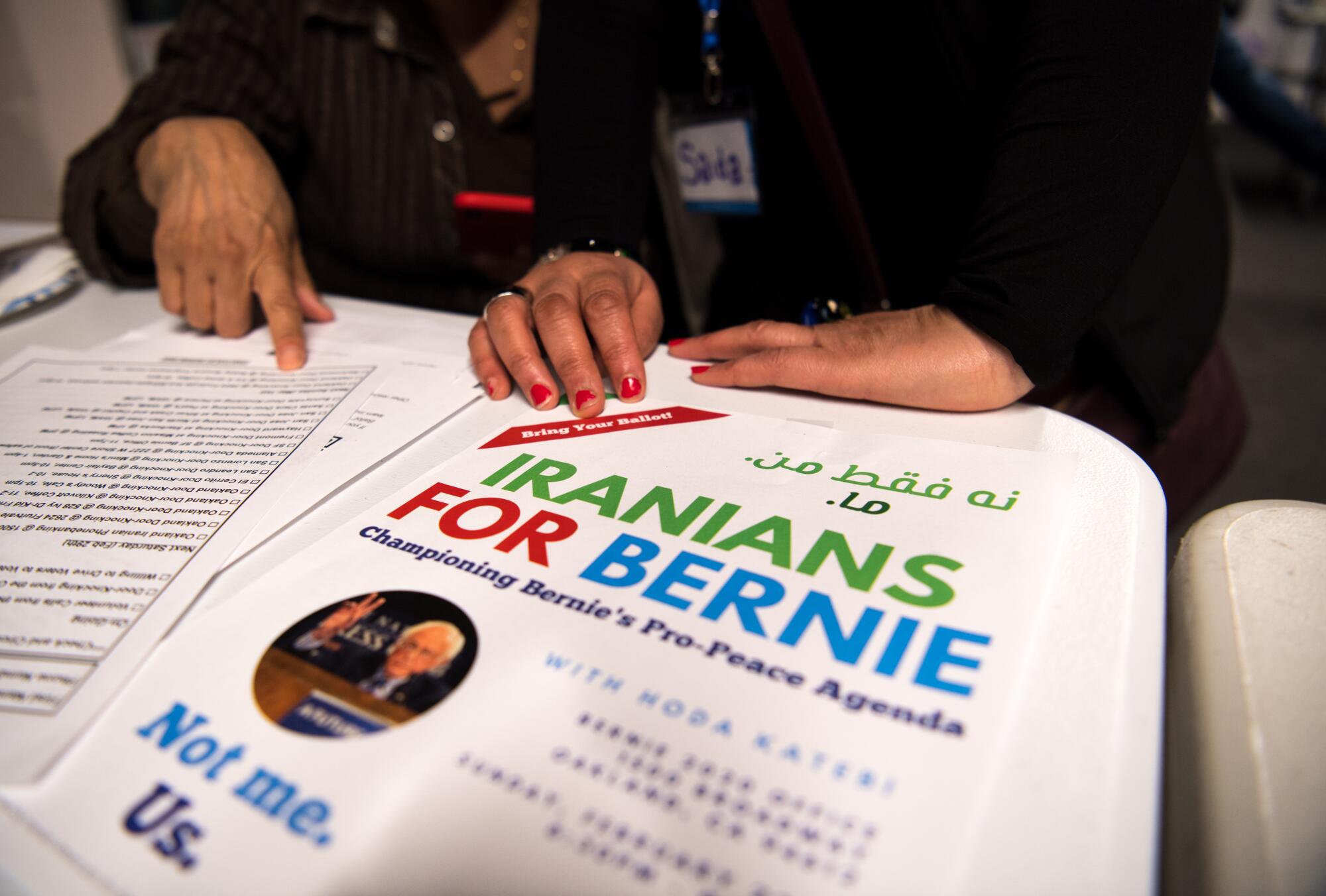

Behrang Barzin stood at the back of Sen. Bernie Sanders’ downtown Oakland campaign office, waiting to address the “Iranians for Bernie” gathered to learn more about supporting the presidential contender.

The mostly young crowd made small talk as they reached for Middle Eastern sweets and buzzed around the tea station. But the upbeat mood over Sanders’ candidacy belied Barzin’s feeling that many politicians overlook California’s Iranian American community.

“We’re underrepresented,” Barzin said. “We have resources. We have money. But people don’t acknowledge that we’re here. We don’t know the game well enough to get involved, and that’s why people don’t reach out to us.”

The February forum, organized by grassroots Iranian and Muslim groups in California, offered a rare chance for the more than 120 people gathered there to participate in a tailored discussion hosted by a presidential campaign. Several attendees said they hadn’t heard of a similar event during previous election cycles.

To come out on top in California’s primary, Democratic contenders must appeal to a patchwork of ethnic constituencies, among them the large Iranian American population that spans San Diego, Los Angeles and the Bay Area. This year’s shift in the state’s primary election calendar from June to next week’s Super Tuesday blitz has incentivized candidates to ramp up their efforts to attract not only liberal voters writ large, but also the diverse pockets that compose much of the state’s electorate.

Barzin backed Sanders in 2016, but the 38-year-old business owner had debated supporting former Mayor Pete Buttigieg this time around.

Then, about a month ago, a volunteer canvassing for Sanders knocked on the door of his Berkeley home and invited him to an antiwar protest in San Francisco. The rally came on the heels of the Jan. 3 U.S. drone strike that killed Iranian Gen. Qassem Suleimani and the subsequent military escalation between the two nations.

Following the strike against Suleimani, Sanders posted a message on social media in multiple languages, including Persian: “End endless wars.”

After attending that protest and a couple of other Sanders campaign events, Barzin cast his ballot for the senator several days ago. Yet his vote wasn’t based solely on Sanders’ antiwar stance. Earlier this month, Sanders had posted another photo, with a Persian text that outlined what would be covered under his “Medicare for all” plan, including dental work and devices such as hearing aids.

“I don’t just look at it through an Iran window,” Barzin said. “I think he’ll be great for the economy. I’m a small-business owner, and if my employees get healthcare I don’t have to pay $500 each for them. I can put that money toward raises and back into my business.”

Although some presidential hopefuls are beginning to court this increasingly politically active community, divisions within the diaspora pose a challenge to those aiming to capture Iranian votes — especially in L.A. An estimated half a million Iranian Americans live in Southern California alone. Like other ethno-national groups, their political views reflect a complex calculus; there’s no single issue or one-size-fits-all pitch to attract Iranian American voters.

Sahar Sadeghi, an assistant professor of sociology at Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania who researches the Iranian diaspora emphasized that Iranian Americans are not monolithic in their political leanings. Some, like those attending the Sanders forum in Oakland, identify as progressives, while others see themselves as moderate Democrats who would support a candidate closer to the center.

The southern half of the state — centered on enclaves of Orange County, Los Angeles and San Diego — is home to a conservative Iranian contingent that tends to back President Trump, his withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and his tough talk against the Islamic Republic.

“Iranians in L.A. have much more polarized views than those in Northern California,” Sadeghi said. “The Iranian diaspora in L.A. tends to have a few demographics that Northern California does not have as much of. One is the presence of Armenian Iranians and Iranian Jews. That in and of itself adds a new dimension.”

Amy Malek, an anthropologist and researcher at Princeton University studying the Iranian diaspora, agreed that “there’s not a unified voice” that speaks politically for all Iranian Americans. That lack of cohesion, both on domestic issues and U.S. foreign policy toward Iran, tends to prevent the diaspora from aligning in a solid voting bloc, Malek added.

At least one other Democratic candidate is considering reaching out to Iranian American voters: billionaire Michael R. Bloomberg, who has spent more than $124 million on advertising in the 14 Super Tuesday states.

Democratic strategist Bill Carrick said that appealing to California’s many ethnic groups, including Iranian Americans, requires politicians to develop a nuanced knowledge of the communities that live here.

“Most people campaigning for the first time here in California don’t understand the depth and complexity of the diversity here, so there is a tendency to think of it as Latinos, African Americans and Asians, and that’s sort of it,” he said. “But we have communities like the Iranian community that have come here fleeing a government they didn’t like; we have a large Armenian community.”

Anna Bahr, the Sanders campaign’s California communications director, said the candidate’s staff has relied on its diverse volunteers and supporters “to help us tap into communities that don’t often get attention from presidential campaigns.”

The 78-year-old Vermont senator has a team of more than 250 “language justice volunteers” from across the country who translate tweets and graphics, according to his campaign.

“Iranian Americans care about a lot of different issues,” Bahr said. “They care about affordable healthcare, accessible housing. They want to make sure their grandchildren have a planet to live on.”

Nazli Parvizi, Bloomberg’s California lead for constituency groups, said that his team is exploring running Persian-language ads in local media, such as Jewish outlets read by the state’s large Persian Jewish community. They also are looking at placing ads in regional newspapers in an effort to reach other diverse communities, such as the Chinese and Vietnamese diaspora, she said.

“We have Latino outreach, we have African American outreach,” she said. “We don’t need money, but we want your influence.”

Political divisions within the Iranian diaspora often also reflect generational differences among those who fled the 1979 Islamic Revolution, immigrated after the 2009 Green Movement or were born in the U.S.

Those distinctions can also inform levels of civic engagement: Younger Iranian Americans are more likely to run for public office or work in politics, experts say. During the 2018 midterm election cycle, three women became the first Iranian Americans elected to the New York, Georgia and Florida state legislatures.

Afshine Emrani, a 52-year-old cardiologist, sees this generational gap play out every day, whether through his children’s eyes or by listening to the patients who step into his Tarzana office.

“I’m more to the right of center,” said Emrani. “My kids, going to a Jewish school, are being taught mostly liberal values. They get some conservative values from me and my family because we are older, but their education tends to be mostly liberal.”

The community, he added, has only recently become more politically active.

“We have a lot of opinions, but don’t act on them,” he said. “I think the people who actually show up are younger people. They have gone out of that mentality of ‘I have to be a doctor or lawyer or engineer to make a living or make my mom happy.’”

Having initially supported Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton in 2016 before voting for Trump, Emrani believes the current president can help restore Iran “to the greatness it had before” through his unconventional, “cowboyish” approach to politics.

Despite that, he doesn’t support all the Trump administration’s policies, such as the travel ban that restricts the entry of visitors from more than a dozen countries, including Iran, to the U.S.

“It’s not what happens to Iran so much as it’s the general policy toward the Middle East that makes a difference,” Emrani said. “Is this somebody who is going to appease whatever regime is there and give them what they want to make them our friends like Obama did, or is it someone who says, ‘This is my policy and I’m going to stand my ground.’”

A 2019 poll commissioned by the Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian Americans (PAAIA) found that foreign policy, including the U.S.-Iran relationship, ranked first among issues that the community will consider when voting in federal elections, outranking the economy and jobs, national security, education and healthcare.

California’s primary election is March 3, 2020. Here’s what you need to know about the presidential candidates and voting on Super Tuesday.

“You see circumstances where liberal Democrats might be more hawkish toward the Iranian government than a Republican, and I think it’s just based on their own personal perceptions and views and not party politics,” said Morad Ghorban, PAAIA’s director of government affairs and public policy.

Hoda Parvinchiha and her husband aren’t as politically active as they’d like to be. Her activism comes in waves, she said, when tensions in the community reach a fever pitch, or world events put the focus on Iran. After the Trump administration’s travel ban first went into effect in 2017, she joined others in protesting at Los Angeles International Airport. She took her daughter, then 7 months old, with her.

Sitting inside her Mission Viejo home on a recent weekday, Parvinchiha said she hopes to become involved not just when the spotlight is on Iran. The 38-year-old is thinking of volunteering for Sanders’ campaign, spending some of her spare time phone banking for the candidate with friends and family.

“It’s not just about international politics; it’s other things he believes in, like healthcare for all,” she said. “He’s super consistent. If it wasn’t him, I like Elizabeth Warren.”

Parvinchiha said she’s noticed Sanders’ social media posts in various languages, but it wasn’t the Persian messages that stayed with her — it was the act of posting in other languages in general. The move, she said, showed that the candidate “acknowledges that America is a melting pot.”

But that type of outreach may not be enough to hook all Persian voters.

“We fight amongst ourselves. It gets so heated, even in the family,” Parvinchiha said as her daughter flopped onto the couch and sat in her lap. “Some things they say bring up so much, and that’s how it plays out in the community too.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.