Double crisis in world’s poorest countries: COVID-19 surges meet vaccine shortages

Hati Maronjei once swore he would never get a COVID-19 shot, after a pastor warned that vaccines weren’t safe.

Now, four months after the first batch of vaccines arrived in Zimbabwe, the 44-year-old street hawker of electronic items is desperate for the shot he can’t get. Whenever he visits a clinic in the capital, Harare, he is told to try again the next day.

“I am getting frustrated and afraid,” he said. “I am always in crowded places, talking, selling to different people. I can’t lock myself in the house.”

A sense of dread is growing in some of the world’s poorest countries where coronavirus cases are surging and more contagious variants are taking hold but vaccine doses are in desperately short — or no — supply.

The crisis has alarmed public health officials along with the millions of unvaccinated, especially those who toil in the informal, off-the-books economy, live hand-to-mouth and pay cash in health emergencies. With intensive care units filling up in cities overwhelmed by the pandemic, severe disease can be a death sentence.

Africa is especially vulnerable. Its 1.3 billion people account for 18% of the world’s population, but the continent has received only 2% of all vaccine doses administered globally. And some African countries have yet to dispense a single shot.

The World Health Organization says the continent of 1.3 billion people is facing a severe shortage of vaccine as a new wave of infections is rising.

Health experts and world leaders have repeatedly warned that even if rich nations immunize all their people, the pandemic will not be defeated if the coronavirus is allowed to spread in countries starved of vaccine.

“We’ve said all through this pandemic that we are not safe unless we are all safe,” said John Nkengasong, a Cameroonian virologist who heads the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “We are only as strong as the weakest link.”

Zimbabwe, which has imposed new lockdown measures because of a sharp rise in deaths and cases, has used about two-thirds of its 1.7 million vaccine doses, for a population of 15 million. The government blames shortages in urban areas on logistical challenges.

Long lines form at centers such as Parirenyatwa Hospital, unlike months ago, when authorities were begging people to get vaccinated. Many are alarmed as the Southern Hemisphere winter sets in and the variant first identified in South Africa spreads in Harare, where young people crowd into betting houses, some with masks dangling from their chins and others without any face coverings at all.

Researchers in South Africa have documented an ominous development: the collision of the COVID-19 pandemic with HIV/AIDS.

“Most people are not wearing masks. There is no social distancing. The only answer is a vaccine, but I can’t get it,” Maronjei said.

At the start of the pandemic, many deeply impoverished countries with weak healthcare systems appeared to have avoided the worst. That is changing.

“The sobering trajectory of surging cases should rouse everyone to urgent action,” said Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, Africa director of the World Health Organization. “Public health measures must be scaled up fast to find, test, isolate and care for patients, and to quickly trace and isolate their contacts.”

New cases in Africa rose by nearly 30% in the past week, she said Thursday.

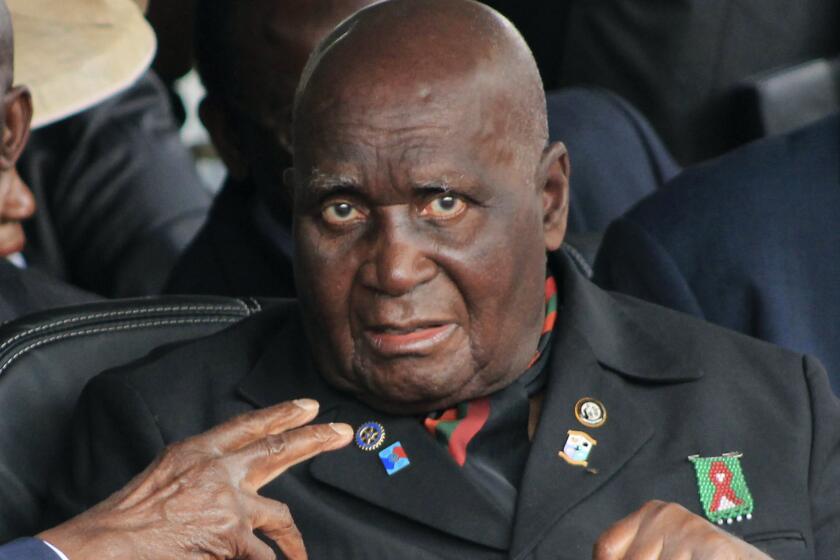

Zambia’s first president, Kenneth Kaunda, has died at 97.

In Zambia, where a vaccination campaign has stalled, authorities reported that the country is running out of bottled oxygen. Sick people whose symptoms are not severe are being turned away by hospitals in Lusaka, the capital.

“When we reached the hospital, we were told there was no bed space for her,” Jane Bwalya said of her 70-year-old grandmother. “They told us to manage the disease from home. So we just went back home, and we are trying to give her whatever medicine can reduce the symptoms.”

Uganda is likewise fighting a sharp rise in cases and is seeing an array of variants. Authorities report that the surge is infecting more people in their 20s and 30s.

Intensive care units in and around the capital, Kampala, are almost full, and Misaki Wayengera, a doctor who heads a committee advising Uganda’s government, said some patients are “praying for someone to pass on” so that they can get an ICU bed.

Pricing undermines Moscow’s claim that it is supplying poor countries with cheaper COVID-19 vaccines.

Many Ugandans feel hopeless when they see the astronomical medical bills of patients emerging from intensive care. Some have turned to concoctions of boiled herbs for protection. On social media, suggestions include lemongrass and small flowering plants. That has raised fears of poisoning.

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni imposed new restrictions this month that included closing all schools. But he avoided the extreme lockdown measures of last year, saying he didn’t want to hurt people’s livelihoods in a country with a vast informal sector.

For beauticians, restaurant workers and vendors in crowded open-air markets, the threat from the coronavirus may be high, but taking even a day off when sick is a hardship. Testing costs $22 to $65, prohibitive for the working class.

“Unless I am feeling very sick, I wouldn’t waste all my money to go and test for COVID,” said Aisha Mbabazi, a waiter in a restaurant just outside Kampala.

Dr. Ian Clarke, who founded a hospital in Uganda, said that while vaccine demand is growing among the previously hesitant, “the downside is that we do not know when, or from where, we will get the next batch” of shots.

Africa has recorded more than 5 million confirmed COVID-19 cases, including 135,000 deaths. That is a small fraction of the world’s caseload, but many fear the crisis could get much worse.

Nearly 90% of African countries are set to miss the global target of vaccinating 10% of their people by September, according to the World Health Organization.

One major problem is that COVAX, the U.N.-backed project to supply vaccine to poor corners of the world, is itself facing a serious shortage of vaccine.

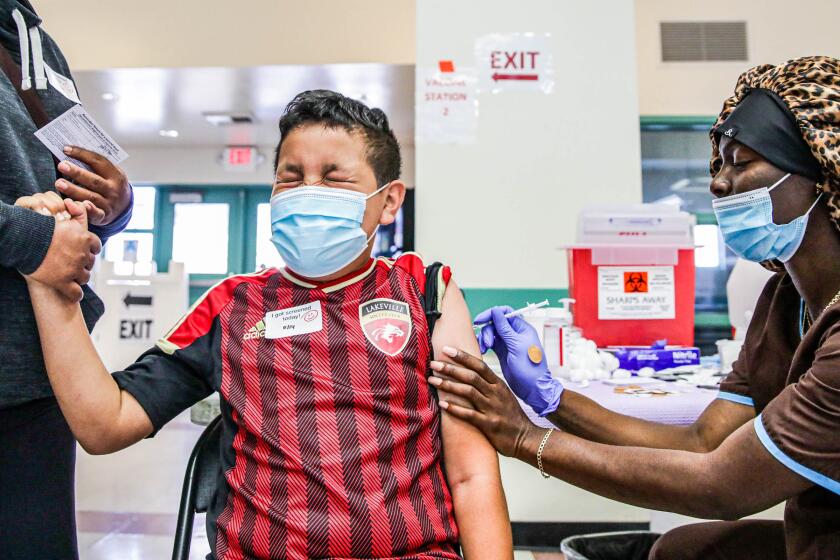

A growing contingent of medical experts is questioning the conventional wisdom that healthy children should get COVID-19 shots as soon as possible.

Amid a global outcry over the gap between the haves and the have-nots, the U.S., Britain and the other Group of 7 wealthy nations agreed last week to share at least 1 billion doses with struggling countries over the next year, with deliveries starting in August.

In the meantime, many of the world’s poor wait and worry.

In Afghanistan, where a surge threatens to overwhelm a war-battered health system, 700,000 doses donated by China arrived over the weekend, and within hours, “people were fighting with each other to get to the front of the line,” said Health Ministry spokesman Dr. Ghulam Dastigir Nazari.

The vaccine rush is notable in a country where many question the reality of the virus and rarely wear masks or social distance, often mocking those who do.

California officials announced the latest total, 40,098,803 doses of COVID-19 vaccine, Thursday afternoon.

At the end of May, about 600,000 Afghans had received at least one dose, or less than 2% of the population of 36 million. But the number of those doubly vaccinated is minute — “so few I couldn’t even say any percentage,” according to Nazari.

In Haiti, hospitals are turning away patients as the country awaits its first shipment of vaccines. A major delivery via COVAX was delayed amid government concern over side effects and a lack of infrastructure to keep the doses properly refrigerated.

“I’m at risk every single day,” said Nacheline Nazon, a 22-year-old salesperson who takes a colorful, crowded bus known as a tap-tap to work at a clothing store in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince, because that is all she can afford.

She said she wears a mask and washes her hands. If the vaccine becomes available, she said, “I’ll probably be the first one in line to get it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.