China proposes law giving Beijing more power to crack down on opposition in Hong Kong

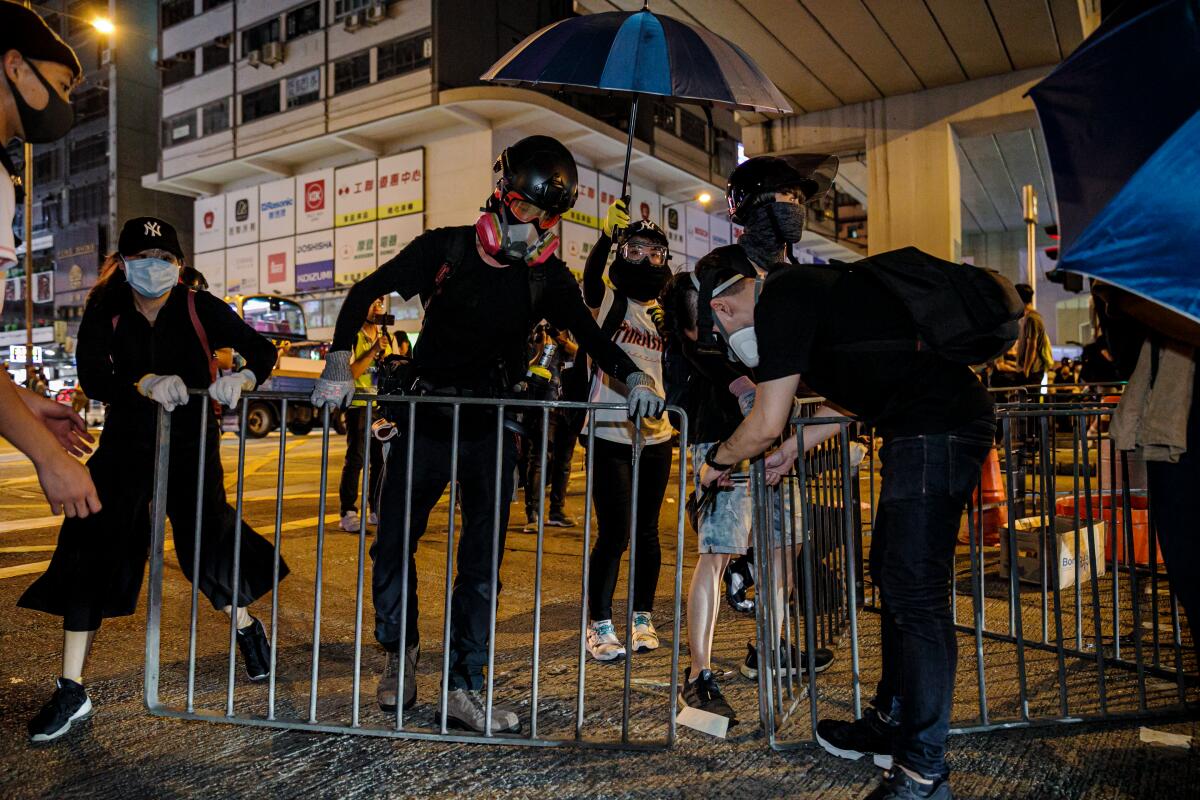

Those who watched Hong Kong’s protests escalate last year wondered week after week, as tear gas filled the streets and students screamed in the night, clashing with riot police, when the crackdown would come.

Demonstrators broke into the city’s legislative building, scrawling “It was you who taught me peaceful marches are useless.” They trampled on images of Communist Party leader Xi Jinping’s face and burned Chinese flags. They were besieged by police on a university campus for two weeks, their parents fearing a massacre.

But when the crackdown came Thursday, it did not erupt on the streets but in a staid news conference far away in the central government’s headquarters in Beijing. The latest and perhaps most powerful move yet to encroach on Hong Kong’s freedoms was delivered by a socially distanced man on a blue screen talking about Beijing’s plans to impose new national security laws on the former British colony.

“National security is the bedrock underpinning the stability of the country,” said Zhang Yesui, a spokesman for China’s National People’s Congress, at the opening of its annual meeting. “Safeguarding national security serves the fundamental interest of all Chinese, our Hong Kong compatriots included.”

The decision sent shock waves through Hong Kong, where past calls for national security legislation were shelved after mass protests. Many fear that new laws will suppress dissidents and further jeopardize civil liberties, destroying Hong Kong’s longtime status as a cultural and political refuge for those who would be persecuted in mainland China.

Zhang said the National People’s Congress, China’s rubber-stamp legislature, would exercise constitutional power to “establish and improve” a legal framework for enforcing national security in Hong Kong.

The strategy could bypass Hong Kong’s legislature by altering a part of the territory’s quasi-constitution without going through usual lawmaking process. Such direct intervention might compel the United States to declare as invalid “one country, two systems,” the understanding that Hong Kong should retain its semiautonomous status until 2047.

Such a prospect would further aggravate U.S.-China tensions, already at a breaking point over the COVID-19 pandemic, which the Trump administration blames on Beijing. The two sides’ testy exchanges over each other’s shortcomings in handling the disease have fueled talk of a new Cold War.

Zhang said China’s intentions in Hong Kong were “highly necessary” in light of “new circumstances,” alluding to more than six months of anti-government protests that rocked the special administrative region last year. Xi, China’s president, saw the uprising as a threat against the Communist Party and a test of his ability to rein in widening dissent.

What began as peaceful resistance last year to a bill that would have allowed extradition of suspected criminals to mainland China evolved into a citywide movement against police brutality and Beijing’s influence over the semiautonomous territory. More than 7,000 people were arrested for involvement with the protests, including children as young as 11.

Beijing regards the protests as U.S.-fomented separatism, a view made clear in a propaganda film titled “The Other Hong Kong” that state channel CCTV released Wednesday night.

Ominous music served as the backdrop to images of a burning city, with black-clad protesters throwing Molotov cocktails as police hunkered in defense.

The film repeatedly called protesters “violent, rioting criminals.” It accused the U.S. government of funding the demonstrations through democracy activists and independent media owners in Hong Kong, and claimed that protesters were naive youth being manipulated to destabilize China.

It is a view Beijing has promoted with great success at home — where there is little support for Hong Kong’s protests — but failed to push abroad. The protests drew global attention, challenging the Communist Party’s desired image of a wealthy nation of unified, thankful people, and disrupting the 70th anniversary celebration of the People’s Republic.

Now, with the world preoccupied by the coronavirus, Beijing is moving to assert control over Hong Kong’s institutions. Pro-Beijing lawmakers took over a committee on Monday by force, after security guards removed 15 opposition legislators from the chamber.

Local broadcaster RTHK was forced on Tuesday to suspend a program after it made jokes about the police. In the courts, the central government’s representatives in Hong Kong recently asserted their right to “supervise” the law.

Schools have also been targeted. Beijing officials are pushing to replace liberal studies, which taught critical thinking and which they blame for encouraging students to protest, with “patriotic education.”

Many Hong Kongers are looking to upcoming legislative elections in September to express their will, as they did in an overwhelming victory for pro-democratic candidates during district-level elections in November. But their choices may be limited. Hong Kong has begun arresting opposition lawmakers and activists who participated in last year’s protests.

What’s left is the streets, where Hong Kong’s police have been empowered to use force against protesters after a government report investigating officers’ conduct in last year’s protests recently vindicated the police. All five foreign experts hired to ensure objectivity in the report resigned in December over complaints of lack of independence.

The report by the Independent Police Complaints Council was widely criticized for failing to hold officers accountable for incidents including the night in July when law enforcement stood by while “triad” gang members stormed a subway station, beating protesters, journalists and bystanders with metal rods.

The report said there was “room for improvement” for the police, but described protesters’ behavior as “violence and vandalism verging on terrorism.”

Hong Kong’s police have also denied requests for gatherings, citing the need for social distancing due to the coronavirus. The city’s annual June 4 vigil, the only mass commemoration of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre in Beijing, has been barred.

Protests have begun and are likely to escalate.

This kind of direct lawmaking is “destruction” of Hong Kong’s Basic Law, said Johannes Chan, law professor at the University of Hong Kong, in an interview with local media. “It’s increasingly difficult to believe that ‘one country, two systems’ can still exist.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.