Crimean business owners caught up in pro-Russia officials’ crackdown

As Mila Selyamieva sees it, the bureaucratic brutality with which pro-Russia officials in Yalta moved to demolish restaurants, shops and hotels along the Black Sea helped kill her husband.

Selyamieva and Alexander Strekalin were among thousands of business owners ordered to give up property — in their case a waterfront restaurant — after Russia’s annexation of the Crimean peninsula in March 2014.

Strekalin, a 75-year-old ex-military officer and former deputy mayor of Yalta, vehemently resisted, even warning pro-Moscow officials that he would self-immolate to protest such government action.

“They told him, ‘Go, grandpa, do whatever you want,’” Selyamieva said recently during an interview near her apartment building in the Black Sea resort of 80,000. “All they wanted was to seize the beach for their own shady deals.”

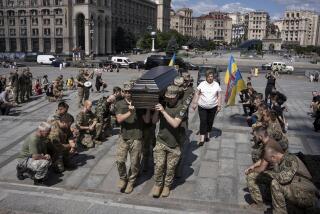

In September, Strekalin doused himself with acetone and flicked a lighter near the sunlit Primorsky beach, suffering fatal injuries. Hundreds of people showed up for his funeral, turning it into an impromptu protest against what many described as the result of Ukrainian and Russian corruption.

As part of Crimea’s transition to Russian legislation after the annexation, pro-Moscow authorities scrutinized property rights for each land lot, building and business, paralyzing or destroying hundreds of enterprises, according to activists and some officials.

Ukraine’s Justice Ministry announced in December 2014 that property held by at least 4,000 businesses and organizations in Crimea were seized by pro-Moscow officials and their proxies, who often fielded armed, masked men and brandished fake documents sanctioning the takeover.

Pro-Russia authorities said in 2015 they nationalized about 250 “strategic objects,” including a film studio, wineries, energy companies, natural gas fields, banks and telecommunications firms, transportation infrastructure and churches that belonged to the Ukrainian government, oligarchs, businessmen and religious groups.

The confiscated properties were privatized, authorities said, to compensate for the unspecified losses incurred by the disruption of the peninsula’s economic ties with Ukraine. One property, an oil storage facility near the city of Sevastopol, was returned to its Ukrainian owner in June after an unexpected court ruling.

To many residents, the expropriations resemble Russia in the 1990s, when mobsters and fledgling oligarchs strong-armed oil fields, businesses and real estate, or — to some extent — the brutal “nationalization” that followed the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

Denis Builov, a 36-year-old sailor from the Black Sea port of Sevastopol, said he had trouble obtaining foreign visas necessary for his travels and had to bypass bans on bank transfers to Crimea to withdraw his salary.

“Corruption is still there, but it’s gotten more complicated. It’s harder to reach an official you need,” Builov said in an interview.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has said Ukraine neglected Crimea for decades and has allocated more than $12 billion to build roads, schools, ports — and military bases. While the Kremlin is often criticized for Russia’s faltering economy and corruption, Putin has also warned Ukraine about venality within the government.

“I ask you to seriously energize your efforts to purge the halls of power of corrupt officials, of people who discredited themselves with doubtful connections,” Putin told security officials in August 2015 after sacking 60 Crimean officials, including five regional ministers.

In June, Sergei Aksyonov, the pro-Russia head of Crimea’s government, announced an upcoming “total demolition” of 6,000 waterfront restaurants, shops and hotels that were built without proper permits or that blocked access to public beaches. The “demolition list” was not made public, and several properties were razed at night — as was Strekalin’s restaurant, although his wife insists they had proper permits.

The announcement upset many in southern Crimea, a subtropical region popular for many years as a vacation spot. Many businesses have the required permits and licenses, but tens of thousands of Crimeans who also depend on tourists do not: They rent out rooms in their houses and their hotels and restaurants are often built and operated without permits and licenses.

“Many work here under black sails, including me,” Valentina, a 53-year-old who runs an unregistered cafe in her beach house outside Yalta, said in an interview, referring to tax-dodging businesses. “If they crack down on us, the bang [of public outcry] will be loud.”

Some property owners, activists and Ukrainian media say that regional leader Aksyonov and his inner circle are using the privatization and crackdown to expropriate Crimea’s most valuable assets.

Oleg Zubkov, the owner of private zoos and an outspoken supporter of the annexation, said that after he refused to share his profits with one of Aksyonov’s deputies, his businesses went through 150 court hearings and authorities ordered him to pay some $46,000 in fines.

Zubkov said every businessperson he knows suffers from venal pro-Moscow officials.

“I have not seen happy businessmen who are content with how things have been” after the annexation, he said in a phone interview.

Likewise, Vladimir Garnachuk, who briefly served as assistant to Crimea’s pro-Russia deputy prime minister in 2014, said in an interview in Moscow that the government is “plundering the peninsula like a war trophy.”

Garnachuk heads Clean Coast Crimea, a nonprofit that monitors the peninsula’s seaside. In a series of reports released after the annexation, the organization unveiled what it called multiple legal violations by development companies affiliated with Aksyonov, his relatives and business partners, including illegal construction in protected areas or on public property, use of undocumented workers and massive pollution.

Aksyonov did not respond to requests for comment.

A month after Strekalin’s death and the resulting public outcry, the Yalta City Council overturned the demolition order. The decision, however, has not eased his widow’s pain.

“He died for nothing,” Selyamieva said. “He died because of these animals.”

Mirovalev is a special correspondent.

ALSO

Russia begins to draw down its forces in Syria

Who, us? Kremlin says it doesn’t engage in ‘kompromat,’ but history suggests otherwise

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.