Where San Bernardino shooter Tashfeen Malik went to school to learn about Islam

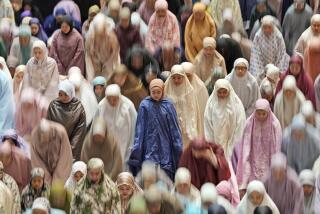

Pakistani students arrive Monday at Al Huda, a women-only seminary in Multan, Pakistan, where San Bernardino shooter Tashfeen Malik studied.

Her bespectacled face hidden behind a black veil, Farhat Hashmi’s voice is measured and confident as she mixes motherly advice about diet and child-rearing with solemn guidance about how to be a proper Muslim.

Hashmi, an Islamic scholar in her 50s, founded a network of religious schools that has educated thousands of mainly urban, upper-middle-class Pakistani women in a conservative strain of Islam. Recordings of Hashmi’s lectures, which have made their way to YouTube and iTunes, often show her speaking to classrooms filled with rapt young women eagerly scribbling notes.

Al Huda, Hashmi’s chain of schools, has more than 70 locations across Pakistan — including in the central city of Multan, where, for several months beginning in 2013, the students included the future San Bernardino shooter, Tashfeen Malik.

Last week’s rampage by Malik and her husband, Syed Rizwan Farook, which killed 14 and injured 21, has cast a fresh spotlight on the teachings of Al Huda, part of a vast patchwork of Islamic seminaries, Koran prayer groups and other religious institutions that operate outside Pakistani government control and are often accused of fueling radicalism.

Pakistani officials and experts who have studied Al Huda say this is the first time it has been linked to a militant attack, and an official with the organization said Monday that it “does not support terrorism.”

Yet experts say Al Huda seminaries promote anti-Western views and hard-line practices — including gender segregation and veils for women — that could encourage some adherents to lash out against nonbelievers.

“What happens in these Al Huda classes is teaching these urban, educated, upper-middle-class women a very conservative interpretation of Islam that makes them very judgmental about others around them — that it’s their job to go out and reform people and bring them toward the path of true Islam,” said Faiza Mushtaq, a Pakistani scholar who wrote her doctoral dissertation on the organization.

“Nothing that happens in the classroom explains the actions of this woman [Malik] but it can predispose people” to violence, Mushtaq said.

Malik and her husband both died in a shootout with police after the rampage at the nonprofit Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino.

The Times reported Sunday that Malik, 29, who was born to a well-off family in the Pakistani province of Punjab, attended classes at Al Huda while she was enrolled at a university in Multan. A woman who identified herself as director of Al Huda’s office in Multan confirmed Monday that Malik began a two-year course in religious studies in 2013 but left after “a few months” without earning a diploma.

“We had no contact with her afterwards,” said the official, who declined to give her name, citing a school policy.

However, the Associated Press cited a spokesperson for the school, Farrukh Chaudhry, as saying that Malik had studied there for slightly more than a year, from April 17, 2013, until May 3, 2014, when she handed in her last paper.

A statement on Hashmi’s personal website also confirmed that Malik had left Al Huda before finishing the program. “It seems that she was unable to understand the beautiful message of the Koran,” the statement said.

It said the organization denounced “extremism, violence and acts of terrorism,” adding that Muslims who understand the teachings of the religion would never commit such acts “because they will invoke the anger of Allah almighty and lead to harm and corruption on Earth.”

However, it said, “We cannot be held responsible for personal acts of any of our students.”

Al Huda, which means “guidance,” came to prominence over the last decade, attracting thousands of women to prayer groups and Koran classes in major Pakistani cities. Unlike most Pakistani religious madrassas that teach low-income, uneducated and mostly male pupils, Al Huda began by catering to the well-educated wives of military officers and businessmen — and was entirely driven by a woman.

Hashmi was active in the student wing of Jamaat-e-Islami, an Islamist political party that sought to establish sharia, or Islamic law, in Pakistan, before leaving to obtain a doctorate in Islamic studies from the University of Glasgow. She established the first Al Huda school in Islamabad in 1994 and soon opened branches in the cities of Karachi and Lahore.

She has characterized herself as a feminist, according to published reports, although she teaches that women should be obedient to their husbands and that, in some cases, men should have more than one wife.

Helped by donations from wealthy students and supporters, the schools have typically made tuition free or very cheap, while maintaining classes in the most affluent neighborhoods and using modern technologies, which now include apps and podcasts.

Experts say the classes helped ease women’s boredom, while the religious, all-female aspect made them socially acceptable. Mushtaq estimated that by 2010, more than 15,000 women had graduated from Al Huda courses, with many more attending classes or following online lectures without formally enrolling.

Al Huda and several other women’s seminaries in Pakistan have had a pronounced effect on urban life. Many more women in Islamabad and other cities now cover their hair, part of a trend toward religious conservatism that has been inspired by Sunni Muslim religious doctrine from Saudi Arabia.

The change was also epitomized by Malik, who family members in Pakistan said was a “modern girl” who was raised in Saudi Arabia and became much more conservative after returning to Pakistan for college in 2007.

Rubina Saigol, a Lahore-based researcher who has studied women’s seminaries, said Al Huda schools — and others like them — give women “a sense of belonging” even if the material being taught is far from progressive.

“The messages they were being given are extremely conservative and patriarchal — how to be an obedient wife, how a good Muslim woman should behave,” Saigol said. “It was not empowering except in the sense that it was a legitimate way for women to get out of the house and feel like they were part of a larger community through a religious activity instead of a coffee or tea party.”

Al Huda’s curriculum also appeared to promote conspiracy theories about the United States and other Western countries. Students that Saigol interviewed in Lahore several years ago refused to believe that Pakistani Taliban extremists were bombing girls’ schools and other civilian targets, instead blaming shadowy forces such as the CIA, Indian intelligence or Russia.

“While there is no direct teaching of violence, there is a sense that Muslims are under siege globally, with the attack on Iraq, the attack on Afghanistan, growing Islamophobia,” Saigol said. “The message is basically that America is the source of the trouble.”

Hashmi left Pakistan about a decade ago for Canada, where she keeps a low public profile and runs Al Huda’s office in Mississauga, a Toronto suburb, according to experts. The group also has offices in India, Britain and Hurst, Texas.

Although Hashmi has not advocated violence, she has promoted a specific interpretation of Sunni Islam that does not tolerate other Muslims and non-Muslims, who are sometimes referred to as nonbelievers walking a “path of sin,” said Sadaf Ahmad, anthropology professor at the Lahore University of Management Sciences.

“It is in this context that their beliefs have the potential to become dehumanizing, dangerous and harmful for others,” Ahmad said.

Although Pakistan has periodically promised to crack down on Islamic seminaries said to be promoting intolerance, clerics have pushed back against the authorities’ efforts. Pakistan has announced its own inquiry into the San Bernardino attack, but as of Monday, the official at Al Huda’s office in Multan said the group had not been contacted by investigators.

“We have nothing to hide and will cooperate with police and other security institutions if they contact us,” the official said.

Special correspondent Sahi reported from Islamabad and Times staff writer Bengali from Mumbai, India.

Twitter: @SBengali

MORE ON SAN BERNARDINO SHOOTING

Brown calls for stronger gun laws in wake of San Bernardino attack

San Bernardino County workers are back on the job days after shooting

FBI raids home of San Bernardino shooter’s friend, taking items in terrorist probe

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.