Glass is everywhere in blast-shattered Beirut, except where it’s supposed to be

Broken glass seems everywhere in this city.

It’s there in shiny, debris-filled mounds at the entrances to buildings. In single slivers lurking like spies in remote corners of apartments. In clumps that crunch underfoot in the street like freshly fallen snow reflecting the day’s last sunlight. A month after a gargantuan explosion ripped through Beirut on Aug. 4, people are still digging out glass shards from clothes, bedsheets, even skin.

The blast — caused by the detonation of a carelessly stored stockpile of 2,755 tons of ammonium nitrate in Beirut’s port — killed almost 200 people, injured thousands and pulverized whole neighborhoods. Its pressure wave hurtled for miles through the Lebanese capital, blowing out windowpanes in a citywide bloom of shattered glass.

Now, even as fragments lie all around them, Beirutis desperate to rebuild their homes and their lives are finding glass to be in short supply.

“We finished our stock on the fourth day after the explosion,” said Ahmad Ghoul, manager of his family-owned glass-cutting business. “And it’s not just us. Everyone is like this.”

It’s part of a wider shortage of materials crucial to the repair of the more than 87,000 homes affected by the blast, a task estimated to cost up to $4.6 billion, according to a damage assessment released last month by the World Bank.

In Lebanon, a country scarred by civil war and its role as a geopolitical pawn, the official explanation behind the Beirut explosion is just one of many.

And it couldn’t have come at a more difficult time, with the Lebanese already reeling like Job from a confluence of crises before the blast. The government, dysfunctional at the best of times, is all but paralyzed and has had three different prime ministers this year alone. For months, banks have refused to hand over money, forcing depositors into byzantine negotiations with tellers to get at their cash. Even when they succeed, it’s not worth much: The local currency has lost 80% of its value against the dollar, catapulting prices up in a country that imports 85% of its needs.

That includes glass for windowpanes, which has to be imported from countries such as Turkey or Egypt because no company in Lebanon has sufficient production capacity.

The available stock is hardly enough to cover the need. Economic instability since last year has given merchants little reason to replenish their stores.

The result has been widespread complaints of price-gouging across the supply chain, with residents in stricken areas, contractors and merchants complaining of importers demanding astronomical sums or insisting on being paid in hard-to-come-by dollars.

International assistance and aid groups have plugged some of the shortfall. Last week, Egypt’s ambassador met representatives of the Lebanese Ministry of Industry to hand over a donation of 125 tons of glass, local media reported. Algeria and others have followed suit.

Last month, the Lebanese government ordered a cap on the price for installing windows with aluminum siding and banned the use of dollars in transactions. It promised to subsidize glass imports and compensate residents for repairs.

But most vendors aren’t adhering to the cap, and few residents have faith that the army and police teams that have combed neighborhoods in recent weeks to survey damage will bring relief.

Los Angeles Times reporter Nabih Bulos was less than 500 yards from the center of the massive explosion in Beirut. He lived to tell the tale

In the east Beirut neighborhood of Karantina, one of the hardest-hit areas, volunteers sporting fluorescent-colored vests and hard hats clustered in front of a decrepit six-story building. Around them was a swirl of wood planks, aluminum bars, paint cans and the rhythmic patter of construction work.

“The biggest issue is to seal these places before the winter,” said Ali Kain, 35, a team leader and engineer working with Offrejoie, a Lebanon-based voluntary aid group. He said the craftsmen they had hired were working at “full power” to finish the job.

“There’s more demand for glass, so it’s harder. We’ve had donations from abroad, but they still haven’t arrived.… And September is when we can expect the rain to come.”

Many residents have limited repairs to only one window, or delayed them completely and made do with tarpaulin. On a nearby street corner, a coffee shop had installed a nylon sheet across the entrance.

Restoring historic districts badly damaged in the Beirut blast will be a tall order given Lebanon’s weak economy and developers’ eagerness to move in.

The shop’s front had been made entirely of glass. Had he been inside when the blast hit, said the manager, who gave only his first name, Basel, he probably would have been killed.

“The coffee machine flew across the room, right through where I would be sitting,” Basel said, pointing to a battered but heavy-looking espresso machine. Though he had cleaned the place, he can’t afford repairing the doors, forcing him to wait for one of the aid groups to help.

“We’ve had dozens of people come and measure the doorway, but nothing happened,” he said.

Some groups have called for broken and shattered glass to be repurposed and recycled. There’s certainly tons of it. On the main highway just outside Karantina last week, trucks laden with rubble lumbered toward Beirut’s posh waterfront district. They stopped in a parking lot near the ruins of a children’s theme park, pausing to pour their load onto a growing heap of urban viscera before moving out again.

News Alerts

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Much of that is unrecyclable, said Ziad Abi Chaker, an entrepreneur who owns Cedar Environmental, a waste management company.

“It’s not humanly possible to sort through this amount. And we don’t have the infrastructure to do mechanical sorting of rubble,” he said.

Instead, Abi Chaker has taken the lead in collecting relatively clean glass that fell inside homes and not in the streets. The loads, he said, are dispatched to glass factories to be melted down and used again. So far, almost 58 tons of glass have been hauled in, and Abi Chaker speculated that a further 40 tons would be collected.

This glass cannot be used to make windowpanes but can be refashioned into glassware, including jars, water jugs and water pipe bases, Abi Chaker said.

But using all of it would be difficult, said Hassan Koubaytari, manager of his family’s Golden Glass plant outside the northern city of Tripoli, one of three factories receiving Abi Chaker’s cargo.

“It’s an exceptional situation now. So we take what we can, but it’s not very much because a lot of the glass has impurities,” Koubaytari said.

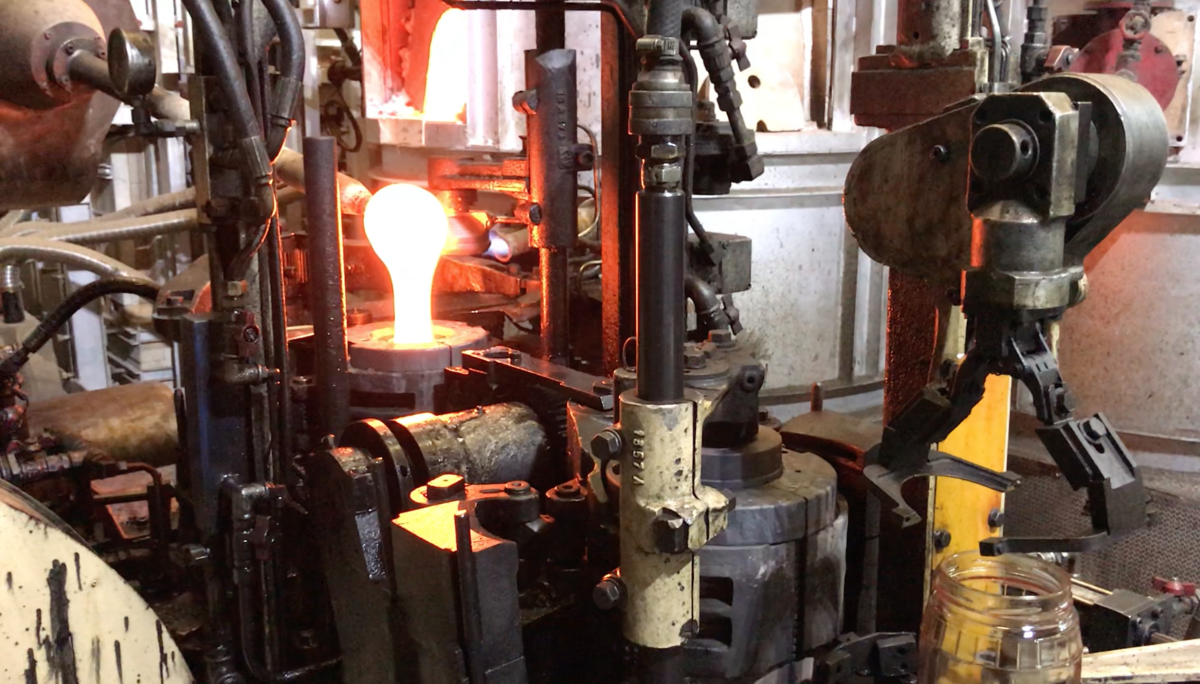

On the plant’s second floor, near a pile of burlap bags overflowing with rubble, two men sat on stools, armed with sieves. One by one, they scooped up a bucket full of rubble, dumped the contents onto the sieve and shook it out before picking out chunks of masonry and distressed-looking pieces of plastic. Leftover glass was cleaned, then taken away for further processing.

It was a Sisyphean but essential task, Koubaytari explained, warning of the dangers of impurities in the oven. Smaller pebbles, for example, could explode from the heat, while bigger ones would come out in the glassware and reduce its structural integrity. Mixing different types of glass — ones with gelatin or a mirror coating — would ruin the clarity. Most dangerous was iron, which could melt and damage the oven itself, stopping all production.

The beads that get used for glassware are the cheapest part of the process, worth just $8 a ton, Koubaytari said. That makes it difficult to justify recycling if materials aren’t properly sorted, and there’s been no initiative to subsidize the plant’s fuel costs, which are substantial.

“We’re not increasing our prices, but we can’t do this forever,” he said.

“We’ve spoken to the government, and we just need a bit of support, but we’ve gotten no response. They just don’t give a damn.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.