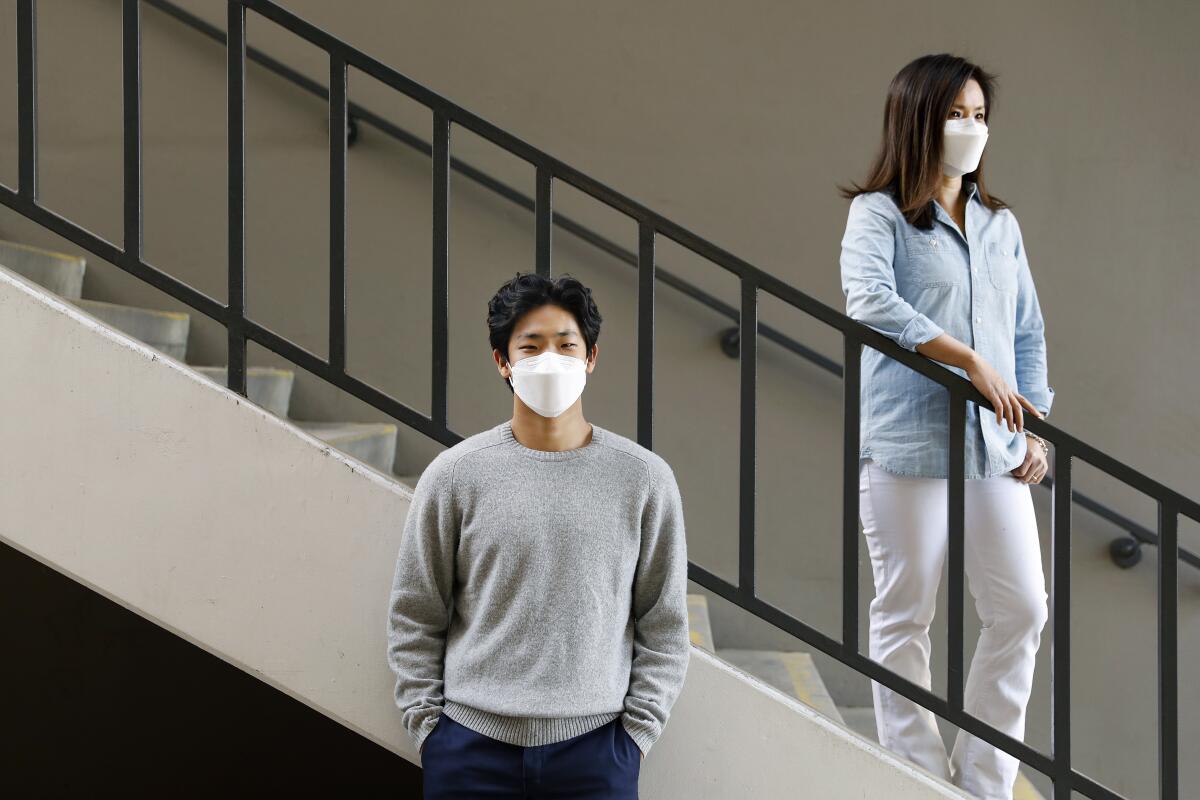

Some Asian Americans and immigrants wore masks readily. In a brutal election year, it made them heroes, targets, prophets

James Wang was among the Asian immigrants who donned a mask when the coronavirus still seemed a distant problem.

As the pandemic worsened in the U.S., he watched his native Taiwan beat back the virus without shutting down its economy.

While many Americans eventually grew accustomed to covering their faces, others refused to mask up, playing down the threat of the virus and even calling it a hoax.

On massive billboards advertising his law practice, Wang updated his photo to include a mask over his face — and received emails critical of the move from a few people who accused him of fear-mongering.

“It’s just a mask,” said Wang, 43, who lives in Diamond Bar and came to the U.S. when he was 10. “I can’t believe how polarized it became.”

For Asian immigrants in the San Gabriel Valley and elsewhere, the pandemic has become a moment of reckoning, exposing the weaknesses of their adopted country.

Raised on an ethic that elevates family and community above the individual, as well as a strong belief in science, many find it difficult to fathom why anyone would view masks as an infringement on personal freedom — let alone why President Trump would encourage that attitude.

In January and February, Asian immigrants attracted puzzled glances for covering their faces. Later, they became targets of racism, as Trump and others played up the virus’s Chinese origins.

Immigrants come to this country hoping life will be better. This year, the U.S. is unquestionably worse off than Asia, as illnesses, deaths and shutdowns pile up.

Asian Americans in California have not died from the virus at disproportionately high rates, as Black and Latino residents have.

But they are suffering like everyone else from school closures and social isolation. Small businesses, always a toehold to success for immigrants, have been devastated, with Asian-owned restaurants, dry cleaners and nail salons shuttered or barely staying afloat.

In Taiwan, people are enjoying rock concerts in crowded arenas, and kids are attending school. In South Korea, despite a recent uptick, coronavirus rates remain far lower than in the U.S.

“It makes me sad to see the denial, because our healthcare workers are at great risk helping COVID patients,” said Soo Kim Choi, 49, a South Korean immigrant who lives in La Cañada Flintridge. “I talk to healthcare workers frequently, and if people would listen to them, listen to the science and wear masks, we’d be in a much better place.”

Masks have long been customary in South Korea and other parts of Asia — to protect others when the wearer is sick, or as a shield against pollution. Not everyone engages in the practice. But even before the pandemic, it was common to see masked people on the subway or in the streets.

Growing up in Seoul, Choi and her family were not among those who masked up when they had a cold or flu. But she was raised to respect science and to consider the good of the community, she said.

In February, Choi noticed that shoppers and employees at her favorite grocery store, Seoul Market in La Cañada Flintridge, were wearing the Korean equivalent of an N-95 mask. In the face of a dangerous new contagion, it was second nature for Asian immigrants to put up with a little inconvenience to protect themselves and others.

“When you live in a small country where outbreaks happen quickly, you’re more sensitive, at least first-generation folks are, about taking precautions and trying to stay safe,” said Choi, a former banker and small business owner.

Not only did Choi don her own mask early on, but she and her youngest son embarked on a project to fix a batch of old N-95 masks donated to Glendale’s USC Verdugo Hospital.

Gavin Choi, a senior at La Cañada High School, created a GoFundMe account in June to replace the elastic bands on the masks.

He raised more than $2,000 and replaced 11,000 bands with the aid of volunteers.

Though he was born in the U.S., Gavin Choi is familiar enough with Korean culture to see contrasts.

“This has always been about following the science, listening to the experts and doing what’s best not just for you, but the people around you,” said Choi, 17, an Eagle Scout who hopes to join the military. “I’m proud of my Korean culture, that we believe in being considerate and thoughtful.”

When Asian Americans like Wang and the Chois began sporting masks in supermarkets and stores throughout the San Gabriel Valley, other residents were mystified. Some said Asian Americans were in “a panic.”

By mid-March, with public health recommendations piling up and most retail stores requiring masks, the early adopters seemed prophetic. In L.A. County, masks are now ubiquitous.

But the same has not been true in some other places, including parts of Orange County.

“For a while people looked at Asians and wondered, ‘What’s this weird thing they’re doing?’” said Emma Teng, a professor of Asian Civilizations at MIT. “Slowly, it went from being something strange and foreign to being gradually accepted, although still quite controversial.”

In Huntington Beach, hundreds of maskless demonstrators excoriated government orders to wear face coverings and socially distance as anti-American, fascist and an infringement on their rights. In Washington, Trump and others in his circle came down with COVID-19 yet continued to gather indoors without masks.

Elsewhere, Asian Americans no longer stood out for their masks. But they became targets for another reason — the perception, fanned by Trump, that China, and by extension anyone who looked Asian, was responsible for a pandemic that was killing Americans and crippling the economy.

Stop AAPI Hate, a tracking site created in March, documented 245 racist incidents against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in L.A. County between March and October, with 76% being verbal assaults.

Some of the vitriol involved the coronavirus.

In one incident described on the site, a woman yelled at a mother and son in a Los Angeles park: “Get off these steps! Do you know about the Chinese disease?”

In another, a woman said to an Asian American person at an Eagle Rock shopping plaza: “Oh my God! China brought the virus here!” followed by “Oh my God! Please don’t give me the virus!

For Asian immigrants, COVID-19 was not the first public health scare involving a deadly coronavirus. San Gabriel City Councilman Jason Pu points to the SARS outbreak of the early 2000s in Asia as a wakeup call, with immigrants in the U.S. closely following the news back home.

“When you talk about COVID-19 and safety precautions like wearing a mask, the conversation often turns back to SARS and what families learned then,” said Pu, who was born in Arcadia and has roots in China and Taiwan.

The SARS experience also helped prepare Asian countries like Taiwan and South Korea for the next viral outbreak. When COVID-19 hit, they quickly closed their borders and implemented strict contact tracing and quarantining. Few people complained about wearing masks.

Taiwan, with a population of nearly 24 million, has had fewer than 800 coronavirus cases and seven deaths. By comparison, Los Angeles County, with about 10 million residents, has had more than 670,000 cases and more than 9,000 deaths.

The contrast between Asia and the U.S. has been stunning and disappointing to immigrants who uprooted themselves and moved an ocean away with high expectations for the richest country in the world.

While the U.S. has offered some economic assistance, the aid has not been as robust as in South Korea and Japan, which Pu said has left many of his city’s small businesses, including some owned by Asian immigrants, “just hanging on” as they await more government help.

Perhaps most incomprehensible to many Asian immigrants is the refusal by some Americans to wear masks and follow coronavirus safety guidelines.

“What has surprised a lot of the Asian immigrant community has been the selfishness of people who won’t take safety precautions because it’s an ‘infringement’ of their rights,” Pu said. “Wearing a mask is the bare minimum you can do.”

Rosemead resident Chong Taing, who is of Chinese-Cambodian heritage, wonders what would have happened if Trump had set an example by wearing a mask early on, instead of disparaging the practice.

Perhaps the United States wouldn’t be leading the world in infections and deaths, and the president would be preparing to transition into a second term, not contesting the election results.

“A lot of this was avoidable,” said Taing, 40, who works in sales. “I don’t want to sound mean, but a lot of people lost their lives, their jobs, their social lives, missed family gatherings, church services and more because they refused to put on a mask.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.