Prosecution of false accuser in rape case seen as difficult

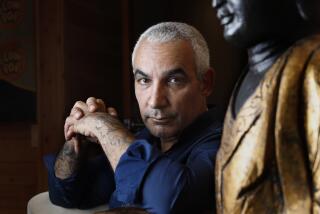

A day after a former high school football star had his rape conviction dismissed, attention focused on the woman who recanted the sexual assault claim she made 10 years ago.

Wanetta Gibson was a high school sophomore when she accused Brian Banks of raping her at Long Beach Poly High School. She and her family sued the school, receiving a $750,000 settlement, and Banks spent five years in prison after pleading no contest to forcible rape.

Even though a judge tossed out the rape charge Thursday, it remains far from certain whether Gibson, 24, will face any consequences.

Banks, now 26, said he wants to put the ordeal behind him.

“We do not plan on taking any legal action against Gibson,” said Banks’ attorney, Justin Brooks of the California Innocence Project. “We do plan on filing a state claim for the $100 a day Brian is entitled to under state law 4900 for every day he was wrongfully incarcerated.”

L.A. County prosecutors have said a case against Gibson for making false accusations would be tough to prove.

Legal experts said it could also be difficult for the Long Beach Unified School District and its insurer to get the settlement money back.

Then there is the reality of Gibson’s life.

Court records suggest she has few assets: She received public assistance for a time and her children, ages 4 and 5, still do, according to two suits brought by the county in an attempt to collect child support.

Gibson, who could not be reached for comment, was ordered initially to pay $600 a month toward their support. But in the last year, county officials said she didn’t have to pay anything, citing a lack of income and employment.

According to Banks and his private investigator, Gibson refused to tell prosecutors that she had lied, so she wouldn’t have to return the money she and her family had won in court.

She also said she feared it would affect her relationship with her children, Banks’ attorney said in court papers.

The statute of limitations for making a false claim is four years, but experts say it could restart when a previously hidden crime is discovered. In this case, Gibson testified in 2003 during Banks’ preliminary hearing, but recanted her accusation last year. “No, he did not rape me,” she told Banks and his private investigator in a recorded conversation.

“The prosecution can say that we only learned last year that the crime of perjury occurred and therefore we are still within the statute of limitations,” Loyola Law School professor Stan Goldman said.

The fact that Gibson was a juvenile when she initially made her accusation poses a potential complication, as does the fact that she has since recanted her recantation. But Goldman said the large monetary settlement she received might make charging her a priority for prosecutors trying to ensure the integrity of the criminal justice system.

There is no official investigation by Long Beach police into Gibson’s conduct, but officers are “reviewing the matter” and “will be in consultation with the district attorney’s office following the review,” said Lisa Massacani, a department spokeswoman.

As for the money Gibson and her family received, the school district declined to comment. The attorney who represented the district in the civil negotiations said the confidential settlement paid Gibson $750,000 and not the $1.5 million cited in Banks’ court filings. Attorney Allen L. Thomas said that during the three-year case, he doubted Banks’ guilt on many occasions.

“When I took his deposition in prison, I felt like I was facing an innocent man,” Thomas said.

Ultimately, the decision to settle lay with the district’s insurance company, he said. Thomas said that the district had not asked him to revisit the case in light of Banks’ exoneration, but that he was personally troubled and believed “someone should look at it. Did she perpetuate a fraud on the government?”

Gibson had reached out to Banks on Facebook last year because she felt guilty that he wasn’t able to go to college and play football, and she had “a desire to make amends,” Banks’ attorneys said in court documents.

When Banks heard from her, he recalled, “I stopped what I was doing and got down on my knees and prayed to God to help me play my cards right.”

She agreed to meet him and a private investigator. Their conversation was taped, and her admission provided enough evidence for the California Innocence Project to take his case — and for the judge to dismiss the conviction Thursday.

“It’s been a struggle; it’s been a nightmare,” said Banks, who’s now focusing on his NFL dreams. “It’s more than I can describe, the things that I’ve been through.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.