Taxpayers don’t know how many jobs PPP loans saved during the pandemic. No one counted

A year after Congress created the Paycheck Protection Program, taxpayers don’t know how many jobs were saved by the nearly $1 trillion in forgivable loans issued to businesses during the pandemic.

And economists and government watchdog groups say they probably never will — because the government didn’t count.

The PPP was pitched as a way to save millions of jobs threatened during the COVID-19 recession. But the Small Business Administration under President Trump — and now under President Biden — hasn’t tracked figures on jobs that were saved, despite a legal requirement to do so.

“No one will actually know except for the recipients whatever happened with the loan and with the jobs,” said Sean Moulton, senior policy analyst at the Project on Government Oversight, a watchdog group.

The SBA’s initial estimate of 50 million jobs “supported” by the PPP was quickly dismissed as wildly inaccurate. Treasury Department economists place the number closer to 19 million, while economists studying the program estimate it’s between 2 million and 5 million.

More than 8.7 million forgivable loans worth $961 billion have been made so far. And Biden just signed a two-month extension, allowing the SBA to accept applications for $79 billion in loans through May 31. SBA officials told Congress they expect the money to be exhausted by the end of April. (The Los Angeles Times announced last week that it had received a $10-million PPP loan.)

But now a program that was originally promoted as a way to save millions of American jobs appears to have done far more to help the businesses and their owners, early economic studies suggest.

Thousands of businesses, including some that received $10-million PPP loans, reported having preserved no jobs at all with the assistance, according to the SBA. In other cases, PPP recipients used the two or three months of payroll support to simply postpone layoffs. And the smallest businesses — the ones in most need of help to pay employees — often missed out on the program altogether.

Nearly 19 million Americans are collecting unemployment insurance benefits. Because almost half of American workers are employed by small businesses, knowing whether the program was successful could be key to understanding how long the country’s economic recovery will take.

When it launched in 2020, the PPP exhausted $349 billion in 13 days. It was quickly anointed one of the most successful pandemic relief programs — until questions arose about whether all recipients really needed the money and some high-profile names, like the Shake Shack hamburger chain and the Los Angeles Lakers, returned their loans.

Under the CARES Act, Congress required the SBA to collect and make public quarterly data from all businesses that received more than $150,000, including how many jobs were affected by the loan and the company’s estimated economic growth.

In April 2020, just days after the program began issuing loans, the Trump administration’s Office of Management and Budget instructed the agency not to ask loan recipients to report back on the estimated number of jobs created or retained.

The budget office said “centrally available economic data” would provide sufficient information to produce the report. Its memo did not say where those data would come from, how they would be verified or why the budget office did not want the businesses to provide the information.

The result was a mishmash of data. Some businesses voluntarily listed the employees that would be supported with the money; others declined. Dozens have said the data released by the SBA don’t accurately reflect their number of employees or what they listed on their applications.

In January, the agency’s inspector general emphasized in a report that reliable information on the number of jobs saved was not available because the SBA did not collect it.

“SBA officials and national leaders do not have enough information to make informed decisions or determine to what extent the PPP met national program objectives. Additionally, SBA cannot accurately report jobs retained by PPP borrowers,” the watchdog said.

A spokesperson for the Office of Management and Budget on Thursday wouldn’t say whether the Biden administration intends to reverse the Trump policy and begin collecting the data as Congress instructed.

SBA officials told Congress repeatedly last year that clearer jobs numbers would become available once businesses applied for loan forgiveness, a process that is ongoing. That application asks for the number of jobs supported by the loan. But it’s not likely to provide the answer.

Moulton said applications for forgiveness will provide only a snapshot of current conditions, not the five years of jobs data that Congress specifically asked for in the CARES Act to verify whether the loans kept people in their jobs in the long term. Employees who were paid using the loan could have been laid off as soon as the money ran out, he said.

The PPP’s focus on jobs shifted over the course of the year, as businesses fretted that it did no good to pay employees if they weren’t able to pay rent and stay afloat. That led to changes that allowed more money to be spent on nonpayroll expenses.

Initially, borrowers had to put at least 75% of their loans toward payroll in order to have them fully forgiven. But in June, Congress lowered that threshold to 60%, allowing businesses to spend more money on expenses like rent and giving them more time to spend it.

No one disputes that the program probably helped thousands of small businesses survive. The scope of how many closed and how many stayed open will become more obvious as tax filings and bankruptcy data become available in time, economists say.

The disparities arose because the loans were distributed on a first-come, first-served basis by big banks, researchers said.

Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.) said the change made by Congress was an attempt to give small businesses more flexibility to keep their doors open, which in turn would preserve jobs.

“If they close, those people have no place to go to work,” Shaheen said. “Keeping small businesses open is about jobs.”

The program was designed to help as many businesses as possible, with little evidence required from them as to whether they faced revenue loss because of the pandemic.

Especially in the early days of the program, much of the money went to businesses that hadn’t lost revenue, had other resources like lines of credit to tap, or faced little risk of laying off workers without the loan.

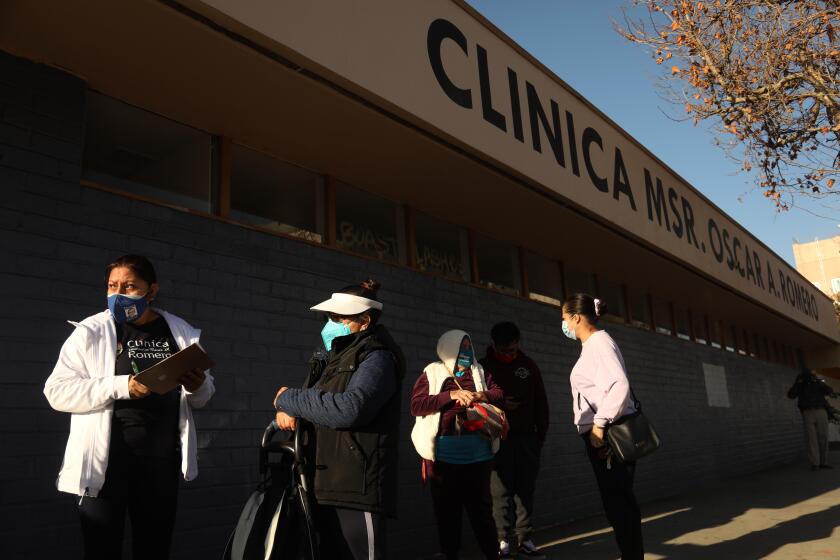

Microbusinesses, those with fewer than 10 employees, that would have benefited the most from the money were edged out of the first round by the bigger companies that had existing lending relationships with large banks.

Eric Zwick, an economist at the University of Chicago’s business school who has studied the program, said Congress could have modified the program in the early months of the pandemic after seeing how much money was going to businesses that weren’t in regions or industries facing economic peril because of shutdowns. Congress waited until December to prioritize loans for businesses with fewer employees and with major drops in revenue.

“You could have had the same program, just as [beneficial], possibly for half the price,” Zwick said.

UC Berkeley law professor Robert Bartlett, who surveyed businesses in Oakland during the pandemic, found that how much the loan contributed to a business’ expectation of survival depended largely on how many people it employed.

Microbusinesses of fewer than five employees needed their people to continue working in order to stay open and thus benefited the most from payroll support, Bartlett said. They were 20% more likely to say they expected to be open in six months because of the loan.

But for businesses with more than five employees, layoffs were the best way to manage cash flow, and they needed rent help from the government more than payroll support, Bartlett said. Though the PPP delayed layoffs for a few months, the businesses reported that the loans did not have a lasting effect on their ability to survive the next six months.

“One-size-fits-all programs might be politically expedient, but they may not be what all small businesses … need,” Bartlett said.

The program lapsed in August, but Congress in December approved a second round of loans, tightening eligibility requirements to focus support on the smallest, hardest-hit firms and those with the greatest drops in revenue. Only businesses with fewer than 300 employees could apply for a second loan, and money was set aside for particularly small and minority-owned businesses. It also created direct grants for performing venues and restaurants, which the SBA expects to make available this month.

Businesses applying for PPP loans still don’t have to report the number of jobs saved. Moulton, from the watchdog group, is urging the Biden administration to begin collecting such data and to retroactively require past recipients to report their figures, as a way to measure the program’s success.

“We are spending money right now on this program,” Moulton said. “It’s never too late to start getting this information.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.