Probes may open books at CalPERS

California taxpayers are on the hook when the state’s giant public pension system -- lately plagued by corruption scandals and huge losses -- makes a bad investment. Yet they are permitted to see little of what goes into its investment decisions.

Officials at the California Public Employees’ Retirement System have shrouded many of their multimillion-dollar transactions in secrecy, refusing to release analyses of potential investments, meeting materials and correspondence relating to venture capital, real estate and other private equity holdings.

Citing privacy laws, they have said the pension fund need not share “any documents that reflect investment recommendations and the process by which investment strategy is decided.”

But now, as some current and former officials are being investigated by state and federal authorities in probes of alleged influence-peddling and bribery, CalPERS has hired at least one outside firm to examine whether pension dollars were doled out improperly in deals negotiated out of public view.

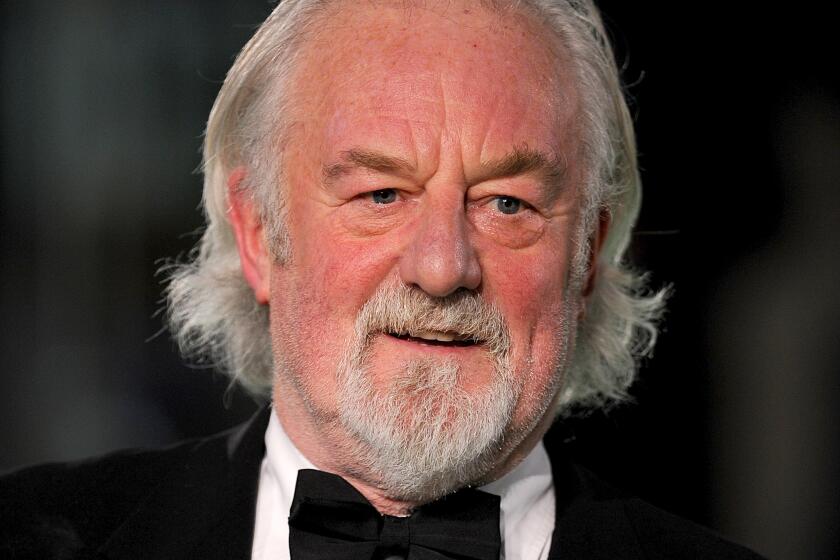

“The public has a right to know if these assets are being managed right,” said Donald Trone, chief executive of Strategic Ethos, a firm that advises pension systems on management issues. “If they are not, it is taxpayers who suffer.”

Investment losses at CalPERS, stemming from general market declines but also from real estate and venture capital deals that flopped, resulted in a $601-million increase in the amount that state taxpayers put into the pension system this year.

Although California has always been expected to contribute some cash from the state budget, the total taxpayer contribution in the current fiscal year is nearly $3.9 billion, up from about $156.7 million in 2000.

The Times, seeking documents related to politically connected deal brokers who have surfaced as targets or tangentially in corruption probes launched in New York, California and Washington, D.C., sued CalPERS for these and other public records in Sacramento Superior Court last month.

More than four years ago, The Times requested CalPERS documents related to Alfred Villalobos, a middleman accused of defrauding the pension system of more than $40 million. Villalobos, a former CalPERS board member and former deputy mayor of Los Angeles, has denied the charges.

“CalPERS cannot justify the release of information that could negatively affect the return of CalPERS’ current investment,” said officials’ written response to The Times in 2006. “Release of some of the requested information may harm CalPERS’ ability to continue to invest with top-tier private equity funds.”

In May, California Atty. Gen. Jerry Brown filed a civil complaint in Los Angeles County Superior Court accusing Villalobos of employing fraudulent business practices, including falsely representing that he and his firm, Arvco Capital Research, had securities licenses. The complaint also alleges that Villalobos used “gifts and gratuities” to cultivate “improper relationships” with key officials at CalPERS.

“Villalobos spent tens of thousands of dollars to lavishly entertain key senior executives at CalPERS, who then influenced the board to authorize investments that generated over $40 million in commissions to Villalobos,” Brown said in a statement.

The gifts allegedly included a condominium, luxury trips around the world and lucrative employment in Villalobos’ firm. At a news conference, Brown, who is running for governor, said CalPERS should have applied “clearer standards of accountability and disclosure” to the lobbying that went on behind closed doors.

CalPERS spokesman Brad Pacheco insists that the system is “more transparent than any other public pension fund in the country.”

He cites its willingness to share agenda items, minutes of public meetings and other routine documents, even as it withholds more revealing documents that other pension funds routinely share with the public.

Pacheco says CalPERS reports the rate of return on each of its private equity investments and the management fees it pays -- information it kept secret until it was sued by journalists and open-records advocates in 2003 and 2004. It has also started to report payments collected by those who lobby the fund for investment business.

But the system has kept secret records relating to Wetherly Capital, a financial firm that returned $1 million to the New York pension fund after a former employee involved in a kickback scheme pleaded guilty to securities fraud in that state.

CalPERS has also refused to release records related to the firm of Sacramento lobbyist Darius Anderson, which paid $500,000 as part of a settlement with New York prosecutors who were investigating “pay to play” practices.

And nearly all the contents of an e-mail in which a CalPERS senior staffer expressed doubts about investing in the firm Markstone Capital were removed when the pension system turned it over to the media in 2006. Markstone’s chief executive, Elliott Broidy, recently pleaded guilty in New York to paying $1 million in bribes.

CalPERS made the full e-mail public after another government agency released it to reporters intact.

In another case, the fund refused to provide documents that could help explain its sudden divestment of $24 million from a fledgling venture capital firm. CalPERS declined to explain why it withdrew the money.

Pension officials in other states, who also withdrew their funds, said they were unhappy about requests from the venture capital firm’s partners for donations to politicians on the CalPERS board.

And last week, the California First Amendment Coalition sued CalPERS for information about a 2006 real estate deal that lost $100 million.

A tenants’ group had been denied multiple requests for records about the failed investment.

The law that CalPERS officials typically cite in withholding information was passed by the Legislature in 2005 at the fund’s urging. But the law’s author, Sen. Joe Simitian (D-Palo Alto), said SB 439 is meant to keep under wraps only legitimate trade secrets and confidential financial data.

“It is not designed, nor should it be used, to withhold anything beyond [a] narrow range of information,” he said.

Pension officials say the information they are concealing fits those categories. Their commitment to openness, they say, is reflected in the system’s hiring of the law firm Steptoe & Johnson to conduct a top-to-bottom review of CalPERS business practices.

What exactly CalPERS has ordered the firm to do and how much it is paying for those services are unclear. CalPERS is keeping its contract with Steptoe & Johnson secret.

Times staff writer Marc Lifsher contributed to this report.