To prevent Tommy John surgery, this app could prove apt

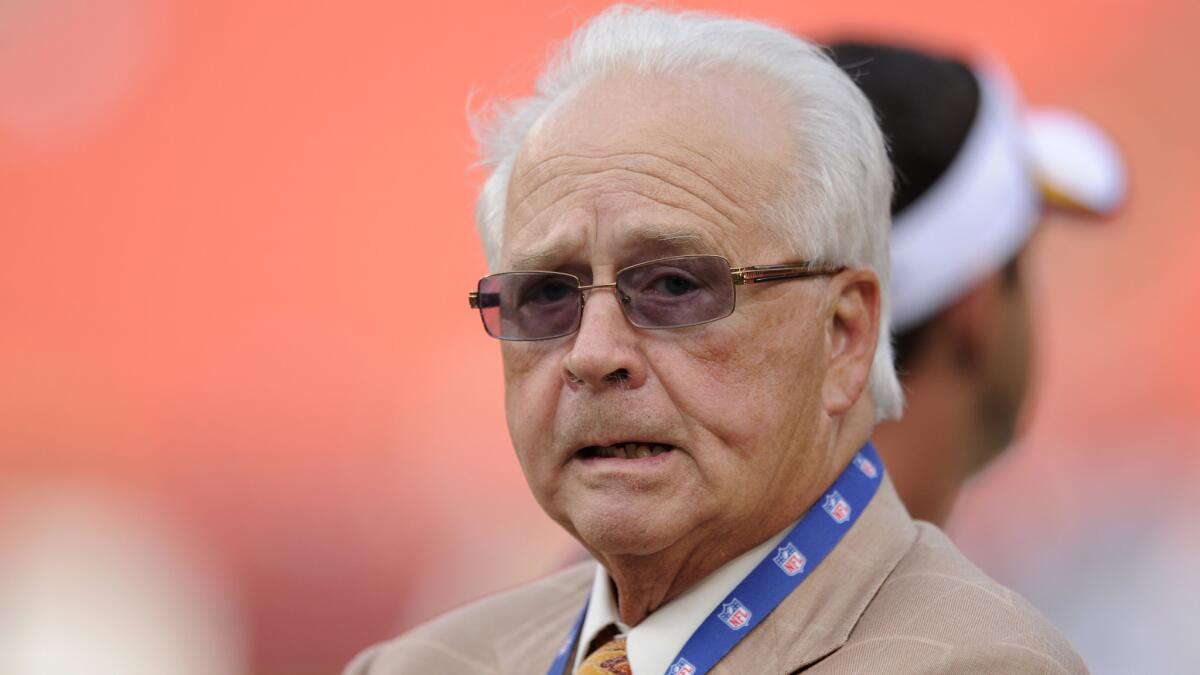

Dr. James Andrews is hoping that he can kill a good deal of his own business.

Andrews is a leading orthopedic surgeon, the man who many athletes — baseball pitchers in particular — turn to with career-threatening injuries.

One of his specialties is what is commonly known as Tommy John surgery, a procedure in which a damaged ligament in an elbow is replaced by a tendon from another part of the body.

Fifteen years ago, Andrews estimates he performed about 10 such procedures a year on young ballplayers with substantial injuries to their throwing arm, shoulder or elbow. That number is now tenfold.

His morning schedule earlier this week was typical: Four of the first five patients he saw at the Andrews Sports Medicine and Orthopedic Center in Birmingham, Ala., came in about Tommy John surgery; three of the four were high school students.

“It’s almost a crime to see that happen,” he said during a phone interview later in the day.

Andrews would be happier if he wasn’t so busy. For years, he says, he has been working to help athletes avoid the very injuries that have meant a boom to his business.

“And I still feel like I’m hitting my head against a wall,” he lamented.

He prefers to spend his time on preventive medicine, and his most recent efforts in that area have focused on “Throw Like a Pro,” an iOS application that became available Wednesday.

Throw Like a Pro is the inaugural product from Abracadabra Health, and according to Chief Executive Dewar Gaines, the first step in creating an all-encompassing rehabilitation and physical therapy application. An iOS exclusive, it costs $9.99, with a percentage of the proceeds going to the American Sports Medicine Institute, a nonprofit research foundation.

The app includes videos on proper throwing mechanics and suggested warmup routines, a tracker to monitor the pitches thrown in a game, and information prescribing the proper amount of rest between pitching sessions.

The information comes from Andrews and Kevin Wilk, a physical therapist who often works to rehabilitate Andrews’ patients. Together, they have more than 60 years of medical experience, and their knowledge is now as easy to access as Candy Crush.

Andrews estimates that about 60% of injuries in youth baseball are because of overuse — athletes throwing, playing or practicing too much.

That wasn’t as much of a problem when young athletes participated in a variety of sports. But with recent trends in sports specialization — baseball is now played year-round in many areas — the same muscles and joints are being tested without rest. Pitchers are especially vulnerable because throwing overhand isn’t a natural motion.

In some cases, monitoring rest can be further complicated because top players often compete on multiple teams. Each of those teams may be governed by rules for pitch counts and required rest, but since leagues and tournaments operate independently, it’s conceivable that a pitcher might throw for one team on Tuesday, another on Thursday and yet another on Sunday — and the coaches of each wouldn’t know about the other two.

The responsibility then falls close to home.

“Really, the key is the parents and players protecting themselves from doing too much,” said Stan Conte, vice president of medical services for the Dodgers. “Kevin Wilk and Dr. Andrews are both at the top of their field, so I sure as heck as a parent would listen to them.”

Wilk said the dangers of overuse can be found in a simple equation: “It’s pretty obvious that if you throw a lot, and you throw when you’re fatigued, and you throw hard all the time, and you don’t have recovery and don’t do exercises, you’re going to get hurt,” he said. “If you don’t get hurt, you’re in a really small minority.”

There is temptation, though, when players and parents are dreaming of a college scholarship or lucrative professional contract.

USC Coach Dan Hubbs said that when he first got into college coaching in 2000, he didn’t recruit players until after their junior year in high school. Now, USC and other prominent programs occasionally offer scholarships to players who haven’t even started high school.

“I honestly wish we didn’t recruit the way we do, but if we don’t, then they are all going to go somewhere else,” Hubbs said. “I’m uncomfortable with how young we go after kids now.”

Nick Pratto, a left-handed pitcher and outfielder, committed to Hubbs and USC last summer, before he attended his first high school class as a freshman at Santa Ana Mater Dei.

Pratto got on USC’s radar based on his performance in club baseball and for a USA age-group team. Pratto’s father, Jeff, coached in Little League and in club baseball and Nick never had an arm issue — until February.

Just weeks before the start of Mater Dei’s season, he experienced discomfort in his elbow. Nick was taken to a specialist, who found tightness but no sign of a significant injury.

Still, Nick took about three months off from pitching as he worked on improving his flexibility and strength. He returned as a pitcher to help push Mater Dei into a playoff spot.

“It was good that we caught it early,” Jeff Pratto said. “We can go down the line and name kid after kid after kid whose arm is not fit for pitching anymore because they were really trying to win that 10-year-old championship. There’s a lot of parents whose kids play who don’t really have an idea or awareness of it all.”

Those parents now have help in the form of an app.

Andrews and Wilk can only hope the information they provide will be sought, because both witness injuries every day that might have been avoided.

Last week, Wilk said, he had a patient in his clinic who had already undergone two elbow surgeries yet was still experiencing pain when he threw a baseball.

The patient was 12 years old.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.