Op-Ed: Ferguson: No peace without representation

Before the media and the public shift their attention to the next pressing issue, we should use this opportunity to think about reforms that could prevent future Fergusons. One solution is easy to legislate and remarkably effective: increase representation.

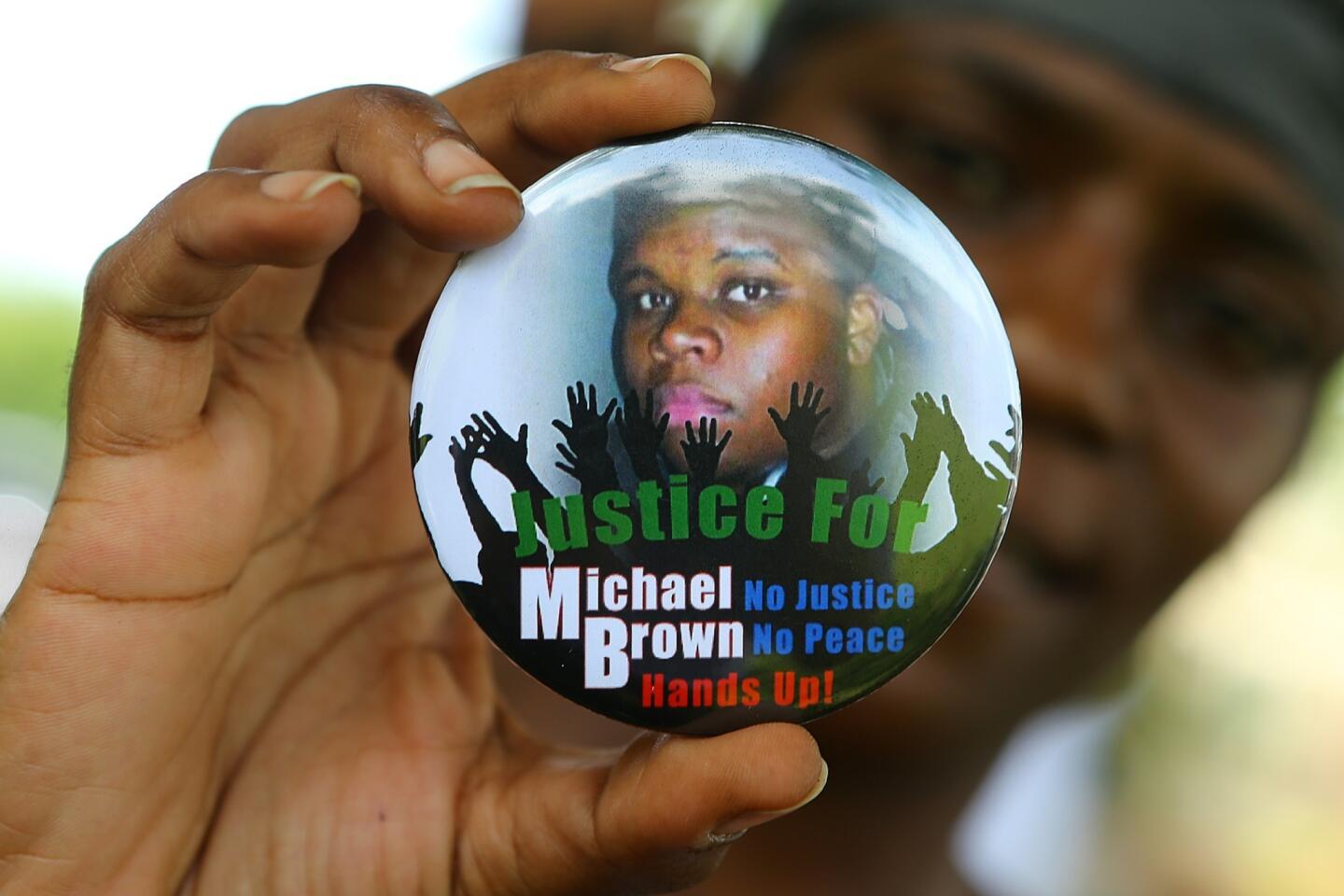

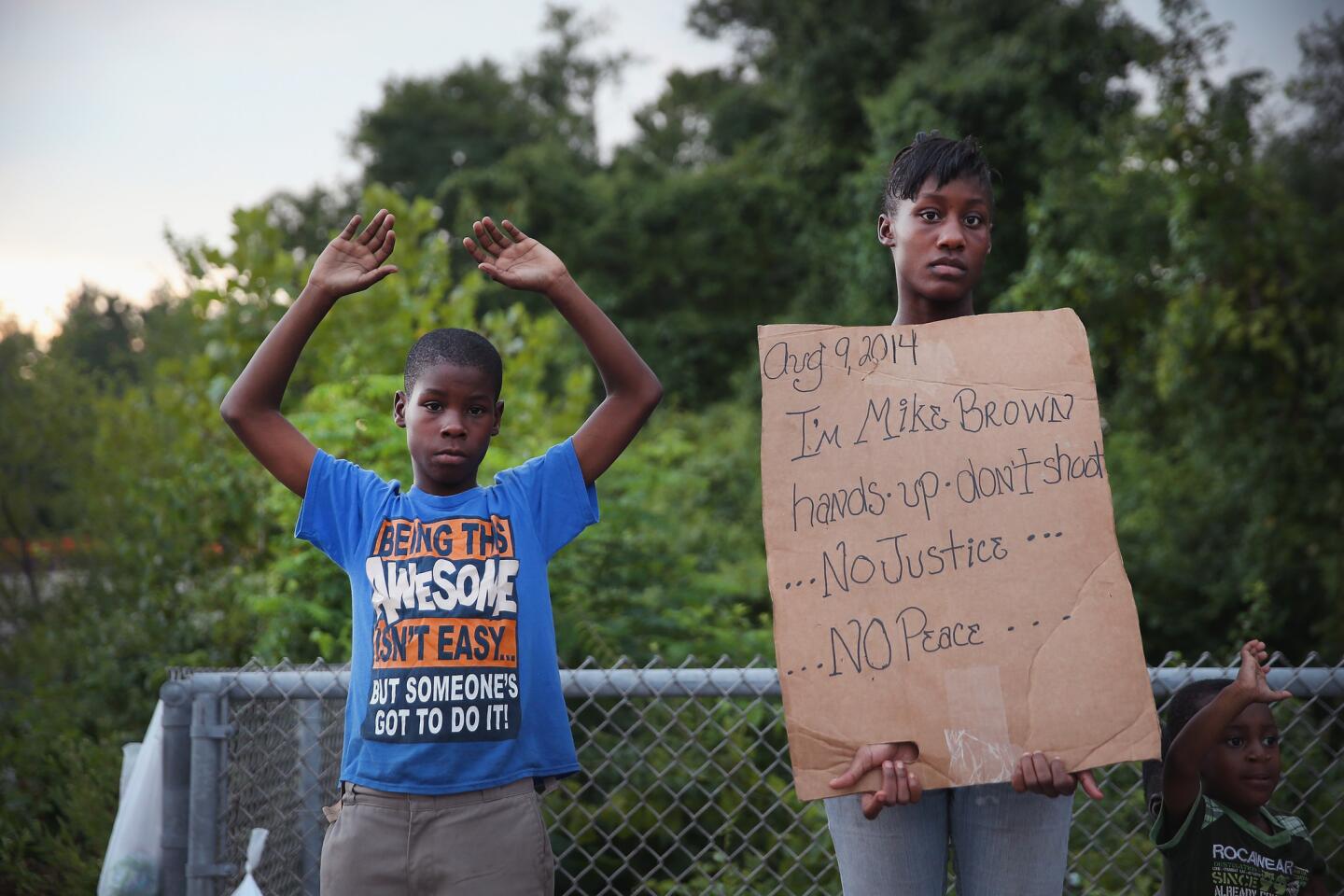

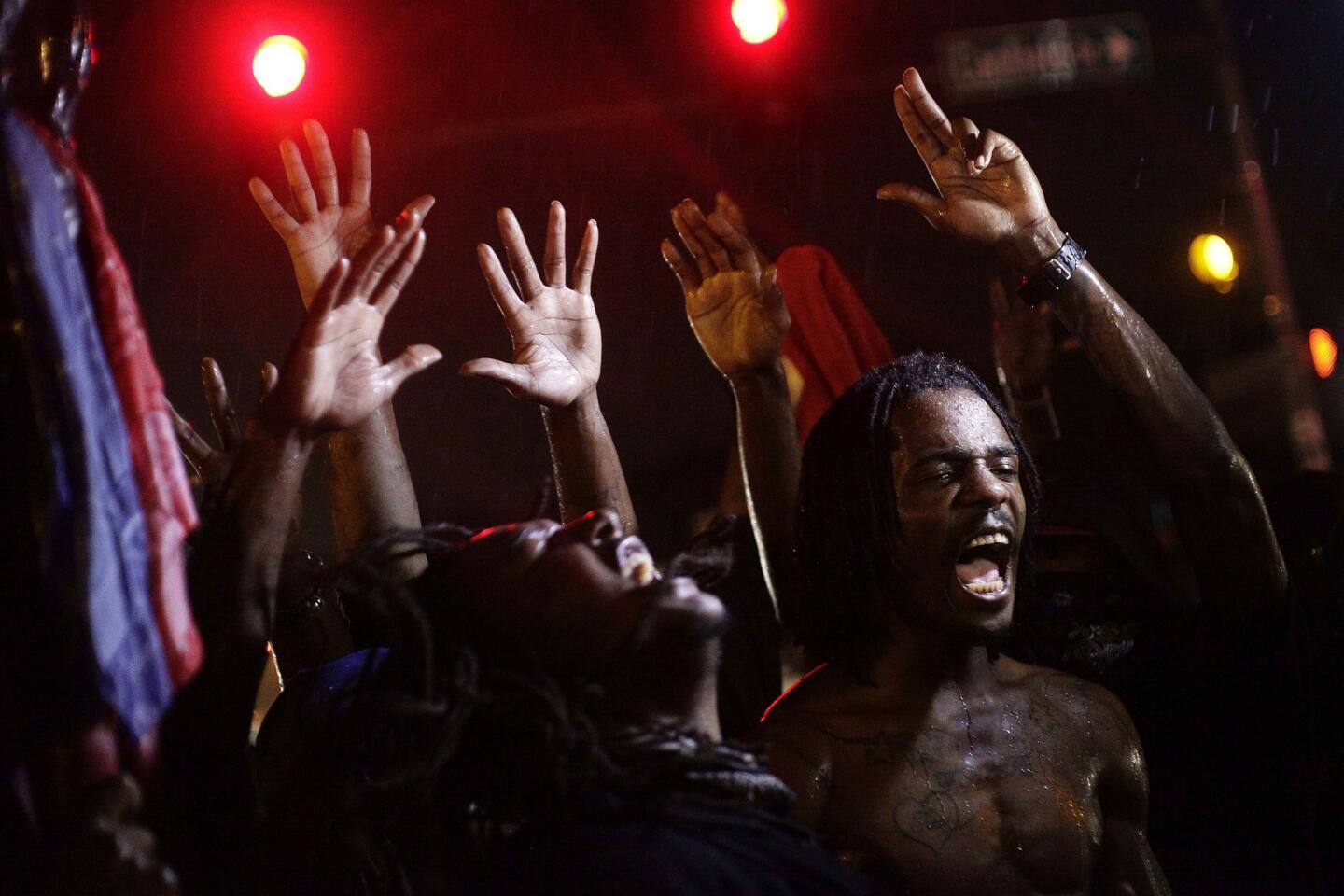

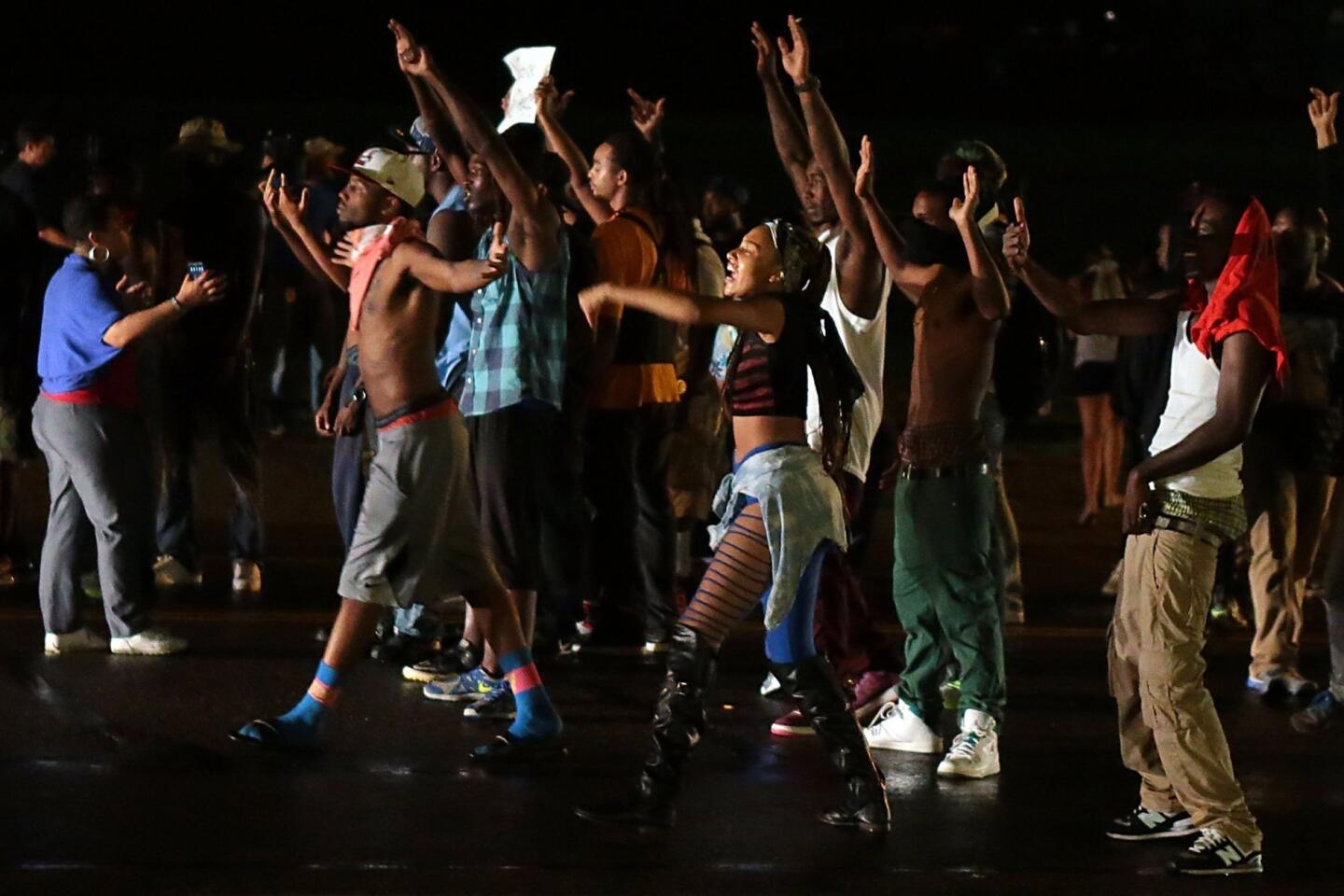

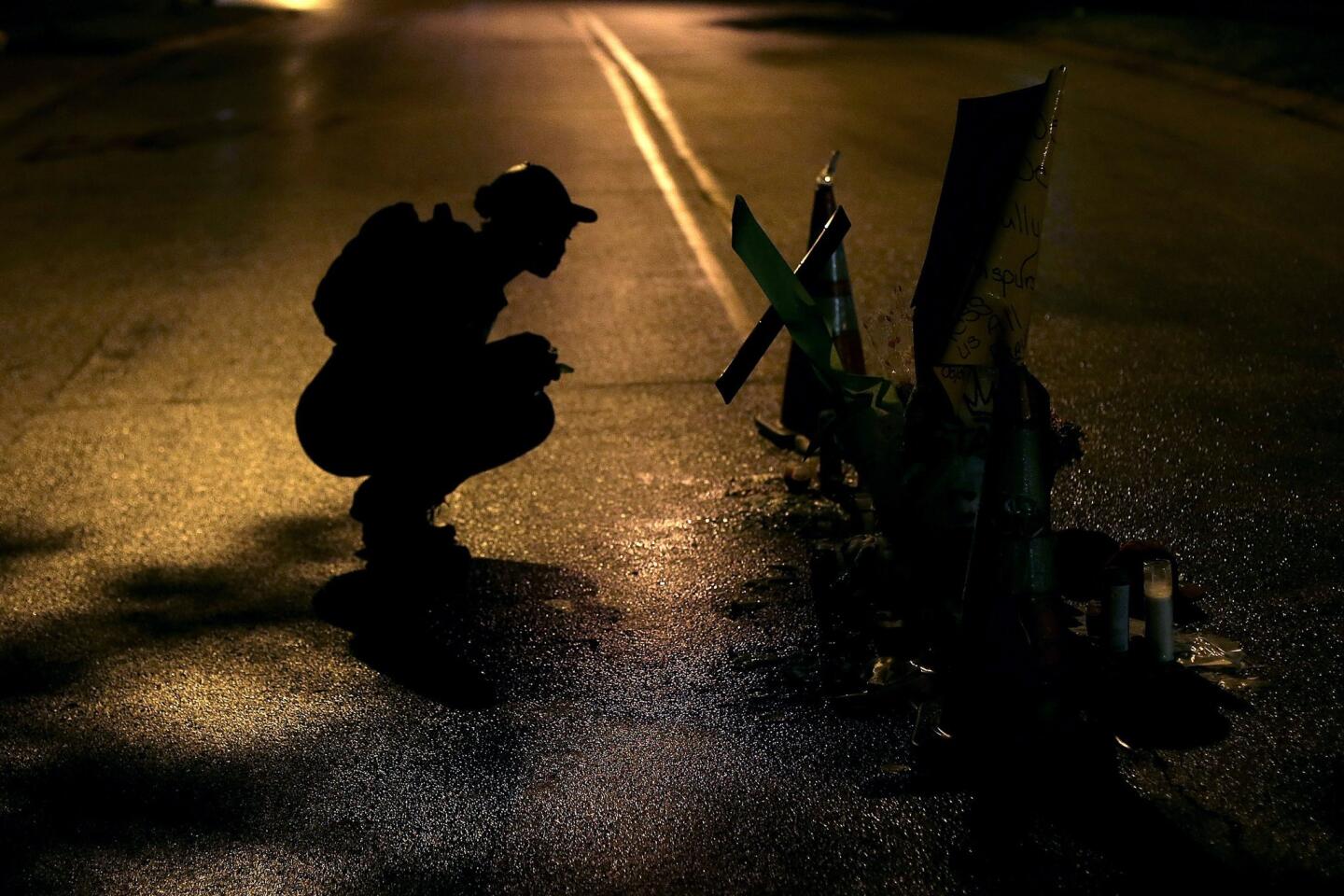

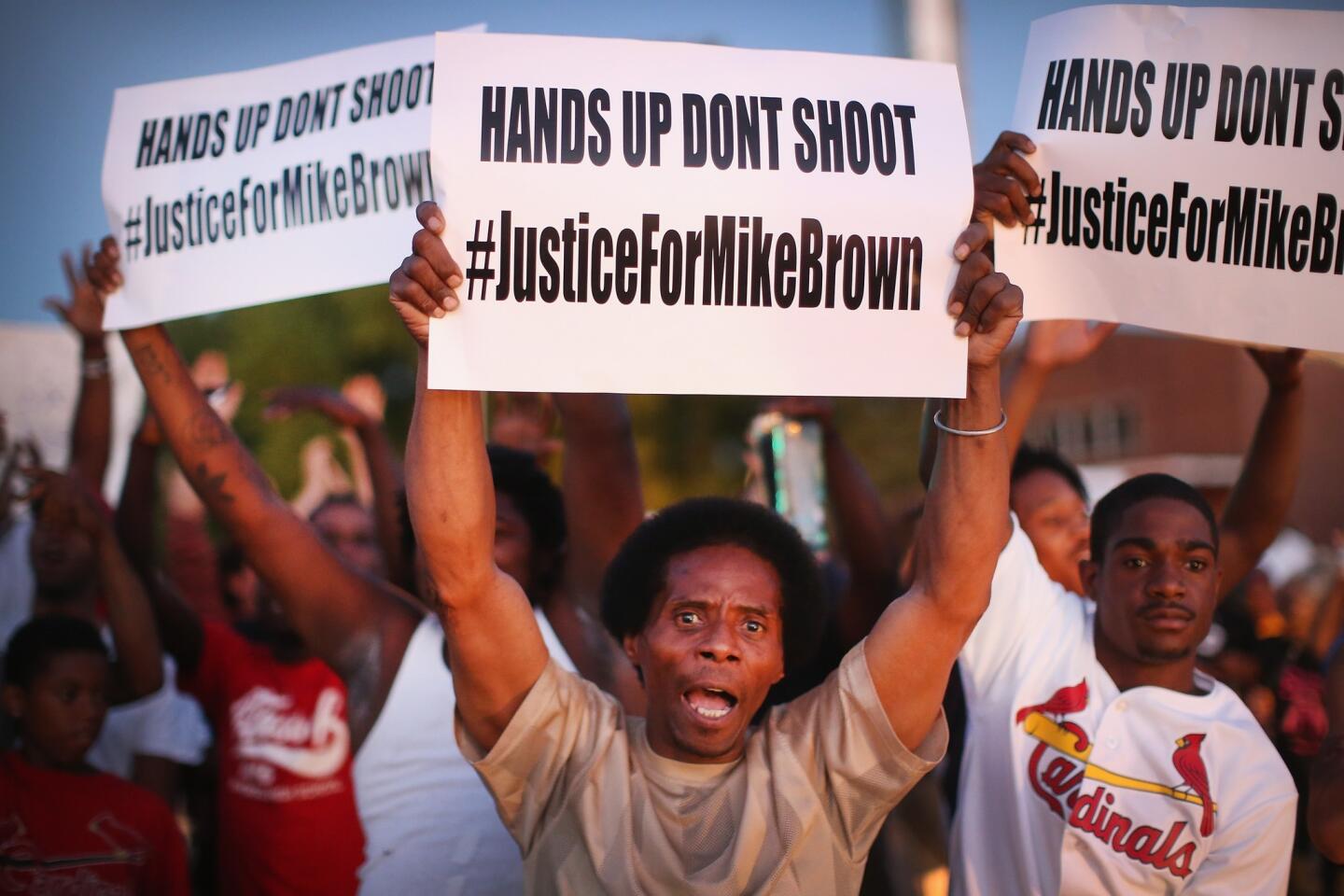

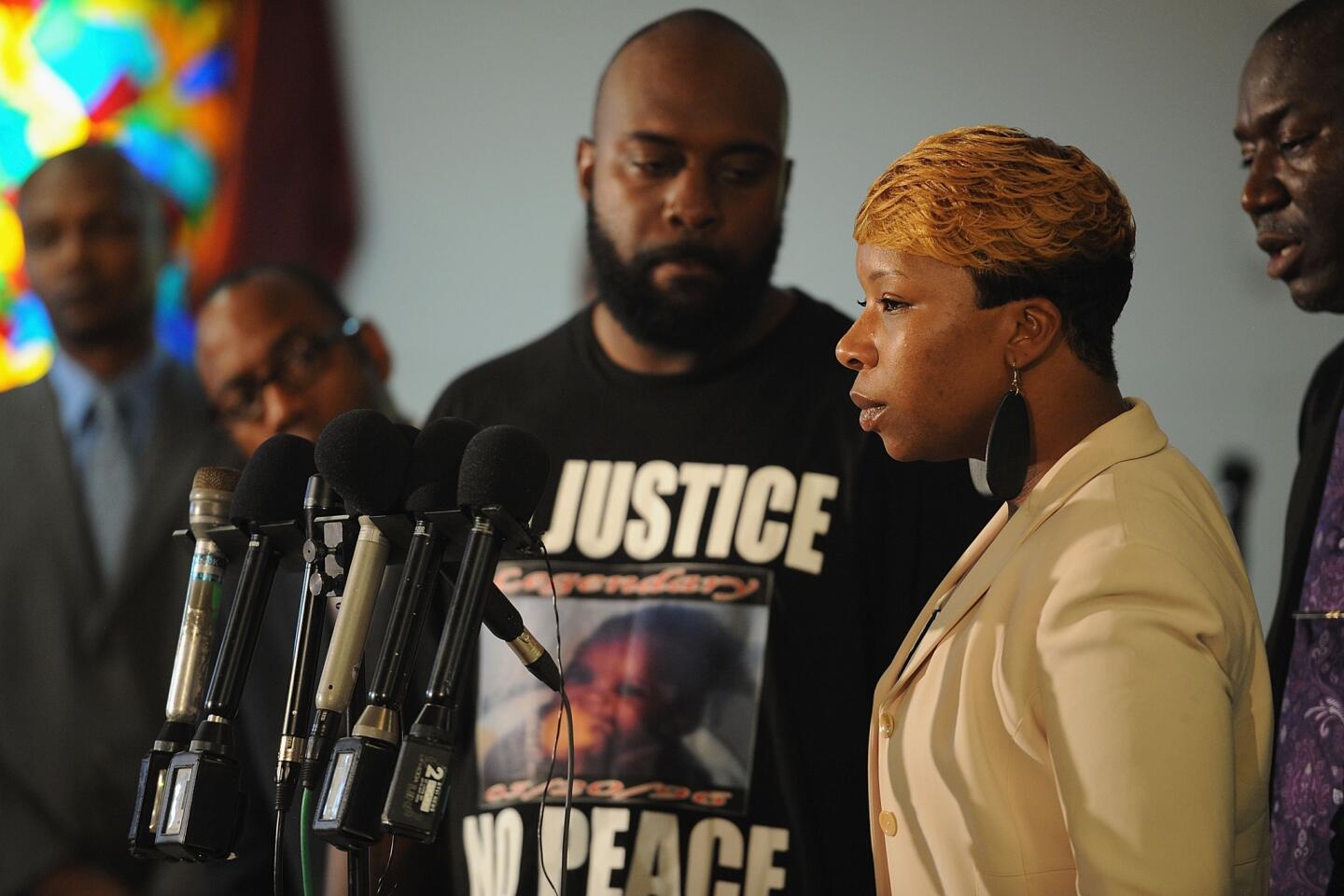

There are many factors driving the anger in Ferguson. But the fact that African Americans had almost no representation in city government shaped much of what happened in that Missouri suburb after the shooting death of black teenager Michael Brown by a white police officer. The figures are stark. Blacks represent two-thirds of the city population, yet the mayor, five of six City Council members, six of seven school board members and 50 of 53 police officers are not black.

Ferguson is not alone on this front. Across the nation, racial and ethnic minorities are grossly underrepresented in city government. African Americans make up roughly 12% of the national population but only 4.3% of city councils and 2% of mayors. The figures for Latinos and Asian Americans are even worse.

By simply changing local electoral laws, we could radically alter who votes, who wins office and the types of policies that local governments pursue. My research shows that altering the timing of local elections, shifting from nonpartisan to partisan contests, changing from staggered to consolidated council elections and switching from at-large to district elections all have important effects on local politics.

Moving from stand-alone local elections — the system that is in place in Ferguson — to on-cycle elections that occur on the same date as statewide and national contests has the most potential to increase the number of voters. Across the nation, turnout in cities with on-cycle elections is, all else being equal, almost double that of turnout in cities with off-cycle elections.

What makes timing especially appealing as a policy lever is that there are strong incentives — in addition to increasing participation and minority representation — to switch to on-cycle elections. The primary motivation for this move usually has been cost savings. In most states, municipalities pay the entire administrative costs of stand-alone elections but only a fraction of the costs of on-cycle elections. The city of Concord, Calif., for example, estimated that the cost of running a stand-alone election would be $58,000, while an on-cycle one would be only $25,000.

But other small steps toward more inclusive local elections could have big impacts as well. By adding partisan labels to local electoral ballots, we can make it easier for voters to know what each candidate stands for. By having all council seats up for election at the same time rather than staggering them across two contests, we can make each election more meaningful by having more offices up for grabs. And by electing each council member by district or ward instead of by a citywide at-large vote, we can give minorities a real chance to elect a candidate of their own.

With a few easy steps, we could move from local elections with a tiny and generally unrepresentative electorate to elections with broad and significantly more representative participation. Given that the majority of cities have electoral institutions that tend to generate low turnout, the potential to expand participation is enormous.

All of this has critical ripple effects for minority representation in office. Higher-turnout cities elect city officials who are much more representative. My analysis shows that increasing turnout could eliminate up to a third of the underrepresentation of minorities on city councils and in mayor’s offices.

Cities with higher turnout and greater minority representation tend to enact policies that are more in line with racial and ethnic minority preferences. In particular, higher turnout is associated with greater social welfare spending and greater hiring of minorities in city government.

Coming back full circle to Ferguson, my research with Jessica Trounstine of UC Merced shows that these kinds of changes can reduce frustration among blacks. Our analysis of local surveys and U.S. Census data shows that African Americans are generally less happy than whites with the performance of their city governments. But those same surveys show that when local governments spend more on social welfare and hire more African Americans, black dissatisfaction declines and blacks are as happy as whites with local government.

In most cities, a simple municipal ordinance would suffice to change local electoral laws. A survey in California found that more than 40% of cities had made a change in the timing of municipal elections in recent years. States can also get involved. In 2012, Arizona passed legislation mandating that many of its cities hold local elections that coincide with statewide contests. Citizens can also contribute. In states with direct democracy, they could put local election timing, district elections or other reforms on the statewide or local ballot.

Entrenched officeholders would probably resist such reforms. But the changes would be too powerful to be ignored. With a few small measures, we could do much to prevent future Fergusons from erupting across the country.

Zoltan Hajnal is a professor of political science at UC San Diego and the author of “America’s Uneven Democracy: Race, Turnout and Representation in City Politics.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.