A media match plagued by a clash of cultures

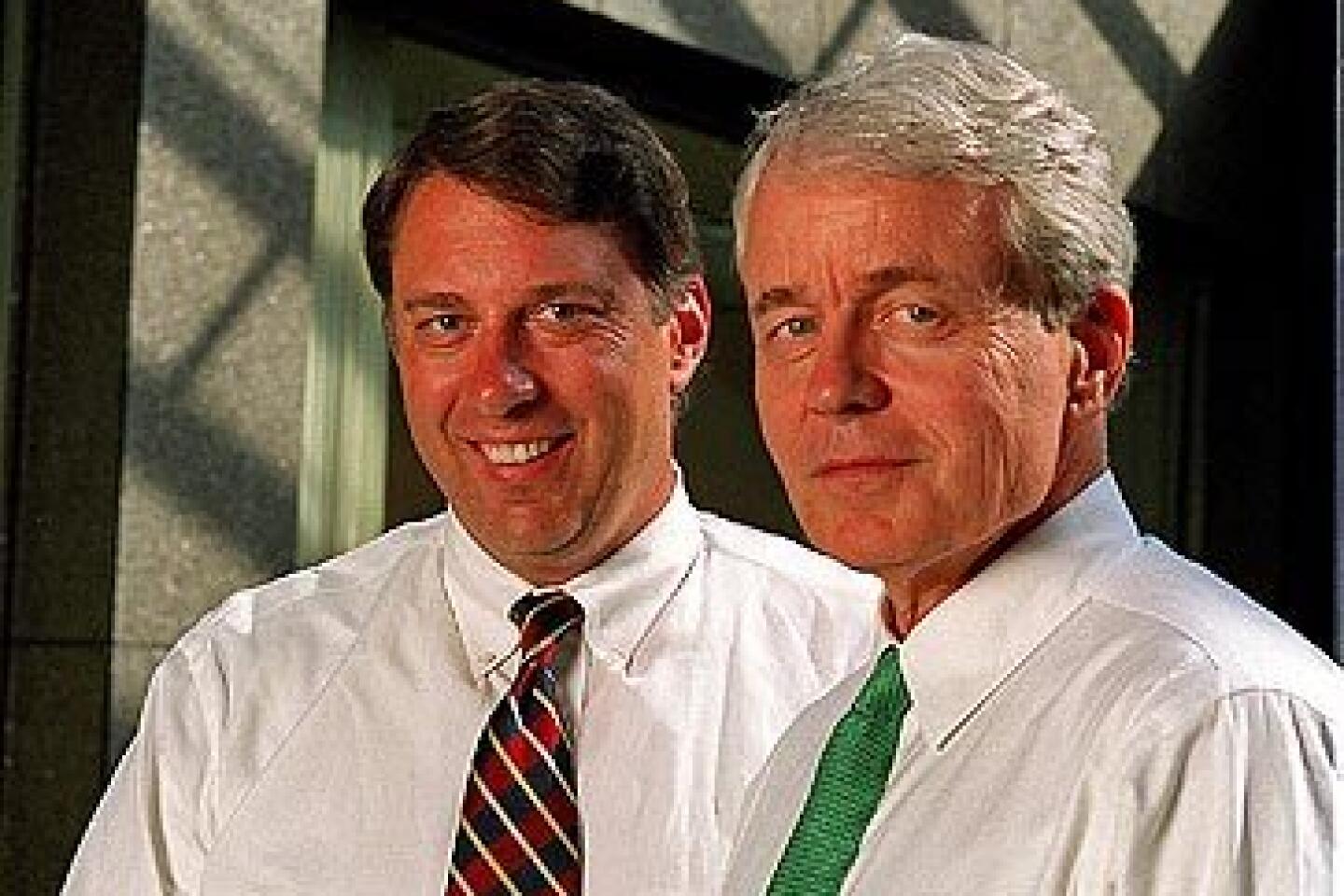

John S. Carroll was at the pinnacle of his career.

The editor of the Los Angeles Times had just led the newspaper to two Pulitzer Prizes, the 12th and 13th of his five-year tenure. The coveted public-service award that spring of 2005 seemed particularly sweet.

It honored the newspaper’s investigation into patient deaths at Martin Luther King Jr./Drew Medical Center — a series that Carroll had painstakingly polished himself, pencil in hand.

The public ebullience stood in stark contrast to Carroll’s private dismay. Hardly a month went by, it seemed to him, without a new demand from his Tribune Co. bosses in Chicago for staff reductions or for The Times to run more stories from other papers in the Tribune chain.

Before announcing his resignation in July of that year, Carroll contacted an old college friend, Norman Pearlstine, editor in chief at Time Inc., who helped arrange a meeting with Los Angeles’ preeminent power broker, Eli Broad.

In a weekend visit to Broad’s Brentwood home, Carroll told the billionaire philanthropist that he was likely to leave the paper and had a question to ask: Would Broad consider trying to buy the Los Angeles Times?

Carroll was stepping outside an editor’s traditional role as arms-length observer. And he was doing so without the knowledge of his employer, which had shown no inclination to sell the paper.

That meeting resonates loudly today: Broad joined investor Ron Burkle this week in a bid for all of Tribune, not just the Los Angeles Times. Another local magnate, David Geffen, is expected to counter with his own bid for the paper.

The Carroll-Broad meeting reflected a deteriorating relationship between Tribune and its largest newspaper, which would cost The Times two publishers and two editors in less than two years. Carroll’s departure followed that of Publisher John P. Puerner, whose replacement, Jeffrey M. Johnson, was shown the door last month. Carroll’s successor, Dean Baquet, ends his tenure today, after less than 16 months on the job.

The struggle has placed The Times on the front line in a battle sweeping the newspaper industry. Challenged by the Internet and other new media, corporate owners have demanded budget cuts to improve short-term financial performance. Journalists have pushed back, questioning whether public-company ownership can ever again be hospitable to the profession’s public-service aspirations.

“There is a revolution happening in our business,” said Nicholas Lemann, dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University. “There is a huge shift underway and no one knows how it’s going to play out . It’s a great drama, with great characters, that is just very sad.”

Tribune’s acquisition of Times Mirror Co. in 2000 brought together two dissimilar organizations in a union burdened from the start with high expectations. Tribune, a Midwestern company whose holdings included the Chicago Tribune, television stations and the Chicago Cubs baseball team, was known for its emphasis on efficiency and its early embrace of the Internet.

Times Mirror had long dominated the Southern California media landscape with The Times, for many years the biggest revenue producer of any American newspaper. With the ascension of Otis Chandler to the publisher’s office in 1960, The Times spent freely as it reached for journalistic excellence.

The combination of Tribune Co. and Times Mirror, it was hoped, would exploit multiple media platforms to capture larger audiences and more advertising dollars. It would have newspapers and TV stations in the nation’s three largest markets — New York, Los Angeles and Chicago. Its 22 television stations and satellite and cable television operations would reach 75% of U.S. television households.

So confident was Tribune that it paid one of the biggest premiums ever for a publicly traded company; the $8-billion purchase meant that the price of Times Mirror shares nearly doubled overnight.

But the promise of a go-go new century was deflated almost immediately. Only three months into the year 2000, the dot-com bubble burst. The 9/11 terrorist attacks the following year delivered another blow to the economy.

“As a result of those events, we were facing a revenue picture we did not anticipate when we bought Times Mirror,” recalled Puerner, the veteran Tribune executive brought in to be publisher of The Times.

The much-heralded synergy that had been the underpinning of the marriage proved elusive. The Times and its sister television station, KTLA-TV Channel 5, struggled to work together. The Times saw itself as a purveyor of serious journalism. KTLA attracted younger viewers, often with lighter fare and a breezier news style.

Among the many disconnects between the two: The newspaper used another TV station to sponsor the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, its most successful promotional event. And major investigations by The Times were not shared with KTLA in advance. The Times series last year on high school dropouts was featured on the local PBS affiliate, KCET.

A push to sell ads jointly in The Times and on KTLA faltered when the company stopped paying ad representatives commissions to promote sales.

The melding of Tribune newspapers also proved far from seamless. Carroll wanted to reserve as much space in The Times as possible for work by his own reporters and photographers. But the former editor said recently that he faced “a lot of pressure” to run stories from other Tribune papers.

“I believed top-tier papers were distinguished, in part, by producing nearly all of their own stories,” Carroll said. “You can buy a paper in any city in America full of wire-service copy. Running all this stuff from other Tribune papers was no different.”

Tribune Publishing President Scott C. Smith, who frequently clashed with Carroll and other Times executives, said the newspaper could only gain by making use of the geographic reach and expertise of other papers.

“I want to run the best story regardless of the source,” Smith said in an interview, “and that is different from what you hear from some editors, which is, ‘I want to run the story from my reporters whether it is the best story or not.’ ”

Tribune also had a tough time convincing large advertisers that they could make a “big city” buy through Tribune’s 11 daily newspapers. The company clearly had the dominant outlets in Los Angeles and Chicago, but its Newsday affiliate circulated primarily on Long Island, not in New York City, the market many advertisers demanded.

Advertising revenue stagnated, then declined. Between 2003 and 2005, Tribune’s operating profit fell 15%, to $1.15 billion, a trend that has accelerated recently.

Executives in Chicago had gained a reputation in the industry for running a tight ship. When revenue slipped, they expected expenditures to decrease. Head count at The Times dropped, to a current 2,800 employees from 5,300 six years earlier. Much of the reduction resulted from farming out circulation and other functions to outside contractors.

Promotional spending to advance The Times as a brand also withered, from $12.4 million the year Tribune took over to $89,000 in 2004. The paper will spend about $4 million this year on brand promotion.

Tribune’s Smith said that such spending could be an important factor but that The Times also needed to be concerned with “how engaged readers are in content.” Gerould Kern, the company’s vice president for editorial content, said, “Readers respond to exclusive, high-impact, locally relevant content.”

Journalists in Los Angeles believed such comments foreshadowed a diminution of foreign and national coverage. Tribune denied it.

Company executives questioned whether their counterparts in Los Angeles recognized that a structural shift in the newspaper business was causing a long-term decline in revenue. They believed a retrenchment was the only logical response.

Some journalists thought that such paring accelerated the slide.

“The excessive cuts on the business and promotion side were directly tied to circulation losses at the Los Angeles Times, which in turn were tied to ad and revenue losses,” said Carroll, who now teaches at Harvard University’s Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy. “Now the response to the downward spiral is further cuts in the newsroom.”

When it came to cutting the news staff, the discussion between Chicago and Los Angeles was inflamed by rivalry. The Times routinely turned up on lists of America’s best newspapers, while the Chicago Tribune was ranked a notch below.

Times executives would seethe when told their operations should be sized more like the Chicago paper’s. Some in Chicago thought their West Coast counterparts were more than a little haughty.

Although down from its high of about 1,200 before the Tribune takeover, The Times’ newsroom staff of 940 is still among the biggest in the industry. The Washington Post has about 760 editorial employees, while the staff of the New York Times, at about 1,200, is the biggest.

Still, even a loyal Tribune executive like Puerner was soon contending that The Times’ staff had a more complicated and ambitious agenda than did those at most papers. Carroll said the paper’s 18 foreign bureaus had particular appeal to the massive immigrant communities in Los Angeles. The publisher and editor told Chicago they needed larger business and features staffs, as well, to cover the nation’s entertainment capital.

An episode in the budget wars that Carroll found especially galling came in the spring of 2004.

The Times had just won five Pulitzer Prizes — its largest single haul ever and the second-greatest in the history of the prestigious awards.

As Times executives and honorees gathered in New York to collect the awards, Tribune received another round of disappointing advertising figures. Then-Tribune Publishing President Jack Fuller phoned Puerner the night before the ceremony to order more cuts.

Even if executives at The Times felt pressure from their Midwestern owner, they believed they had a kindred spirit in Fuller, a Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial writer and the author of five novels. Anxieties increased markedly when he stepped down at the start of 2005 and was replaced by Smith, a Northwestern University business-school graduate whom one Tribune executive described as “the smartest guy in the room.”

Times veteran Leo Wolinsky, a deputy managing editor under Carroll, told colleagues about an early meeting with Smith. He said Times editors described their desire to hire the best journalists possible, but Smith said that might not be necessary. Wolinsky worried that the paper might be forced to hire on the cheap. The dispute became public when Wolinsky was quoted in a New Yorker magazine article a year ago. Smith denied that he ever made such a statement.

Carroll continued to find hands-on editing and working with journalists invigorating. But by 2005, he found the financial pressures on the paper unrelenting, and, at 63, he had grown weary of the fight.

“The cutting became open-ended,” Carroll said. “And it was not accompanied by anything I could understand as a strategy for the future. It was just cutting to hit the numbers.”

Carroll declined to talk about what occurred next, but other sources described the events on condition of anonymity.

The editor called his old friend Pearlstine and said he was on the verge of quitting but held out hope that a civic-minded local buyer might purchase the paper from Tribune.

Pearlstine called Broad, another longtime friend. Broad — who had made a fortune in home building and then moved into financial services agreed to meet with Carroll.

At Broad’s hilltop Brentwood home, Carroll made it clear that he was interested in seeing Broad, and perhaps others, buy The Times.

The newspaperman told one associate that he had suggested to Broad that the paper might be put in the hands of a foundation modeled on the Poynter Institute, which runs a respected newspaper and a school for professional journalists in St. Petersburg, Fla.

Broad agreed to look into an acquisition, but obstacles became immediately apparent. Tribune had said it was not interested in selling, and even if it was, tax considerations could make the deal prohibitively costly.

Asked for comment on Carroll’s overture to Broad, Tribune’s Smith said: “All I would say is John Carroll is part of the past, not part of the future.”

On July 20, 2005, roughly two months after his meeting with Broad, Carroll announced he would leave The Times.

Managing Editor Dean Baquet considered following his boss out the door. Baquet, a New Orleans native, had won a Pulitzer Prize as a young reporter at the Chicago Tribune and went on to become national editor of the New York Times before Carroll lured him to Los Angeles.

Carroll told his protege, then 48, that he should stay on and fight to preserve the paper’s resources and quality. Baquet said he was willing to do so only after intensive discussions with Smith, who convinced him that there would be at least some relief from the downsizing.

Financial troubles continued to roil the industry. In the fall of 2005, newspapers in San Jose, New York, Boston and Philadelphia laid off hundreds of staffers, and the Los Angeles Times lost 85 positions, or 8% of its newsroom staff.

The activist group MoveOn.org protested cuts across the Tribune chain, presenting petitions with more than 17,000 signatures to Tribune management. The group said The Times’ “strong watchdog journalism” could be threatened.

By the fall of 2005, Tribune’s stock price had fallen so steeply that the combined company was worth $8 billion, about what Tribune had paid for Times Mirror.

In September of that year, Geffen approached Tribune Chief Executive Dennis J. FitzSimons to say he was interested in buying the newspaper. FitzSimons told Geffen that The Times was not for sale.

But the idea that The Times did not have to be yoked to Tribune provoked spirited discussion inside the newspaper. Some reporters and editors contended that the paper would be better off rolling the dice with a new master. Others recoiled at the idea, citing the foibles of Broad, Geffen and Burkle and the possibility of their meddling in news decisions.

Baquet, who in an interview declined to take a position on the desirability of local ownership, intently followed every report about the three billionaires, newsroom associates said. In the summer of 2006, Wolinsky, now one of two managing editors under Baquet, began to probe the billionaires’ interest and met privately with each of them.

Wolinsky, a Los Angeles native, USC graduate and mainstay of The Times for nearly three decades, said in an interview that he often met with prominent local figures to keep informed about developments that could affect the paper and the community.

He said he believed that he and other senior editors had been remiss in 2000, when they failed to ask enough questions about a special issue of the paper’s magazine featuring Staples Center. The Times’ reputation for objectivity was dealt a serious blow when it was revealed that the newspaper had shared revenue from the issue with the arena’s operators.

“I also felt as a newsroom leader that you have to help people who are worried about these things to understand what is going on,” Wolinsky said. “One of the things I learned, particularly from the Staples scandal, is you can’t wait until the end of the day and say, ‘I didn’t know.’ ”

Baquet said he had known of Wolinsky’s activities and believed they helped keep him and the newspaper abreast of important developments about Tribune and The Times.

In mid-June, Smith and FitzSimons visited the paper, trying to soothe nerves after the Chandler family of California, part of The Times’ founding dynasty and one of Tribune’s largest shareholders, had called for the sale of the company and publicly attacked management’s performance.

The session proved less than reassuring for both sides. In a meeting with top editors, the Chicago executives were asked whether the perception that Tribune hated the Los Angeles Times was valid. FitzSimons said such a feeling certainly was wrong. He said he and others running the company were well aware that their success was largely tied to the Los Angeles paper, which accounts for a fifth of Tribune’s profit.

By June, the misgivings inside the newspaper about Tribune burst into public, when columnist Steve Lopez wrote that “being purchased by someone with no experience and no earthly idea what he’s doing is quickly becoming more appealing.” A follow-up column invited the billionaires and others to consider buying The Times.

Meanwhile, people close to Broad said he continued to receive occasional phone calls from Carroll, encouraging local ownership of the paper.

In late August, as advertising revenue at The Times continued to slide, Smith’s budget lieutenants in Chicago demanded that Times business managers provide a list of proposed cutbacks.

Johnson, the publisher, told his subordinates not to deliver the information. When Smith arrived at The Times executive suite, Johnson held firm and the Tribune Publishing chief returned to Chicago empty-handed.

A few weeks later, in mid-September, the dispute reached a breaking point.

Baquet had met in late 2005 with a group of Los Angeles civic leaders, who demanded better local coverage by the paper. Now 20 of them released a letter to Tribune, contending that another round of staff reductions “could remove [The Times] from the top ranks of American journalism.”

The Times editor appeared buoyant when he got word that the local luminaries, including former Secretary of State Warren Christopher, were rallying around the paper.

In an interview about the letter, Baquet said he would oppose any substantial reductions in the paper’s editorial staff. Asked about Baquet’s position, Johnson backed his editor.

“Newspapers can’t cut their way into the future,” Johnson told The Times. “We have to carefully balance economic realities with serving our readers.”

The comments caused an uproar that brought national attention to the battle between Tribune and The Times.

Three weeks later, Smith flew to Los Angeles with three other Tribune executives and forced Johnson to resign. He was replaced by David D. Hiller, until then publisher of the Chicago Tribune.

Upon meeting the new publisher last month, Baquet quipped that he would soon have him “drinking the Kool-Aid” — adopting The Times’ position of sustaining a large and ambitious news staff. The new publisher and his editor agreed to seek common ground.

But three weeks later, Baquet said, he knew they were at an impasse over the extent of staff reductions. This week, Baquet said he had been asked to leave. Today is his last day.

On Monday, James E. O’Shea, managing editor of the Chicago Tribune, will become editor of The Times.

james.rainey@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.