The Hammer Museum gets together with artists, outside the box

The Hammer Museum not long ago held the final meeting of its second artist council, a group of a dozen artists from around the world who’d been brought together to address some of the museum’s more vexing logistical and philosophical problems. In the wrap-up discussion, there was near unanimous appreciation for the open dialogue between the artists and museum administrators, but there was also a healthy dose of dissent and even indignation.

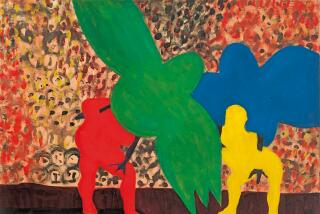

Kerry James Marshall, an artist whose work focuses on African American history and is living in Chicago, was exasperated by the council’s supposedly big idea -- turning the wayfinding and welcoming functions of visitor services over to artists -- that emerged from two weekends that the group spent together over the past year. According to Marshall, the idea “was too tame, too much of the same old thing that museums do.”

His vehemence caught the group by surprise, and Teddy Cruz, an architect who had spent the weekend arguing that the Hammer needed to become more a place where art is made than just a place where it is displayed, laid a compromise-forging hand on Marshall’s shoulder and tried to reposition the proposal in more theoretical terms. But Marshall wasn’t budging, and throughout the ensuing back-and-forth between the artists, the Hammer’s director, Ann Philbin, sat with a staggered look on her face.

Finally, she interjected, “I assure you that the notion of the Hammer turning visitor services over to artists is a scary proposal for the museum.” And then, precisely because Marshall was the kind of artist who could be counted on to challenge the status quo, Philbin turned to her staff and said, “Budget Kerry into every artist council.” The group, including Marshall, erupted in laughter.

Advice from experts

The Hammer assembled its first artist council in 2007. Funded by a grant from the James Irvine Foundation, it brought together 12 artists at different stages of their careers from different parts of the world. The artists spent three weekends together in closed-door sessions with curators and administrators. They ranged from emerging artists such as Ruben Ochoa, whose work addresses social and architectural issues in urban Los Angeles, to veteran visual artists Barbara Kruger and Lari Pittman. “Nobody thinks outside the box better than artists do,” said Philbin. “So that’s where we’ve gone for new ideas.”

On the logistical side, the Hammer wanted advice on how to deal with standard museum practices like interpretation of artworks and outreach to the community; on the philosophical side, they wanted to know how artists and institutions like the Hammer could be part of a larger cultural conversation.

Though many museums have artists on their boards of directors and other committees, the Hammer, when researching the premise of the artist council, found no other museum that was engaging artists in quite this way. Photographer Catherine Opie, who was on that first artist council and who has served on the Hammer’s board of overseers, recalled, “A lot of times, an institution forgets they can have a discourse with an artist beyond showing their work hung on a wall.”

Although it is a medium-sized museum with contemporary and historical programs and collections, the Hammer is in many respects akin to spaces like LACE in Hollywood and Artists Space in New York that were founded in the 1970s as alternatives to big, institutional museums, which were more focused on objects than on artists and new art forms, such as video and performance art. Philbin, like many of the curators who have served under her watch, began her career in this environment. “All of us came from the alterative space movement,” she recalled. “The whole notion of alternate spaces was to be artist-centric, and that has been the touchstone for me at the Hammer.”

Nonetheless, the conversation started slowly. Narrowly focused topics presented less than scintillating avenues for discussion. For example, how should the museum handle its didactic wall texts? (The artists wanted to eliminate them; the museum argued to keep them.) However, the conversation soon branched out in unexpected directions, with an unanticipated ferocity.

Opie, who teaches in UCLA’s MFA program, urged the Hammer to provide access to public programs beyond the walls of the museum. “The Hammer has unbelievably rich programming,” recalled Opie, but it was accessible only to people who could visit the museum regularly. Making the programming available on demand to a virtual audience was unanimously endorsed by the other artists, particularly those such as Shahzia Sikander, Doris Salcedo and Dinh Q. Lê, who had lived in Lahore, Pakistan; Bogotá, Colombia; and Vietnam, respectively.

The idea of a better website wasn’t new to the Hammer, but it also wasn’t on top of its long list of funding priorities. “It was maybe No. 10 on our list,” recalled Philbin. “But the artists said, ‘You need a new website now.’ ” So the Hammer obliged.

The sophisticated new site launched in November and includes audio and video of, by and about artists; it also includes audio and video recordings of Hammer public programs, images from current and past exhibitions, and the permanent collection. There are blogs and news items and postings of artworks-in-progress by some of the Hammer’s artists-in-residence. In short, a visitor can have a fairly complete experience of the Hammer without going to Westwood.

With the redesigned website, the Hammer has experienced a 30% jump in Web traffic in the last four months, and more than 15,000 visitors have downloaded their podcasts. They expect 800,000 visitors to the site in the coming year, and they’ve tracked hundreds of hits coming from surprising places like Iran and Egypt. “This expands our audience enormously,” said Philbin, who expects a related jump in physical attendance. “It takes us from being a local institution to being an international venue.”

But the artists wanted more. Mark Bradford, an L.A.-based artist who creates large-scale works from the layers of advertising posters that build up on urban walls, advocated that the Hammer do some programs outside its building. “It’s healthy for cultural institutions to try to build relationships with other parts of the city,” said Bradford. “L.A. is so spread out, and for all of its plurality, the real estate can be zoned off. People say ‘the Westside,’ ” where the Hammer is located, and “there are strong cultural assumptions.”

As a result, the Hammer hosted a handful of off-site events, such as Belgian filmmaker Johan Grimonprez’s work-in-progress screenings at the Mandrake, a Culver City bar, and at Machine Projects in Echo Park. Edgar Arcenaux, another artist-in-residence, is undertaking a community-engagement project in the Watts Towers neighborhood, which will be the Hammer’s first off-site installation.

C’mon, loosen up

By the time the Hammer convened its second artist council last summer, administrators had a different set of questions and a looser format for discussion. This second council included Jim Hodges, Tim Lee, Rodney McMillian, Aleksandra Mir, Hirsch Perlman, Alexis Smith, Frances Stark and Grimonprez. This time, the Hammer wanted the artists to address what it perceived as an architectural liability: the long, underpopulated hike from the parking garage, through the cavernous lobby, stairwells and corridors to the Billy Wilder Theater and the third-floor galleries.

The artists came up with their own agenda, which emphasized the Hammer’s need to look more closely at nontraditional art practices, such as social and public practice art that they felt were gaining greater currency. Public practice art, said feminist artist and council member Andrea Bowers, is about “working in communities and having a conversation” with the community stakeholders.

The resulting art frequently involves an event or performance or collective project that is not easily ideally suited to presentation in a museum. Mark Allen, the founder of Machine Project who was also on the second artist council, explained, “Either museums do something that lasts two hours in their theater or that lasts three months in their gallery. Contemporary art practice is much more diverse in places and forms and durations than a museum is set up for.”

By considering the fairly prosaic problem of directing visitors to bathrooms and galleries and discussing the problem of engaging art forms that are at odds with what normally happens in a museum, the group found a way to conflate the seemingly unrelated problems. The artists bundled them together in something they dubbed the Help Desk. The Help Desk would be a curated art program that would take the massive, vacant desk in the Hammer’s largely empty lobby and put it to use by inviting artists to do projects that would deliver the greeting and informing functions of visitor services.

If the Hammer could pull this off, it could introduce a performance element into the daily life of the institution while also allowing visitors to have a direct experience, not just with art but also with artists. And the idea would provide the Hammer with something the museum adores: a counterintuitive human solution to a problem that many museums were solving in an increasingly technological fashion.

When the final session adjourned, Philbin was exhilarated, declaring that the artist council would become a regular part of the way the Hammer does business. She also had in hand an artist-proposed solution to a chronic problem, which she would immediately try to implement. The idea still scared her, and the parameters would have to be defined, but she was already moving to make it happen. “Artists come up with ideas that make us uncomfortable,” said Philbin. But that seemed to be exactly what she liked best about the proposal.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.