After a casino boom, a Mississippi county deals with a reversal of fortune

Growing up in Tunica at the height of its casino boom, Roosevelt Hall felt his community had been dealt a winning hand.

Lavish monuments to gaming — a gleaming high-rise tower, an Irish medieval castle, an art deco movie house — rose up amid the cotton and rice fields, flooding the impoverished Mississippi Delta county with tourists, money and jobs.

But the 38-year-old bartender is increasingly hedging his bets on the future.

Nearly five years ago, Hall lost his job when the county’s largest gambling complex, Harrah’s, closed due to a glut in the market. After securing another position at the Tunica Roadhouse, he has watched his tips dwindle from about $150 to $25 a night. At the end of the month, the casino will shut down and Hall is unsure whether he will find a secure job at one of the seven surviving casinos.

In its heyday, Tunica was one of the nation’s biggest gambling meccas, ranking third after Las Vegas and Atlantic City. But casino revenue here has plummeted in the last decade as major casino markets have exploded in dozens of cities from Chicago to New Orleans. Tunica casinos now employ about 4,000 workers, less than a third than they did at their peak.

“I’m so tired of being laid off,” Hall said one day last week as he picked up a pack of Newport cigarettes from a gas station on Casino Strip Resort Boulevard. “If I get another job at another casino, will it stay open or will it close?”

Many in this predominantly African American county of just 10,000 residents, about 30 miles southwest of Memphis, worry they are moving backward. Before glitzy casino palaces were built along the Mississippi River in the early 1990s — state legislators hoping to revive the ailing economy passed a law in 1990 that allowed dockside casino gambling in counties along the Mississippi River and the Gulf Coast — Tunica was the most impoverished county in the nation. More than half its residents live below the poverty line.

In 1985, the Rev. Jesse Jackson dubbed the county “America’s Ethiopia” after touring Sugar Ditch Alley, a block of downtown Tunica, the county seat, where residents dumped raw sewage into a ditch that flowed alongside their run-down wooden shacks.

Today, about 29% of the county’s residents live in poverty — significantly less than a quarter of a century ago, yet still nearly two and a half times the national average.

And across Tunica, there are signs of decline.

Inside the Roadhouse, a Western saloon-themed casino improbably positioned within a faux Bavarian castle with a moat, the blackjack and poker tables are dim and without dealers. Most nights the kitchen behind the bar is closed. Amid a whir of giddy beeps and chimes, just a smattering of players tap buttons and pull levers on penny slots and video poker machines.

“There’s no future in casinos,” Dondrell McKay, a 30-year-old security guard, said as he stood at a Roadhouse entrance, monitoring an empty hallway. He shrugged when asked what he would do next. “I’m done with casinos.”

A few miles east, weeds sprout across the sprawling 2,200-acre Harrah’s complex that once housed a massive casino, convention center, three hotels, an 18-hole golf course and an RV park. Along the four-lane highway next to the abandoned complex, a Valero gas station and Sonic Drive-In also are shuttered. An outlet mall that once housed national chains, from Nautica to Old Navy, now offers a flea market, a pawn shop and a string of discount stores with penny-pinching names such as “Super Bargain” and “Cheap Charlie’s.”

With a steep drop in tax revenue from North Mississippi casinos — from about $1.66 billion at its peak in 2006 to $885 million in 2017 — the county administrator is slashing budgets, no longer refilling positions when employees leave and cutting “non-essential” services at local blues and history museums and the county’s 6,000-seat Arena and Expo Center. Firefighters worry county officials may switch to a volunteer fire system or cut the number of full-time firefighters by half.

“This county is tumbling slowly,” said Kevin Drake, 32, a firefighter with the North Tunica County Fire Department. He huddled in the fire station’s TV room last week as officials held a meeting about the future of the department. After two hours behind closed doors, no decision was reached.

At the Hollywood Café, a local blues club that used to pack in tourists and locals with catfish, hush puppies and fried dill pickles, servers are feeling the pinch. On a good weekend, Keisha Jackson, 36, used to make roughly $600 in tips. Now she’s lucky to take in $100.

Still, most everyone agrees there are still more opportunities than before the casinos came, when there were no paved roads, limited water and sewage lines, and few jobs outside agriculture.

“The gaming industry brought Tunica into the 21st century,” said James Dunn, president of the Tunica County Board of Supervisors.

Even with the decline, the region’s boosters exude optimism, saying new roads and infrastructure, and its proximity to Memphis, make the county well-positioned for growth. Plans are already in the works, they say, to build a water park on the site of the former Harrah’s Casino, a $90-million mixed-use development in the eastern part of the county, and one of the first large wind farms in the Deep South.

“I see Tunica as a beacon for the rest of the Delta,” said Charles Finkley Jr., president of the Tunica County Chamber of Commerce and Economic Development Foundation, noting that the county is better off than neighboring Quitman County, which has no gaming and still has 40% of residents living in poverty.

While there are some signs that the economy has diversified — in the last decade, a pair of German companies have opened new plants manufacturing stainless steel pipes and crankshafts, creating more than 300 jobs — residents worry that more casinos may go out of business as the market becomes more competitive.

In November, voters in neighboring Arkansas passed a constitutional amendment authorizing four casinos, including one 35 miles from Tunica in West Memphis. Meanwhile, officials in Memphis are discussing legalizing sports betting on Beale Street.

Many workers here are tired of job conditions and insecurity, said Marilyn Young, who leads the Tunica County Workforce Development Center. Most shifts run from the late afternoon to the early hours of the morning — a tough gig for parents, particularly those without cars or an adequate salary to pay for baby sitting. Young hopes to work with casinos and county officials to set up a 24-hour daycare and transport system that can span the rural area to ferry workers without cars.

“The casinos have a lot of resources,” she said. “I think they could give back a bit more.”

While neat subdivisions of brick homes and condo complexes now dot the flat rural county of cotton fields, some areas show little sign of progress. In Old Sub, an African American neighborhood north of the city of Tunica, wooden shacks strain under the weight of sagging roofs, and ramshackle trailers are patched with strips of corrugated metal. Faded plywood covers the windows of empty clapboard homes.

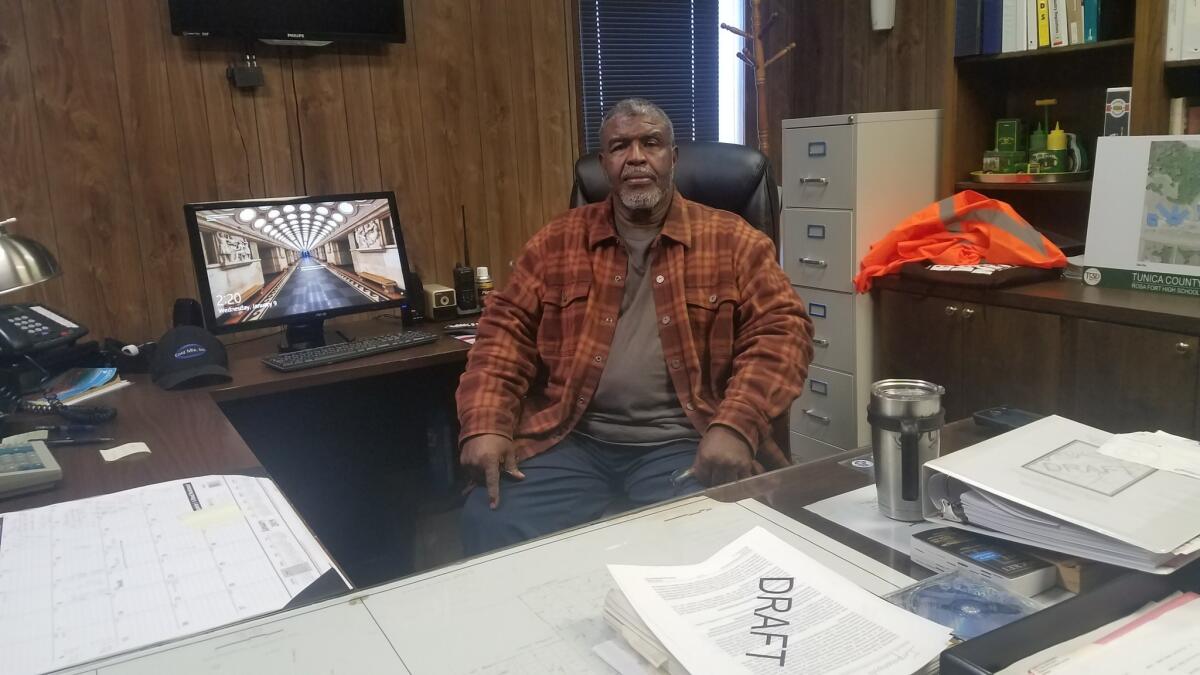

“So many lost chances of really making a change,” Joe Eddie Hawkins, 65, a longtime community activist who now works as the county road manager, said last week as he drove along Anderson Street, past the empty lot where he was raised by his grandmother.

He sighed.

“Would you think a county that got almost a billion dollars from the casinos, a county of just 10,000 people, would look like this?”

Some blame former government officials — who until recently were predominantly white — for wasting hundreds of millions in casino revenue, cutting property taxes and building airports, sports arenas and gymnasiums rather than investing in low-income housing and job training.

Still, Hawkins does not place all the blame on former leaders. Everyone enjoyed the tax breaks, he said, and residents should have done more to pressure officials to channel the money toward needy residents.

On the outskirts of Tunica, where some residents of Sugar Ditch Alley were relocated to mobile homes in the 1980s, Larry James said casinos had transformed the county, offering many residents a path out of the old Southern agrarian way of life.

But the 62-year-old retiree, who worked as a restaurant manager and chef for a string of casinos for nearly two decades, said his dirt-poor neighborhood had little to show for all the casino money.

“They built a few million-dollar buildings, a lot of things that weren’t necessary,” he said as he scanned his block of battered, rusty trailers on gravel and mud. “An aquatic center? A practice soccer field? They could have reconstructed this entire neighborhood.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.