Q&A: From Van Gogh to ‘Aquaman,’ Willem Dafoe likes to mix it up

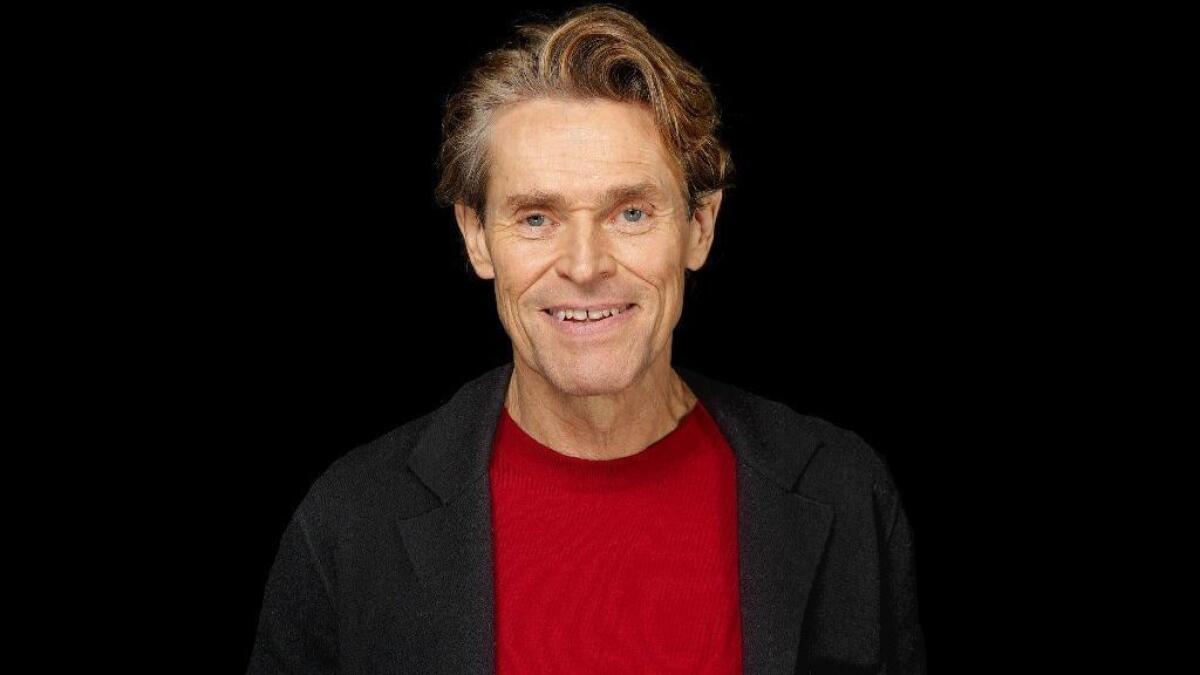

After 39 years in the industry, Willem Dafoe has probably seen it all. But when asked how he ended up playing Vincent van Gogh in his old friend Julian Schnabel’s quasi-experimental “At Eternity’s Gate,” for which he recently received his first lead actor Oscar nomination (after three previous supporting nods), Dafoe noted it was, “Not your usual industry offering.” First came informal conversations, then a request from Schnabel for Dafoe to pore over some of Van Gogh’s letters, then the painter-turned-director invited Dafoe, a founding member of the anything-goes theater ensemble the Wooster Group, to his home for his version of a screen test. “He put a lousy, cheap fake beard on me and shot some pictures just to imagine how I’d look,” says Dafoe, 63. Then came fine arts boot camp, where Schnabel taught Dafoe about the world of oil paints, brushes and easels.

When the film was released in September, critics hailed Dafoe’s immersive portrayal of the Dutch impressionist painter’s final days in the south of France as one of his finest performances since playing Jesus in Martin Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ.” Recently, Dafoe spoke with The Envelope by phone to talk about painting, awards and the grab-bag quality of his career.

There’s been a slew of other Van Gogh films and documentaries. What appealed to you about this one?

I feel like Julian really broke the back of the traditional biopic as well as the cliché of Van Gogh as this deranged, misunderstood, closed person. The truth is that in his letters and paintings, there was evidence that he wanted to connect. He was probably happiest when he was painting and alone in nature, but he did want to share his vision with people. In beating back that cliché, it attacks the bourgeois notion about what makes people happy in life. While he had lots of challenges, you can also imagine that he was a very awake, very turned-on person. He was so productive – and his paintings are evidence of that. You can feel the strength of all those paintings; that’s why they endured – not just because an art critic decided that he did something special. They really have a magic.

What was it like to shoot in Arles, Bouches-du-Rhône and Auvers-sur-Oise, places familiar to Van Gogh?

Fantastic, moving. Sometimes you could even recognize the landscapes from his work. The truth is that land management in that part of Provence is such that some of those fields and the contours haven’t changed that much. The landscape isn’t dotted with McDonald’s. It’s preserved in a way that it’s easy to imagine that you’re looking at what he was looking at. So that really becomes a connection. You can feel the presence of him in that landscape.

Share some of Schnabel’s key lessons when it came to a painter’s relationship to art.

He was a freak about how I held the brushes in my hand, how to hold multiple brushes. How I arranged my palette, how I touched the brush to the canvas. Once I started painting and organized materials, had the proper look and physical technique, then he started talking to me about ways of seeing. I’d look at a cypress tree, and I’d rush to make a good likeness. He’d say, “No, no. It’s not just deconstruction. Look at the way the light hits it. Paint what you’re seeing, not what you think it is.” I was so actively painting and looking at trees and landscapes and line and color in a different way that it was all really a swirl for me.

Vincent often rapturously communes with nature. Were those scenes scripted or improvised?

[laughs] It wasn’t like, “Willem, go clomping off into the field.” It was, “Find something beautiful that you want to paint.” “Now set up your paints.” “Now paint.” There lots of structure, but we also invented things. Julian doesn’t do a lot of [camera] coverage, and he’s very decisive, so we’d often finish very early and take the rest of the day to walk around, sometimes with cameras, sometimes not.

How did you hear about your Oscar nomination?

I’m a little embarrassed to say that I really wanted it to happen. I’m working on “Togo,” a film for Disney in Nordegg, a remote place in Alberta, Canada. So I woke up early, went to my little computer and in the darkness of my modest motel room, I found out. It was surreal. This movie was a great experience for me, and I’m so happy because [the nomination] raises its profile.

In the same year, you appeared as Van Gogh in a small drama as well as Vulko, advisor to King Orm in DC’s highest-grossing film ever, “Aquaman.” Is this all part of a grand plan or do you just love saying yes?

When you say that, that’s music to my ears. Not because I have an ambition to show off that I can do all these things but that I’m not trapped or tired, that I’m still open to the challenges specific to each movie. I’m not interested in accumulating these experiences so I can walk around with a charm bracelet of achievements. I’m interested in surprising myself and surprising people. After years of working, it’s fresh each time. I don’t always have that classic beginner’s flexibility, but that’s what I’m interested in cultivating.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.