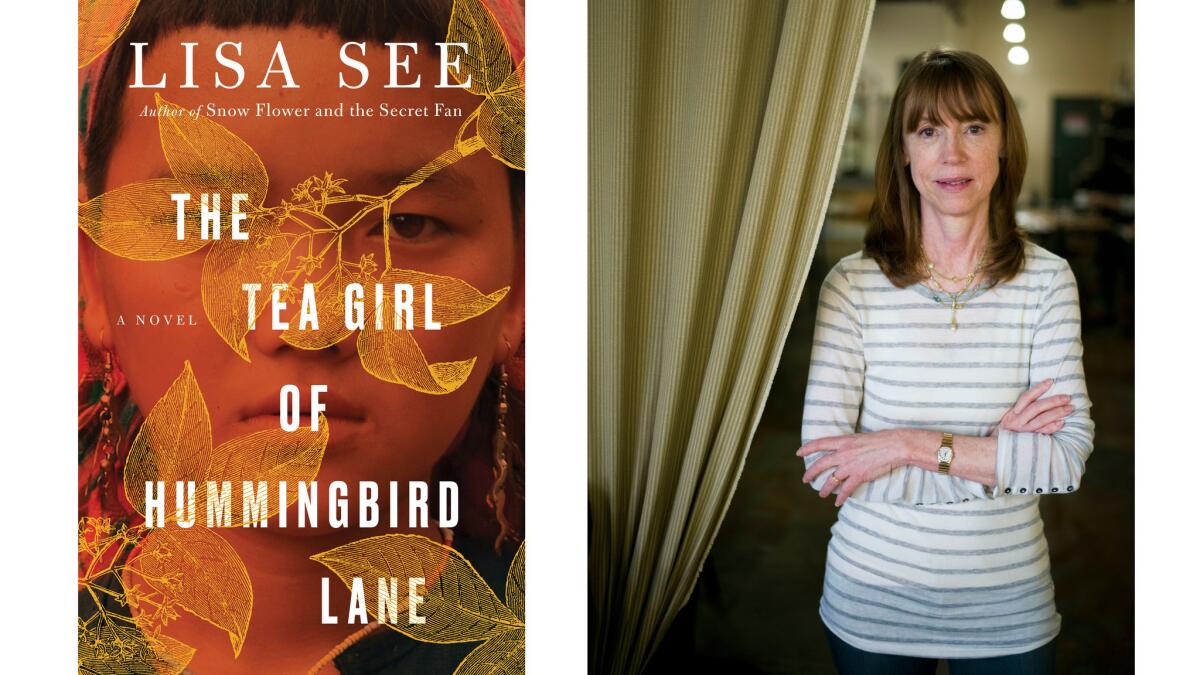

Read an excerpt of Lisa See’s ‘The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane’

In “The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane,” at No. 2 on the L.A. Times bestseller list, Lisa See tells the story of a mother in a remote Chinese village who must give up a child born out of wedlock, alongside the girl’s life after being adopted by an American couple. In this passage, Li-yan, from the Akha ethnic minority, brings her infant daughter to town.

I come to a tiny roadway that divides a block. It’s also unpaved but empty of people and bicycles. I creep into the shadows and sit shielded by a discarded cardboard box with my back against the wall. From here, I can watch the street without being seen. Surely those people will need to sleep. I eat some rice balls, ration my water, and feed Yan-yeh again. I tell her everything I can about Akha Law, about her a-ma and a-ba, about the lineage, and what it will mean to become a woman one day. How I will always love her. How I will think of her every breathing minute of my life. I whisper endearments into her face, and she looks up at me in that penetrating way of hers. Her tiny hand grips my forefinger, searing my heart and scarring it forever.

I’m awakened later — who knows how much time has passed? — by her mewling. I feel dawn coming in the quiet around me, but for now the night is still murky and dim. I must act now. Already tears pour from my eyes. I make sure her blanket is tight around her and the tea cake secure. I put her in the box. She doesn’t cry.

At the corner, I peer in both directions. To the left, in the distance, two women approach, sweeping the powdery dust from the surface of the dirt road with brooms made of long thatch — slowly from side to side, swish, swish, swish. I step out, turn right, and scuttle forward. I pass over two more streets, both deserted. All the while, I’m whispering, “Your a-ma loves you. I’ll never forget you.” I place the cardboard box on the steps of a building. No more words now. I must run, and I do — to the next corner, right, then right again, and to the next corner, so that I’ve returned to the edge of the main street. The two sweepers come closer — swish, swish, swish. I dart across the road and hide on that side so I can see the abandoned cardboard box. Its sides tremble. My daughter must be moving, realizing I’m gone. And then it comes — a terrible wail that cuts through the darkness.

The two sweepers look up from their work, cocking their ears like animals in the forest. And then another croaking shriek. The two women drop their brooms and come running. They don’t notice me, but I see them clearly — two elders with faces like rotten loquats. They drop to their knees on either side of the box. I hear them clucking, concerned yet comforting. One picks up the baby; the other scans the street. I can’t hear their conversation, but they’re decisive and knowing, as though they’ve encountered this situation before. Without hesitation, they begin marching back the way they came, back toward me. I slither farther into the shadows. When they pass me, I watch them until they reach their discarded brooms and continue on. I leave the safety of my hiding place and follow, creeping from doorway to doorway. They arrive at a building I passed earlier right on this same main road. The woman holding Yan-yeh sways and pats her back. The other woman bangs on the door. Lights come on. The door cracks open. A few words are exchanged. My baby is handed over, the door closed, and the two old women walk back to their brooms. The sign on the door reads: Menghai Social Welfare Institute.

I stay until the sun comes up. Grocers set baskets brimming with vegetables on the sidewalk. Barbers open their doors. Children walk hand in hand to school. The door to the Menghai Social Welfare Institute remains closed. I can’t stop crying, but there’s nothing more I can do. I begin my long walk back up Nannuo Mountain. I only get lost a few times. When I feel I can’t take another step, I venture into the forest. I fall asleep holding A-ma’s knife. The next day, by the time I reach my grove with the mother tree, where A-ma is waiting for me, I’m empty of tears. From now on, I cannot — I must not — let anyone see my sorrow. The loneliness of that … like I’m drowning …

See Lisa See at the L.A. Times Festival of Books at 11 a.m. Saturday on the panel “Everybody’s Got One: Fiction and Families.” And find her other appearances on her website.

Excerpted from “The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane.” © 2017 by Lisa See. Reprinted with permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster Inc.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.