Column: Are Republicans extinct in L.A.?

The scene at Mayor Eric Garcetti’s minimum-wage announcement on Labor Day was telling in a way that had little to do with his proposal. Joining him on the podium were the head of Los Angeles’ labor federation, the city’s preeminent businessman and philanthropist, and seven members of the City Council. These are people who have been known to disagree on some issues, but they have one thing in common: All are Democrats.

The decline of the Republican Party in California is a much-discussed phenomenon — the same state that elected Earl Warren to three terms and Ronald Reagan to two now does not have a single statewide officeholder who is a Republican — but its collapse in Los Angeles is even more pronounced. Of the several dozen city, county, state and federal elected officials who live within the Los Angeles city limits, only one is a Republican: City Councilman Mitchell Englander, who represents the northwest San Fernando Valley.

There are a couple of other Republicans who represent sections of the city, even though they don’t live in it, including L.A. County Supervisor Michael D. Antonovich, who lives in Glendale, and Rep. Howard “Buck” McKeon, who lives in Santa Clarita. McKeon has announced that he won’t seek reelection in the fall, and Antonovich, who has represented his district since 1980, will be termed out in two years.

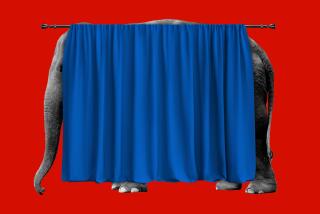

“I’m not just an endangered species,” Englander laughed as we discussed his lonely position. “I’m extinct.”

That said, he is hardly shunned at City Hall; to the contrary, he’s a cheerful participant in most council conversations. As he notes, every motion he introduces that gets a second is, by definition, an act of bipartisanship.

But even liberals and Democrats should be concerned about this region’s slide into a one-party state. Debates that rage elsewhere — over gun rights or gay marriage or access to abortion, just to name a few — are barely matters for discussion in Los Angeles, where no Republican candidate for mayor has even made the runoff since Richard Riordan left office in 2001. Instead, campaigns tend to focus on whether the city wants a moderate Democrat or a liberal Democrat, whether labor’s support is a help or a hindrance, whether carbon emissions should be cut by a lot or a whole lot.

Like many other observers, Arnold Steinberg, a Republican political consultant who was instrumental in Riordan’s elections, sees local politics becoming smaller and more union-dominated, with labor represented “on both sides of the table,” as he puts it. Steinberg doubts that Riordan could win in Los Angeles today.

In part, the GOP did this to itself. Its demand for ideological purity has driven away California moderates and left the party gasping for breath as the electorate turns away. But the Democrats’ victory is not a triumph for democracy. Without Republicans in the political conversation, there’s no one to challenge Democratic political orthodoxy.

That’s why Englander is such an important voice at City Hall. He was a small-business owner before he got into politics, and that experience continues to help shape his economic vision. He dislikes, for instance, the city’s business tax, which he faults because it is collected based on gross receipts rather than net income, a system he feels punishes businesses that produce lots of revenue but operate at low margins. But his efforts to eliminate the tax haven’t gone far. Garcetti and council members have tinkered with it, but the tax survives despite a growing a consensus that it’s bad for jobs.

Englander regards himself as the council’s most determined fiscal conservative, and he makes a good case that he deserves the title. He’s championed more prudent budgeting practices and successfully pushed for a bigger city reserve fund. He is consistently skeptical of government regulation and has an intuitive alignment with law enforcement (he’s a reserve police officer). He has pushed for more efficient business practices at City Hall. Tellingly, if with a little affectation, Englander does not refer to those in his district as “constituents”; he calls them “customers,” and feels it’s his job as their representative to satisfy them.

Over the next few weeks, Los Angeles will — or should — vigorously debate the question of whether imposing a city minimum wage will help the poor or eliminate jobs, or both. It should carefully consider whether the negative effects of such a requirement outweigh the positives.

Englander is still sifting through those arguments. Sadly, many of his colleagues already have decided. That’s life in a one-party state.

Twitter: @newton_jim

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.