Health insurers take on Big Pharma, plan to manufacture their own drugs

A group of leading U.S. health insurers, frustrated by the high cost of prescription drugs, plan to start manufacturing versions of popular generic medications, hoping the competition with pharmaceutical companies will bring down costs.

The move — the latest salvo in the escalating battle to control drug prices — highlights the failure of the Trump administration and Congress to deliver relief for millions of Americans struggling to afford their medications.

The announcement also comes as the state of California is exploring its own drug manufacturing plan.

Neither effort would affect the high price of branded pharmaceuticals, which is the largest driver of U.S. drug spending.

But the move could pressure drugmakers to rein in prices, particularly manufacturers that have dramatically hiked prices on products that have been on the market for years, even decades.

Leading the new effort is a consortium of 18 independent and locally owned Blue Cross and Blue Shield health plans, including Oakland-based Blue Shield of California, which is helping to spearhead the $55-million effort.

“Our core challenge is making our product affordable, and one of the biggest barriers to that is getting pharmaceuticals to be affordable,” said Blue Shield of California Chief Executive Paul Markovich. “We don’t see the status quo getting us there.”

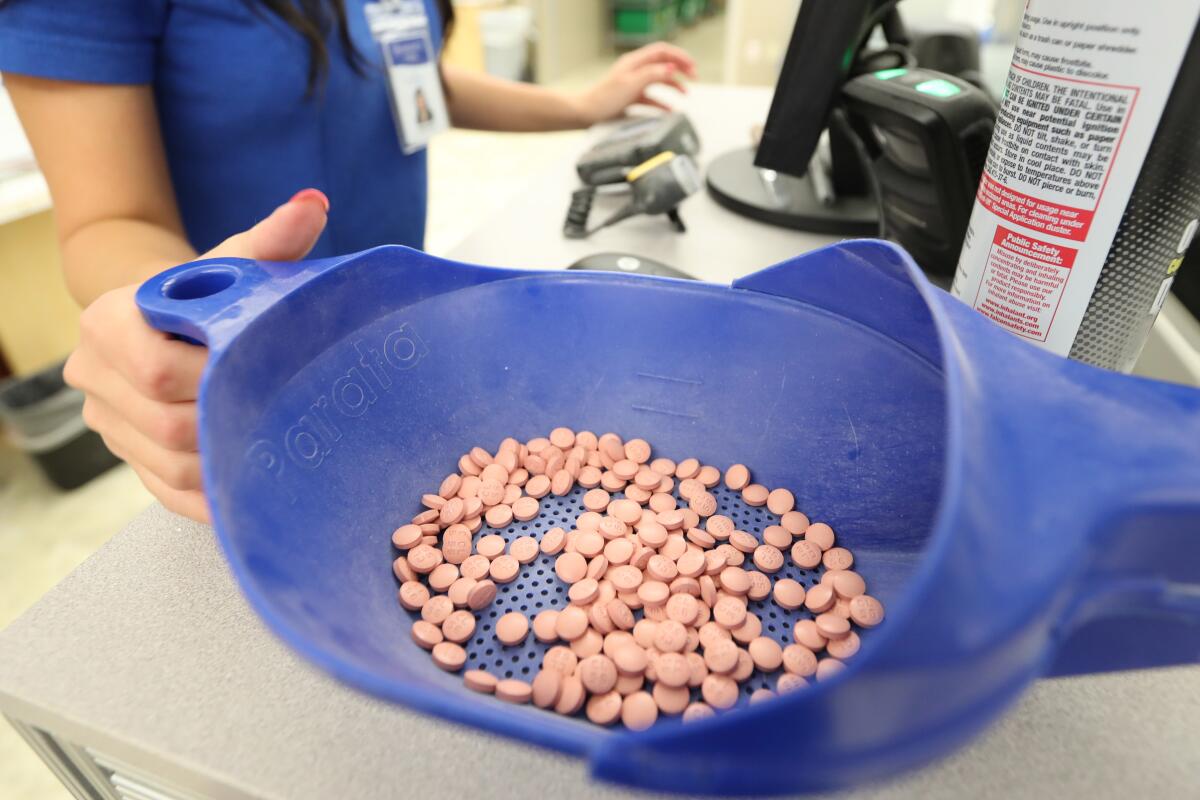

The Blue plans have not disclosed which drugs they will manufacture. But officials said the list would include generic medications widely used by patients with common chronic illnesses such as diabetes, multiple sclerosis and some mental health conditions.

The insurers — which cover about 40 million people — hope to make the first lower-priced drugs available to patients by early 2022.

They are working with Civica Rx, a Utah-based nonprofit. It was founded two years ago with a group of U.S. hospital systems to manufacture lower-cost medications that were frequently subject to shortages or exorbitant pricing.

Civica already has 18 medications in production, according to the company.

That partnership may bring real relief to some Americans, said Ben Wakana, executive director of Patients for Affordable Drugs, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy organization.

“Drug corporations are ripping people off, and anyone who wants to compete with them deserves credit,” he said.

He said the new initiative is unlikely to transform the pharmaceutical market, however.

“We should be realistic about the impact of this news. It’s like putting a Band-Aid on a bullet hole,” Wakana said. “What we really need is for the federal government to start negotiating with drug companies for lower-priced brand-name drugs.”

Markovich acknowledged that much more needs to be done. “This is a first step, but just a first step,” he said.

Generic medicines, which manufacturers can produce after patents expire, are credited with helping control overall costs as they are frequently less expensive than the brand-name versions.

But they represent only a fraction of total drug spending in the U.S.

In 2018, for example, costly brand-name pharmaceuticals accounted for 79% of total drug spending by Blue Cross Blue Shield members in commercial health plans, according to an analysis by the insurers.

Nevertheless, the generic market has been plagued by problems, including predatory pricing and deals among prescription drug companies that delay introduction of lower-priced generics.

In 2015, Martin Shkreli, a former hedge fund manager, set off a firestorm after acquiring the rights to sell Deraprim, a decades-old drug used to treat parasitic diseases, and then raising the price from $13.50 a tablet to $750 a tablet.

Shkreli was hardly alone. Two years ago, drugmaker Mylan dramatically raised the price of its EpiPen, a widely used injectable used to treat severe allergic reactions, only to then offer a generic version that still cost several times more than the initial price of the drug.

“The market is not working,” said Dr. Kevin A. Schulman, a Stanford physician and economist who has researched pharmaceutical pricing and sits on Civica’s advisory board.

That’s one reason California Gov. Gavin Newsom this month proposed that the state begin manufacturing drugs. Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren is backing a similar strategy as part of her campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination.

The generic pharmaceutical industry has greeted these initiatives with skepticism, noting that most generic drugs remain relatively affordable.

Wednesday, officials with the Assn. for Accessible Medicines, a Washington, D.C.,-based industry trade group, questioned the ability of the new health plan initiative to deliver.

“It begs the question of what they are trying to fix,” association spokesman Allen Goldberg said.

America’s largest health insurers, including UnitedHealthcare and Anthem, are not participating in the new drug manufacturing venture.

Other wealthy countries in Europe, East Asia and elsewhere more aggressively control the cost of medications, either directly through government price-setting or indirectly through tightly regulated price negotiations.

That has protected patients in these countries from the cost burdens that now routinely overwhelm Americans.

For example, just 7% of Germans reported cost-related problems getting medical care in the last year, compared with a third of Americans, an international survey recently found.

With little to no price regulation in the U.S., insurers and pharmacy benefit companies each negotiate their own prices with drugmakers, all of which are generally secret, and then pass on costs to patients.

The rapid run-up in drug prices, along with skyrocketing deductibles in commercial health insurance plans over the last decade, is taking a rising toll on American patients.

At the same time, federal law prevents the mammoth government Medicare program — which covers more than 60 million elderly and disabled Americans — from negotiating with drugmakers for lower prices.

House Democrats last month passed sweeping legislation to tackle high prices and give Medicare the authority to negotiate for lower prices on up to 250 medications.

But the bill has been categorically rejected by the White House and Republican leaders in the Senate, and it remains unclear whether lawmakers will be able to reach a compromise on any major prescription drug legislation this year.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.