How to solve a consumer ripoff by creating a new ripoff

Several weeks ago, Ticketmaster settled a long-running class action lawsuit over its ticket fees by agreeing to give aggrieved concertgoers a discount on future fees.

Paul Campos of the University of Colorado Law School subjects the agreement to close textual analysis to determine how all the parties make out from a deal being billed as a $400-million settlement. His findings:

Concertgoers get bupkis -- a $2.25 discount per future ticket, up to a maximum of 17 tickets per person, or a maximum of $38.25 per person.

The plaintiffs’ attorneys do great, receiving about $15 million in fees, plus costs up to another $1.5 million or so.

Ticketmaster does just fine; as Campos observes, it’s required to pay the discounts only to class members who buy more tickets from them in the future, thus turning the settlement agreement into a business opportunity.

Even UC Irvine’s law school gets a piece of the action -- a $3 million philanthropic grant from Ticketmaster for its consumer protection clinic.

According to the deal terms, Ticketmaster will be required to issue $386 million in “discount codes,” but it’s really on the hook for much less. If there are fewer claimants, the firm only has to make up the difference to a maximum of $42 million by issuing free tickets (to events of its own choosing). The class members are all those who purchased tickets from the firm between Oct. 21, 1999, and Feb. 27, 2013. Campos posits that a huge percentage of the class won’t claim their discounts, either because they won’t know about them or will consider them too trivial to care about.

It’s not as though Ticketmaster will be giving up real value. Whatever is claimed will come out of pure profit, because Ticketmaster’s fees are, to a great extent, profit; the firm, a unit of Live Nation, reported operating profit in 2012 of $295 million on revenue of $1.37 billion.

Indeed, Ticketmaster’s fees long have been a byword for exorbitance. For Justin Timberlake’s Thanksgiving week appearance at the Honda Center in Anaheim, for instance, the fee could add as much as 17% to a comparatively low-priced ticket ($16.35 on top of the $94 ticket). A handling fee often is tacked on that.

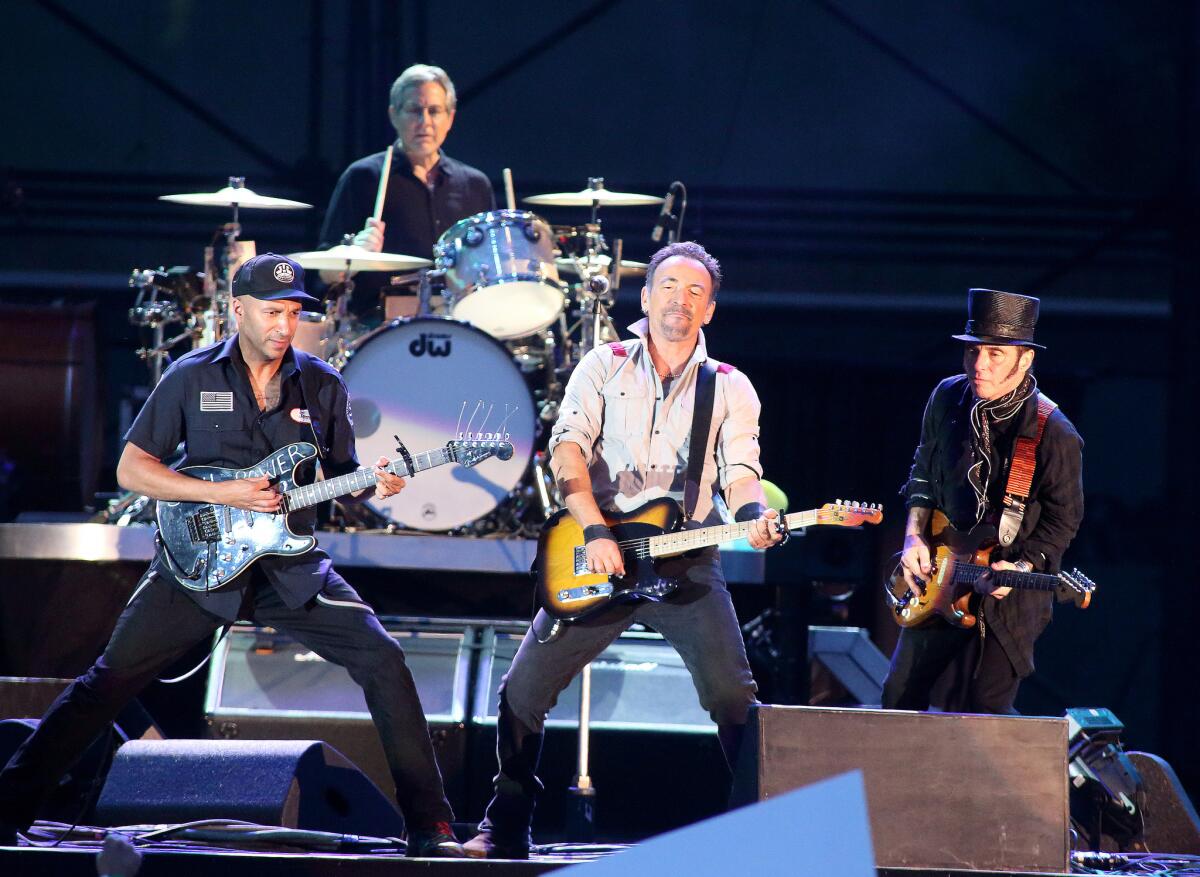

Plainly this is a company that needs to be watched like a hawk. In 2010 it was accused of pulling a fast one on Bruce Springsteen fans by claiming the Boss’ concerts were sold out and sending buyers to a related purchase website, where tickets were available at many times face value. This appeared to be a subterfuge to circumvent Springsteen’s demand that ticket prices be capped. The Federal Trade Commission ordered the firm to refund the overcharges.

The latest case illustrates all the flaws of consumer class action lawsuits. For one thing, it has been kicking around the Los Angeles Superior Court for an incredibly long time, having been filed 11 years ago. A final approval of the terms won’t come before early next year. It didn’t even originate as a complaint about the size of the fees, but rather over Ticketmaster’s practice of disguising its fees as passed-through service costs. These included a fee it assessed buyers to have their tickets delivered by UPS, which turned out to be rather more than UPS was charging Ticketmaster for the service -- in other words, a secret markup.

Campos observes that to the extent the availability of the discount prompts purchasers to buy tickets they might have otherwise passed up, the result is to fatten Ticketmaster’s profits. “In other words, the plaintiffs in this case are to a significant extent actually paying for the ‘damages’ they are putatively collecting.” This is how a smart company turns a loss into a profit, and how in so many of these ostensible consumer-protection lawsuits, the consumer gets mulcted again.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.