Celebrating 50 years of an unforgettable tale of the desert

Death Valley High School got a new bus driver in the fall of 1966. He was overqualified, with a master’s degree in philosophy from the University of New Mexico, and he was broke again. Edward Abbey had published a couple of novels to little notice, although his postmodern western “The Brave Cowboy” had been adapted into an interesting black-and-white movie with Kirk Douglas called “Lonely Are the Brave.”

Pushing 40 and owing child support, the wandering philosopher took whatever public-sector job he could get: seasonal park ranger, fire lookout, welfare case worker, school bus driver. Few remembered him, in Shoshone and Furnace Creek. He wasn’t there for long.

But in a corner of the saloon attached to the legal brothel at Ash Meadows, just across the Nevada line, the underemployed park ranger and philosopher worked on a new manuscript. His novels weren’t selling, and his agent in New York suggested something different. Maybe nonfiction, maybe some of Abbey’s barroom tales about camping.

Abbey had filled many notebooks during his 1950s summer jobs as the one-and-only on-site ranger at what was then called Arches National Monument, in the canyon country just north of Moab, Utah. It was an ideal life for a writer who needed the solitude and drama of a wild desert landscape. Sometimes he was there alone, living in a little plywood-and-tin housetrailer off a dirt road just north of Balanced Rock. Sometimes his wife and baby lived there with him. The book that was born from those journals, first published 50 years ago by McGraw Hill, made it clear that Edward Abbey preferred the time alone.

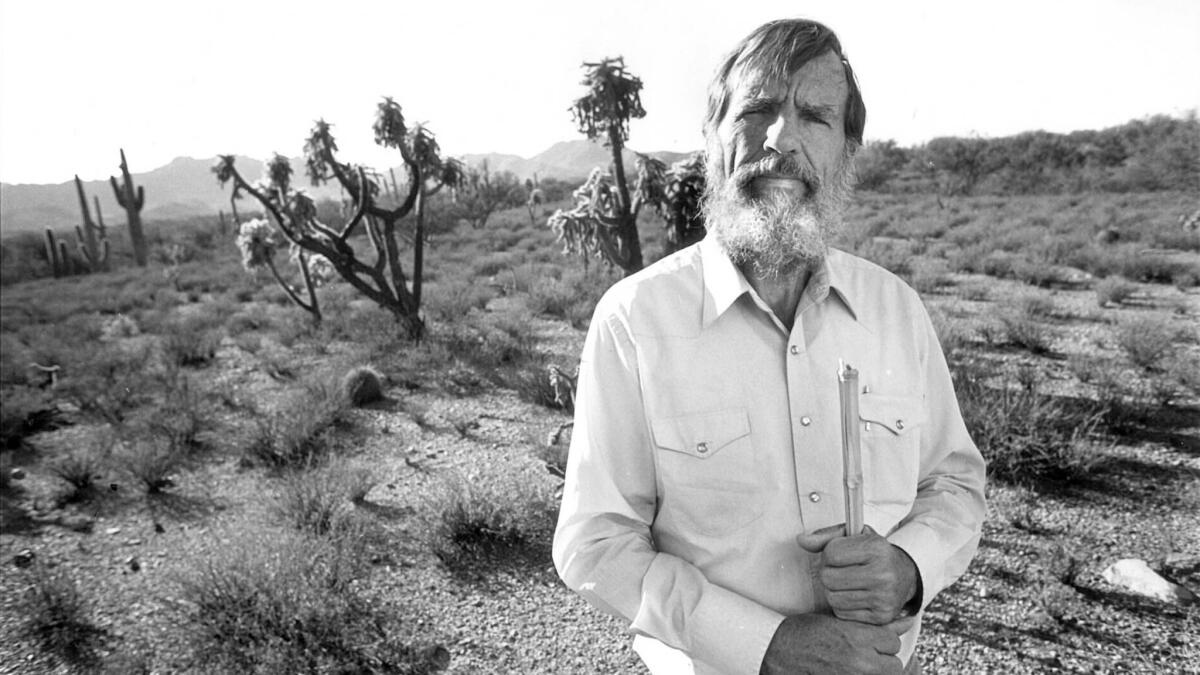

“Desert Solitaire,” published to little promotion and few sales in 1968, told the story of an American wanderer from Appalachian Pennsylvania finding his place in the remaining wild parts of the American West. It was good prose, plain and descriptive at times, comic or romantic when necessary. He was writing about the 1950s in the 1960s, and he was still formal enough to get approval from the East Coast elite: In the New York Times, Edwin Way Teale described the book as a “wild ride on a bucking bronco” and the author as “a rebel, an eloquent loner.”

There were stories of finding a dead tourist under a juniper tree, luring a moon-eyed horse from a canyon, guzzling near-beer with Mormon uranium miners at the Moab honky-tonk, and walking the lonesome trails of Arches when few visited this remote preserve at the end of a rutted dirt road. The stories and multiple seasons combine into one staggeringly beautiful high-desert summer in a landscape that demands contemplation. Why set aside natural places as wilderness, preserves, and national monuments? Why should the philosophical and aesthetic value of wild nature occasionally prevail over the corporate interests that see the landscape as opportunities for strip-mining and fracking?

Edward Abbey’s answers were strongly individualistic, perversely contradictory. A rattlesnake’s life was worth more than a man’s, he claims, and then he brains a bunny rabbit with a rock as an experiment in self-reliance. The park ranger feels horror and shame, watching the quivering bunny die. But then he feels the satisfaction of knowing he could live off the land, if he had to: “The experiment was a complete success. It will never be necessary to perform it again.” The ecology movement began in 1962 with Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring.” The pollution-belching factories, dead rivers, and open garbage dumps were finally seen as public dangers, and the sudden disappearance of wildlife — even the bald eagle was close to extinction! — shocked the nation into action. It was Richard Nixon’s administration, of all things, that would launch the Environmental Protection Agency, the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Air and Clean Water acts. to protect American citizens. But Abbey said we needed wilderness because we needed wilderness. His favorite example was that wilderness provided a haven for outlaws.

He claimed to be an anarchist, a man against the state, but his life’s work was dedicated to federal protection of desert wilderness. Three years after the first edition of “Desert Solitaire” came and went with its few encouraging reviews, the book was out of print and Edward Abbey was again making ends meet with seasonal fire-lookout and ranger work. That’s when the paperback edition appeared, and it was quickly embraced by hordes of long-haired backpackers filling the national parks of the Southwest. Abbey, a loner and extremist, spoke deeply to a communal movement made up of people young enough to be his children. A battered copy of “Desert Solitaire” in a backpack signified that the owner loved wilderness for the sake of wilderness, philosophical combat against the industrial capitalist state that had replaced citizens with consumers.

It was never a bestseller, but it was something nearly as good for a working writer: a steady seller. Robert Redford and Arizona Gov. Bruce Babbitt loved the book, befriended the author, spread its message in policy and culture. “Desert Solitaire” inspired action in its fans too. They demanded more protected wilderness, national parks for hikers and campers instead of traffic jams like the ones in Yosemite Valley then and Joshua Tree National Park today.

What to do about the traffic jams? To Abbey, it was simple: Ban automobiles in national parks. Get the rangers out of ticket booths and offices. “Make the bums range,” he wrote.

“Once we outlaw the motors and stop the road-building and force the multitudes back on their feet, the people will need leaders. A venturesome minority will always be eager to set off on their own, and no obstacles should be placed in their path; let them take risks, for Godsake, let them get lost, sunburnt, stranded, drowned, eaten by bears, buried alive under avalanches— that is the right and privilege of any free American. But the rest, the majority, most of them new to the out-of-doors, will need and welcome assistance, instruction and guidance.”

By the middle 1970s, Edward Abbey had fans of the rock-music variety, who showed up at his house, sent love letters, even found the lonely little fire-lookout towers where he now worked not so much out of necessity for money but for silence, privacy, inspiration, solitude. His journals, eventually published as “Confessions of a Barbarian,” reveal how much he desired real literary fame, the acceptance and love of the New York crowd he claimed to disdain, material riches so he could build a nice house somewhere in remote Utah or Arizona, stop worrying about child support and publishers turning down manuscripts. It never happened. The peculiar, shabby fame of Ed Abbey — “Cactus Ed” — meant that he was a working writer until the end, which came too quickly for Edward Abbey. (He died in 1989, age 62.)

The desert around Joshua Tree is fashionable now, and you always see Abbey’s half-century-old book on vacation-cabin bookshelves and in desert park gift shops. It is one of those books that can catch a reader on any page, with a rant against industrial tourism or a supernaturally tinged tale of wandering a canyon alone or a humorous remembrance of some misadventure. And just like that, you are converted. You are a desert lover, a desert defender, whether as a weekend pursuit or a full-time life. Protecting the wild desert becomes your moral priority. Desert conservation groups from Moab to the Mojave are made of “Desert Solitaire” readers, and most of them can tell you how it changed their lives, their work, how it focused and sharpened a mission they’d felt stirring but couldn’t yet articulate. “Desert Solitaire” gives us courage to act, and consoles us when our side — the moral side, the moral majority — loses a battle.

Fifty years after “Desert Solitaire,” you can look at a map of the Southwest and find ample evidence that things are now both worse and better. The people never quit coming west, feeding the monster sprawl of Salt Lake City and Las Vegas, Phoenix and Tucson, the Coachella Valley and the Antelope Valley. There is not nearly enough water for all these people, and thirsty cities are draining distant aquifers and rare desert springs in attempts to continue development, feed the cancer, forever extend the endless traffic-clogged boulevards of strip malls and tract homes and casino-hotels and golf courses. Species are still fading out, from loss of habitat and climate change. We face, of course, imminent extinction ourselves, whether by nuclear winter or endless summer.

Yet there are millions more acres of protected natural desert in California now, post-“Desert Solitaire,” and the connected parks and monuments from Death Valley down to Joshua Tree now make up the second-largest desert preserve on Earth. (The largest is Namib-Naukluft National Park, in southwest Africa.) But these preserves and parks are not really safe, not anymore. The Trump administration and its Interior Department, currently led by petroleum-industry lobbyists, is so hostile to America’s public lands and parks that it prompted a mass resignation from the 83-year-old National Park System Advisory Board — nine of 12 members resigned together in January.

California’s beloved new desert national monuments were immediately targeted by Trump’s secretary of the Interior, Ryan Zinke. It is Zinke who, between well-compensated pep talks to the oil industry and luxury travel at taxpayers’ expense, seeks to destroy California’s Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan, which saved millions of acres of wild desert from industrial development. Land conservationists have had the sudden realization that giving privately purchased land preserves to the American government for safekeeping is no longer wise.

The Nevada brothel where Abbey scribbled away his days is gone now, but the land where it stood serves as a pretty good memorial for “Desert Solitaire.” Ash Meadows, a rare desert wetland with 20 species of plant and animal found nowhere else on Earth, was saved in 1983 when it was purchased by the Nature Conservancy — more than 13,000 acres that were about to be converted into a housing development. It was given to the U.S. government, handed over in the belief that it would be protected forever — a woefully naive belief, when every acre of American public land is now threatened by the U.S. government itself.

For now, it’s this lush desert oasis fed by underground rivers is the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge. There’s an Abbey quote on the wall of the visitor center, by the restrooms.

Ken Layne is editor of “Desert Oracle” and host of its companion radio show and podcast. He lives in Joshua Tree.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.