Eitan Peled has a collection of new airport selfies, but he hasn’t traveled anywhere recently.

The photos document asylum seekers’ final moments in San Diego before they board planes to reunite with loved ones they’ve spent sometimes years trying to reach. In those moments, the new arrivals are finally at ease, letting go of the nerves that rode with them even in the van to the airport.

Peled uses the pictures to keep track of days that have blurred together as he and other Jewish Family Service staff push themselves to give as much support possible to asylum seekers passing through the organization’s migrant shelter program.

While unaccompanied migrant children recently apprehended crossing the border are to arrive soon at the San Diego Convention Center, asylum-seeking families have been sheltered in the city for years by Jewish Family Service. As the number of asylum seekers released into the area increased this month, the shelter put out a call for more staff and volunteers to help hand out meals, make travel arrangements and guide newcomers through San Diego’s airport.

In the meantime, shelter staff are working around the clock to rebuild the shelter’s capacity after months of decreased need during the pandemic, all while navigating the complications of COVID-19 precautions.

“Every time we travel a family out, that’s another family that we can accept,” Peled said.

That knowledge keeps him working seven days most weeks.

The shelter first opened in late 2018, when the Trump administration stopped immigration officials from helping asylum-seeking families make travel arrangements to reach their final destinations in the United States and began releasing those families by the busload at transit centers with no support.

When the pandemic began and the Trump administration issued an order, known as Title 42, which authorized officials to immediately expel border crossers, the number of families coming to the shelter dwindled.

But beginning in November, occupancy at the shelter — restructured post-COVID to hotel-style rooms instead of the communal sleeping space from before the pandemic — slowly increased again.

In February, Jewish Family Service began receiving asylum seekers who had been placed in the Trump administration’s so-called Remain in Mexico program, known officially as Migrant Protection Protocols, or MPP. As President Biden winds down the program, asylum seekers with active immigration court cases in MPP are being let into the United States in several locations, including the San Ysidro Port of Entry.

At first, the MPP asylum seekers came in groups of 25 per day. That has increased to about 50 per day.

Then, in March, without warning, the Border Patrol began sending the shelter migrants who had been apprehended as far away as Yuma, Ariz.

While President Biden has taken some steps to change Trump’s asylum policies, many are still in effect to keep asylum seekers out of the country they hope will protect them. Those policies are not being applied evenly.

As of March 25, the shelter has received more than 2,000 people this month. That’s up from 490 in all of February and 144 in January, according to Kate Clark, an attorney with Jewish Family Service.

The nonprofit wasn’t staffed for such an increase, and that has meant long days for Clark, Peled and the whole shelter team. The service is glad to be helping more people, but needs more staffing to make sure that care stays at the quality it should be, Clark said.

“It’s not a crisis,” Clark said. “It’s just a situation.”

While some shelter staff are transporting asylum seekers to the San Diego airport as early as 3:30 a.m., Peled’s days typically start around 7:30 at the San Ysidro Port of Entry.

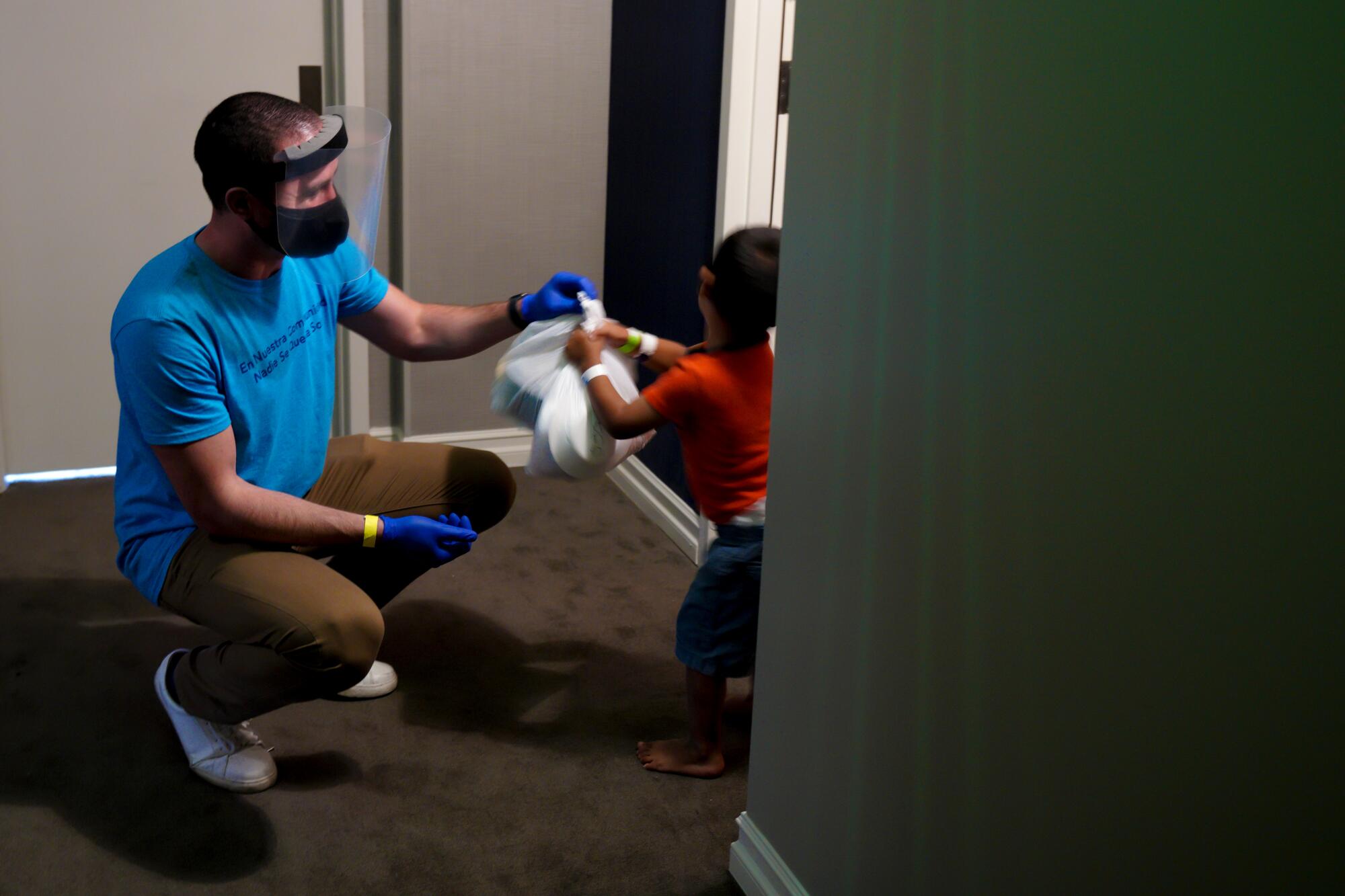

Peled, 27, usually wears what he calls his “uniform” — a T-shirt that reads, “En nuestra communidad, nadie se queda solo” (In our community, no one is left alone).

The former child migration and protection program manager for UNICEF USA hopes the message helps the asylum seekers distinguish him from law enforcement and other government officials. At the port, he and the Jewish Family Service legal team check the asylum seekers’ paperwork after they‘ve confirmed their identities with Customs and Border Protection officers.

The asylum seekers were tested for COVID-19 the day before at a staging shelter in Tijuana. At the port of entry, they are tested a second time by UC San Diego Health medical staff.

Then they file onto a Jewish Family Service bus, decorated to help asylum seekers celebrate the moment, which drops them off at one of four hotels where the nonprofit has booked rooms, and the asylum seekers quarantine there until they receive their test results.

Clark said she’s seen tears of joy streaming down asylum seekers’ faces as they walk to the bus.

“There’s a moment where they all of a sudden realize they’re not in custody anymore,” Peled added.

Last Friday, among the first that Peled helped onto the bus was a Venezuelan family of three — Meivys, Edixón and their 4-year-old daughter. They’d been waiting in Tijuana under the Remain in Mexico program for nearly two years.

Peled was also the staff member who brought lunch to their hotel that day, rolling a hotel cart down the hallway with bottles of water and bags of food that could be heated in the rooms’ microwaves.

“Hallelujah!” one woman exclaimed, laughing, when he knocked on her door to deliver the meal.

Another woman asked in Portuguese about her COVID test results. Brazilians are one of the largest groups that the shelter has received in March.

Peled answered her in Spanish, hoping that she would understand because of the similarities between the two languages. She thanked him and closed the door.

Peled sees the work that Jewish Family Service is doing as an intersection between what the asylum system is and what it could be.

“We are operating within the context of a broken immigration system and responding to the needs of vulnerable individuals who are trying to navigate it,” Peled said. “While navigating that broken system, we are advocating for and working to build a system that works better.”

The facility is the latest emergency intake site announced by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to help transition unaccompanied migrant children out of Border Patrol custody more rapidly

The asylum seekers who are released to the shelter because they chose to cross the border without permission and ended up apprehended by Border Patrol are a symptom of the broken system, he said. The process for winding down the MPP program, which doesn’t require asylum seekers to spend any time in holding cells, he added, could be a blueprint for what custody-free, humane asylum processing looks like in the future.

The shelter where Jewish Family Service served asylum seekers before the pandemic has become a staff hub to store food and supplies as well as the office where workers and volunteers call families to make travel arrangements.

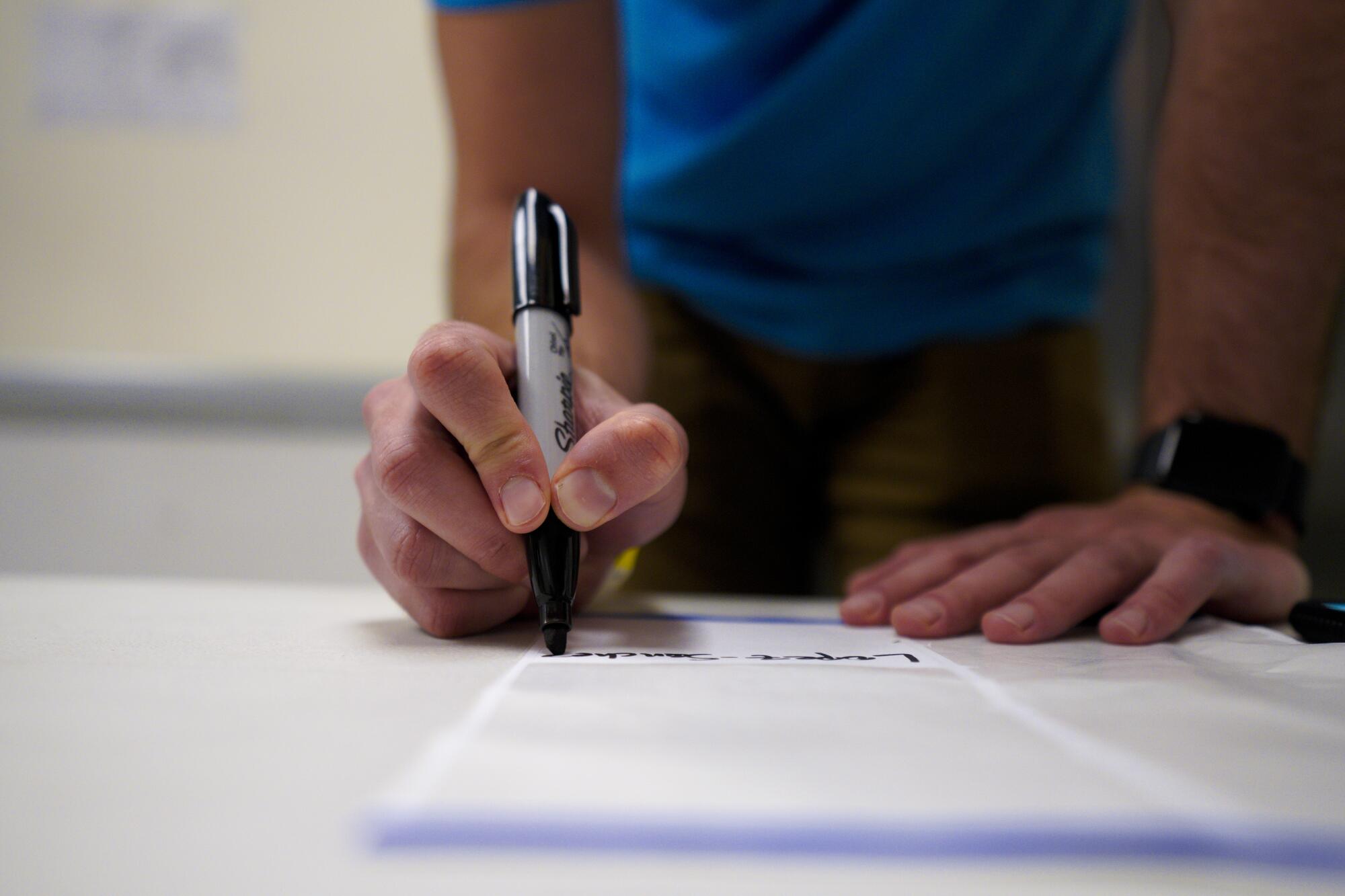

Peled met with Clark there on Friday afternoon to sort out who would pick up asylum seekers being dropped off by Border Patrol that day.

At first, the Border Patrol wouldn’t notify the shelter about releases until the migrants had already been dropped off at a bus stop, Peled said, and the staff would scramble to send someone to find them.

They’ve since built up communication with agents at the region’s stations to be able to coordinate drop-offs, Peled said. As he and Clark talked, another email from the Border Patrol came in about additional arrivals.

Peled escorted Meivys, Edixón and their daughter to the airport on Monday evening.

They and the other asylum seekers he picked up from the two hotels he stopped at with the organization’s 15-passenger van were waiting for him in the lobby when he arrived.

Once in the van, he asked in Spanish, “Who wants to DJ? What artist do you want to listen to?”

“Salsa,” a woman responded after a shy pause.

When Peled pressed her to name an artist, she selected Marc Anthony.

At the airport, he dropped off part of the group at one of the terminals to wait for him while he escorted the other half to their gate. Most were headed to Miami.

A Transportation Security Administration supervisor recognized Peled and came to see what special needs the group had for identity checks. Sometimes the asylum seekers don’t have passports, or their travel documents are expired.

Monday’s group passed through relatively smoothly — only one man had an expired passport. He received an extra screening.

It was only after crossing through security that the asylum seekers began to chat with each other, their tensions finally eased knowing that nothing more stood between them and their flights.

For a mother and daughter from Nicaragua, it was their first time on a plane.

Peled exchanged fist bumps with the group and wished them well before quickly walking back to the other terminal to help the Venezuelan family check in and get through security.

At the gate, their young daughter began snacking on the bag of food that Peled had given them for the journey while the couple recalled what they had been through.

While in Mexico, they shared an apartment with another Venezuelan woman who had been returned to Tijuana under MPP. They were so afraid of the neighborhood they lived in that they never went outside, Meivys recalled. One of their neighbors was a drug dealer who was raided by military and police.

After the landlord raised their rent, they spent the rest of their time in Tijuana bouncing from place to place, staying with whoever would take them in for a time.

“It was difficult, but thank God for putting good people in our path,” Meivys said in Spanish.

When her family received the call that it would be their turn to be processed into the United States, she felt a moment of relaxation for the first time in years. Once in the United States, that feeling deepened. The first night in the San Diego hotel, the family slept until the afternoon.

“What I say to people waiting is to have faith,” Meivys said. “The wait is hard, but it is worth it.”

Her dreams for life in the United States center on her daughter and the opportunities the girl will have here. She joked lovingly about her daughter’s Mexican accent, an effect of the girl spending half her life living there.

Before leaving the family to board the plane, Peled paused to snap his traditional selfie.

On Monday, he wrapped up work close to 11 p.m.

“Tomorrow, we do it all again,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.